Category: transportation – Page 215

Elon Musk fans have created a $600,000 GOAT monument dedicated to their hero

Diehard Elon Musk fans have created a 30-foot-long monument dedicated to their hero – and it cost them over half a million pounds ($600,000).

The unique piece sees the richest man in the world’s head attached to a goat’s body while riding a rocket.

It’s the brainchild of cryptocurrency firm Elon GOAT Token ($EGT), who later this month plan to present it to the billionaire at his Tesla workplace in Austin, Texas.

Pilots Go Head to Head in “World’s First Electric Flying Car Race”

Flying car startup Airspeeder has completed what it’s referring to as the “world’s first electric flying car race” in the South Australian desert.

While the two competing pilots were steering the two full-scale flying cars remotely, it still made for an epic launch of a brand new kind of motorsport, as seen in a promotional video of the event.

“This is just the start, this first race offers only a glimpse of our promise to deliver the most progressive, transformative and exciting motorsport in the world,” Airspeeder founder Matt Pearson said in a press release.

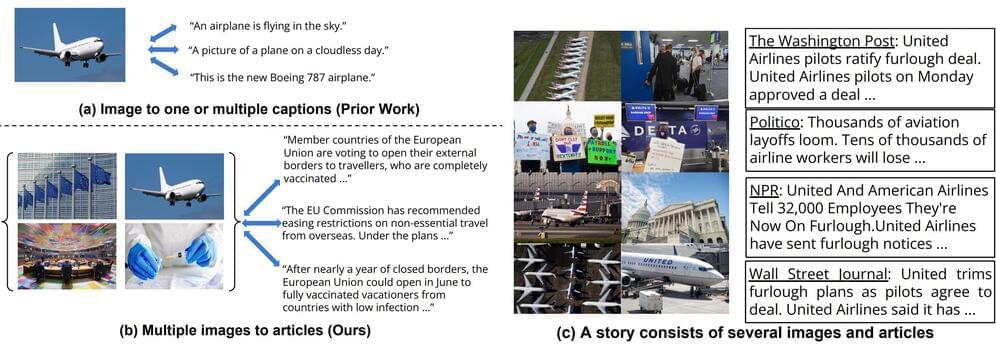

Boston University and Google Researchers Introduce An Artificial Intelligence (AI) Based Method To Illustrate Articles With Visual Summarizes

Recent progress in generative models has paved the way to a manifold of tasks that some years ago were only imaginable. With the help of large-scale image-text datasets, generative models can learn powerful representations exploited in fields such as text-to-image or image-to-text translation.

The recent release of Stable Diffusion and the DALL-E API led to great excitement around text-to-image generative models capable of generating complex and stunning novel images from an input descriptive text, similar to performing a search on the internet.

With the rising interest in the reverse task, i.e., image-to-text translation, several studies tried to generate captions from input images. These methods often presume a one-to-one correspondence between pictures and their captions. However, multiple images can be connected to and paired with a long text narrative, such as photos in a news article. Therefore, the need for illustrative correspondences (e.g., “travel” or “vacation”) rather than literal one-to-one captions (e.g., “airplane flying”).

Artificial Intelligence is the Magic Tool the World was Waiting For

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly changing the world. Emerging technologies on a daily basis in AI capabilities have lead to a number of innovations including autonomous vehicles, self-driving flights, robotics, etc. Some of the AI technologies feature predictions on future and accurate decision-making. AI is the best friend to technology leaders who want to make the world a better place with unfolding inventions.

Whether humans agree or not, AI developments are slowly impacting all aspects of the society including the economy. However, some technologies might even bring challenges and risks to the working environment. To keep a track on AI development, good leaders head the AI world to ensure trust, reliability, safety and accuracy.

Intelligent behaviour has long been considered a uniquely human attribute. But when computer science and IT networks started evolving, artificial intelligence and people who stood by them were on the spotlight. AI in today’s world is both developing and under control. Without a transformation here, AI will never fully deliver the problems and dilemmas of business only with data and algorithms. Wise leaders do not only create and capture vital economic values, rather build a more sustainable and legitimate organisation. Leaders in AI sectors have eyes to see AI decisions and ears to hear employees perspective.

