Click on photo to start video.

Kizoo, part of the Forever Healthy Foundation, has announced today that it will be supporting biotech company LIfT Biosciences, a company that focuses on creating a new generation of cancer therapies that use our own immune systems.

Turning our immune system into a cancer-fighting machine

Led by CEO Alex Blyth, LIfT Biosciences is developing a new type of cancer immunotherapy approach that uses neutrophils, a type of immune cell, to seek and destroy all types of solid tumors.

WASHINGTON — Blue Origin filed a protest with the U.S. Government Accountability Office on Monday challenging the Air Force’s plan to select two providers in the next procurement of launch services under the National Security Space Launch program.

Blue Origin, a rocket manufacturer and suborbital spaceflight company founded by Jeff Bezos, filed what is known as a “pre-award” protest with the GAO, arguing that the rules set by the Air Force do not allow for a fair and open competition.

“The Air Force is pursuing a flawed acquisition strategy for the National Security Space Launch program,” states a Blue Origin fact sheet that outlines the reasons for the protest.

We are happy to announce our support for LIfT Biosciences. LIfT is developing the world’s first cell therapy to destroy all solid tumors, irrespective of strain or mutation.

The team lead by Alex Blyth is achieving this by building the world’s 1st cell bank of innately cancer-killing neutrophils. Congrats!

The scientists who came up with the theory of supergravity in the 1970s are $3 million richer.

The trio, physicists Sergio Ferrara, Daniel Z. Freedman and Peter van Nieuwenhuizen, won the Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, according to a statement Wednesday.

Supergravity is described in the prize announcement as a theory in which, “quantum variables are part of the description of the geometry of spacetime.”

The bottom line: The world as we know it — of complex global supply chains and countries playing to their best Ricardian advantage — is rapidly transforming into an atavistic place of trade barriers and bellicose rhetoric. If countries increasingly retreat into their nationalistic shells, no amount of fiscal or monetary stimulus will be able to head off the inevitable economic and financial consequences.

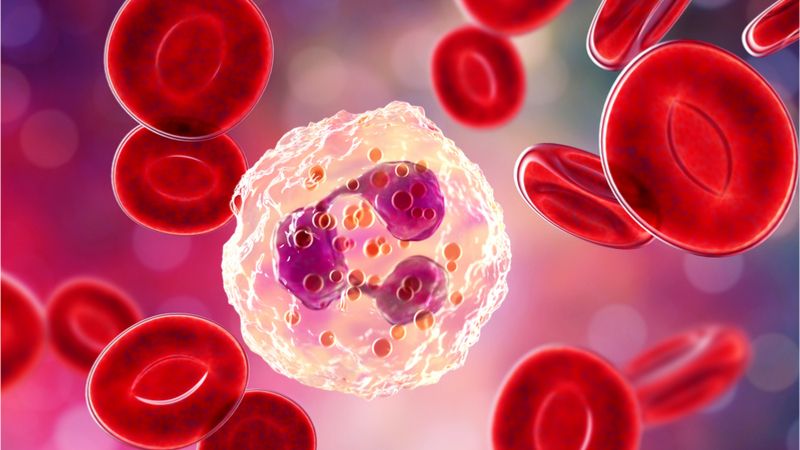

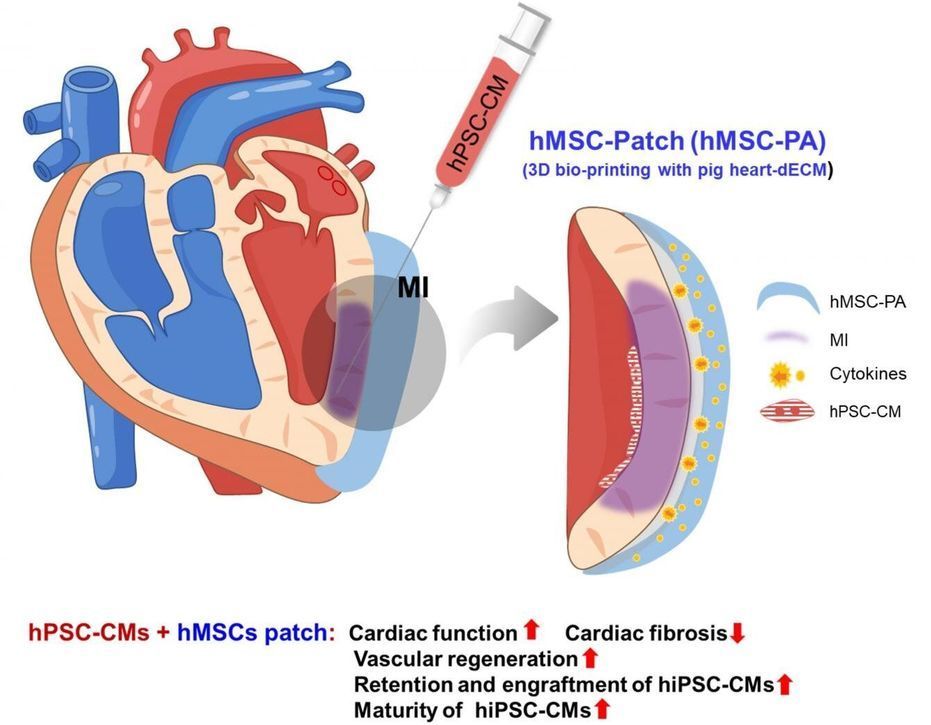

As a medical emergency caused by severe cardiovascular diseases, myocardial infarction (MI) can inflict permanent and life-threatening damage to the heart. A joint research team comprising scientists from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) has recently developed a multipronged approach for concurrently rejuvenating both the muscle cells and vascular systems of the heart by utilizing two types of stem cells. The findings give hope to develop a new treatment for repairing MI heart, as an alternative to the existing complex and risky heart transplant for seriously-ill patients.

MI is a fatal disorder caused by a shortage of coronary blood supply to the myocardium. It leads to permanent loss of heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes, CMs), and scar tissue formation, resulting in irreversible damage to cardiac function or even heart failure. With limited therapeutic options for severe MI and advanced heart failure, a heart transplant is the last resort. But it is very risky, costly and subject to limited suitable donors. Therefore, stem cell-based therapy has emerged as a promising therapeutic option.

Dr. Ban Kiwon, a stem cell biologist from Department of Biomedical Sciences at CityU, has been focusing on developing novel stem cell-based treatments for cardiac regeneration. “Heart is an organ composed of cardiac muscles and blood vessels, where vessels are essential to supply oxygen and energy to the muscles. Since both cardiac muscles and vasculatures would be severely damaged following MI, the therapeutic strategies should focus on comprehensive repair of both at the same time. But so far the strategies only focus on either one,” he explains.