As the number of electronics devices increases around the world, finding effective methods of recycling electronic waste (e-waste) is a growing concern. About 50 million tons of e-waste is generated each year and only 20% of that is recycled. Most of the remaining 80% ends up in a landfill where it can become an environmental problem. Currently, e-waste recycling involves mechanical crushers and chemical baths, which are expensive, and manual labor, which can cause significant health and environmental problems when not performed properly. Thus, researchers from Kumamoto University, Japan have been using pulsed power (pulsed electric discharges) to develop a cleaner and more efficient recycling method.

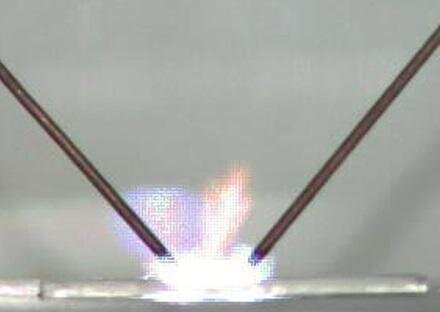

Pulsed power has been shown to be successful in processing various waste materials, from concrete to waste water. To test its ability to be used in e-waste recycling, researchers examined its effectiveness in separating components found in one of the most prolific types of e-waste, CD ROMs. In previous work, they showed that complete separation of metal from plastic occurred using 30 pulses at about 35 J/pulse (At the current price of electricity in Tokyo, this amount of energy costs about 0.4 Yen for recycling 100 CD ROMs). To examine the mechanism of material separation using this method, researchers performed further analyses by observing the plasma discharge with a high-speed camera, by taking schlieren visualizations to assess the shock wave, and using shadowgraph images to measure fragment motion.

Images at the early stage of electrical discharge showed two distinct light emissions: blue-white and orange. These indicated excitation of aluminum and upper protective plastic materials respectively. After the plasma dissipated, fragments of metal and plastic could be seen flying away from the CD ROM sample.