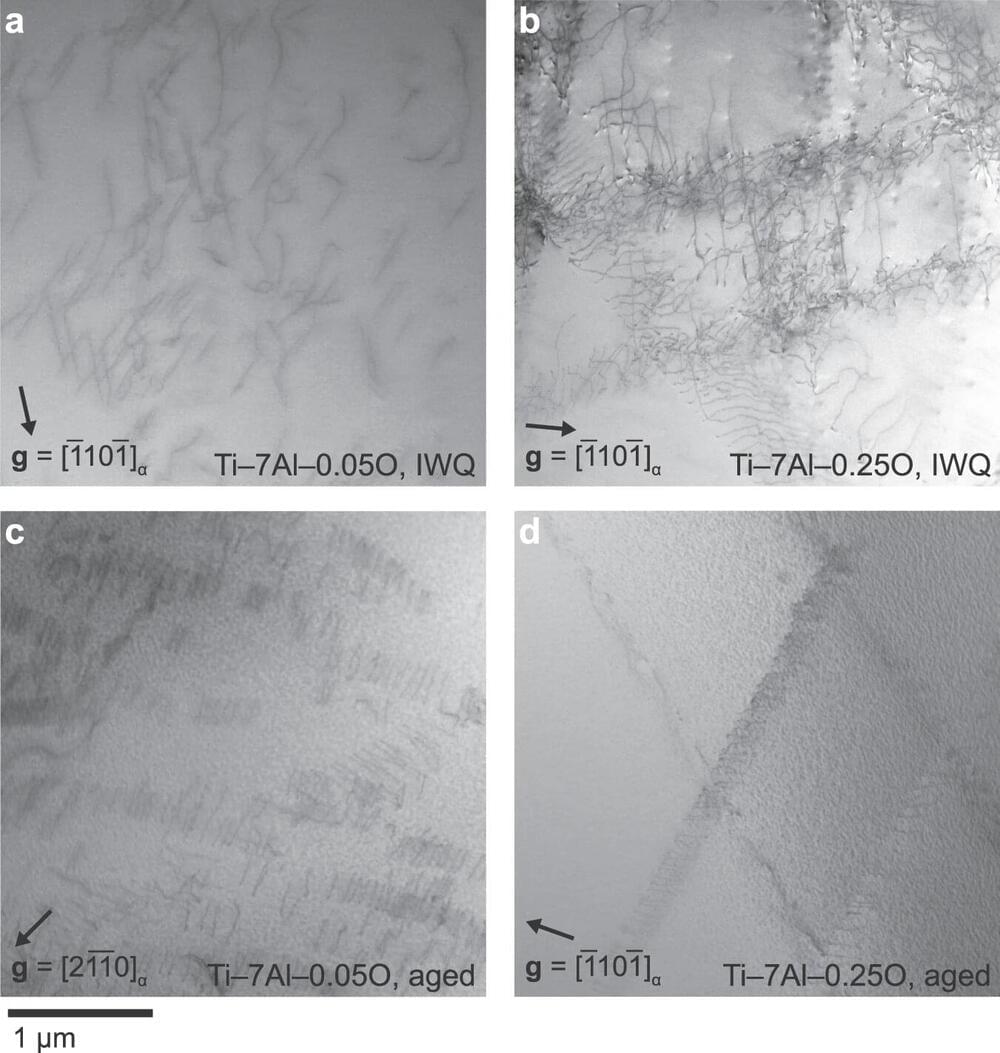

Physicist probes causes of life-shortening ‘dwell fatigue’ in titanium

“Dwell fatigue” is a phenomenon that can occur in titanium alloys when held under stress, such as a jet engine’s fan disc during takeoff. This peculiar failure mode can initiate microscopic cracks that drastically reduce a component’s lifetime.

The most widely used titanium alloy, Ti-6Al-4V, was not believed to exhibit dwell fatigue before the 2017 Air France Flight 66 incident, in which an Airbus en route from Paris to Los Angeles suffered fan disc failure over Greenland that forced an emergency landing. The analysis of that incident and several more recent concerns prompted the Federal Aviation Administration and European Union Aviation Safety Agency to coordinate work across the aerospace industry to determine the root causes of dwell fatigue.

According to experts, metals deform predominantly via dislocation slip—the movement of line defects in the underlying crystal lattice. Researchers hold that dwell fatigue can initiate when slip is restricted to narrow bands instead of occurring more homogenously in three dimensions. The presence of nanometer-scale intermetallic Ti3Al precipitates promotes band formation, particularly when processing conditions allow for their long-range ordering.

Zuckerberg Wants Facebook to Build a Mind-Reading Machine

Zuckerberg likes to quote Steve Jobs’ description of computers as “bicycles for the mind.” I can imagine him thinking, “What’s wrong with helping us pedal a little faster?”

And while I reflexively gag at Zuckerberg’s thinking, that isn’t meant to discount its potential to do great things or to think that holding it off will be easy or necessarily desirable. But at a minimum, we should demand a pause to ask hard questions about such barrier-breaking technologies—each quietly in our own heads, I should hasten to add, and then later as a society.

We need to pump the brakes on Silicon Valley, at least temporarily. For, if the Zuckerberg reflection tour has revealed anything, it is that even as he wrestles with the harms Facebook has wrought, he is busy dreaming up new ones.

Elon Musk sold $4 billion worth of Tesla stock following the Twitter

Why does the world’s richest person need more cash?

Days after agreeing to acquire Twitter for his initial offer of $44 billion, Elon Musk sold off Tesla stock worth nearly $4 billion in the days between November 4 and November 8, the Wall Street Journal.

Last year, Musk became the world’s richest person riding on the stock value of his electric car-making company, Tesla. At its peak price of $410 a piece, Musk’s personal worth reached a never-before figure of $340 billion last year. As we turned into the new year, Tesla stock started shedding the rapid gains, and as 2022 draws to a close, it is now down 45 percent, a Bloomberg report said.

Atomic changes in metals could lead to longer-lasting batteries

Researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) are studying the atomic-level changes in metals undergoing shear deformation in order to deduce the effects of physical forces on these materials, according to a report by Phys.org published on Monday.

The work could lead to many new and improved applications such as longer-lasting batteries and lighter vehicles.