Children with autism were able to improve their social skills by using a smartphone app paired with Google Glass to help them understand the emotions conveyed in people’s facial expressions, according to a pilot study by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Prior to participating in the study, Alex, 9, found it overwhelming to look people in the eye. Gentle encouragement from his mother, Donji Cullenbine, hadn’t helped. “I would smile and say things like, ‘You looked at me three times today!’ But it didn’t really move the bar,” she said. Using Google Glass transformed how Alex felt about looking at faces, Cullenbine said. “It was a game environment in which he wanted to win — he wanted to guess right.”

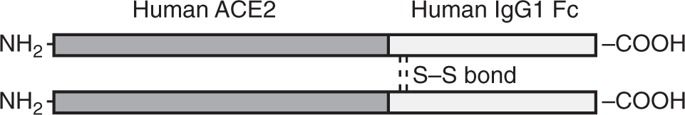

The therapy, described in findings published online Aug. 2 in npj Digital Medicine, uses a Stanford-designed app that provides real-time cues about other people’s facial expressions to a child wearing Google Glass. The device, which was linked with a smartphone through a local wireless network, consists of a glasses-like frame equipped with a camera to record the wearer’s field of view, as well as a small screen and a speaker to give the wearer visual and audio information. As the child interacts with others, the app identifies and names their emotions through the Google Glass speaker or screen. After one to three months of regular use, parents reported that children with autism made more eye contact and related better to others.