If you need any proof that it doesn’t take the most advanced chip manufacturing processes to create an exascale-class supercomputer, you need look no further than the Sunway “OceanLight” system housed at the National Supercomputing Center in Wuxi, China.

Some of the architectural details of the OceanLight supercomputer came to our attention as part of a paper published by Alibaba Group, Tsinghua University, DAMO Academy, Zhejiang Lab, and Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence, which is running a pretrained machine learning model called BaGuaLu, across more than 37 million cores and 14.5 trillion parameters (presumably with FP32 single precision), and has the capability to scale to 174 trillion parameters (and approaching what is called “brain-scale” where the number of parameters starts approaching the number of synapses in the human brain). But, as it turns out, some of these architectural details were hinted at in the three of the six nominations for the Gordon Bell Prize last fall, which we covered here. To our chagrin and embarrassment, we did not dive into the details of the architecture at the time (we had not seen that they had been revealed), and the BaGuaLu paper gives us a chance to circle back.

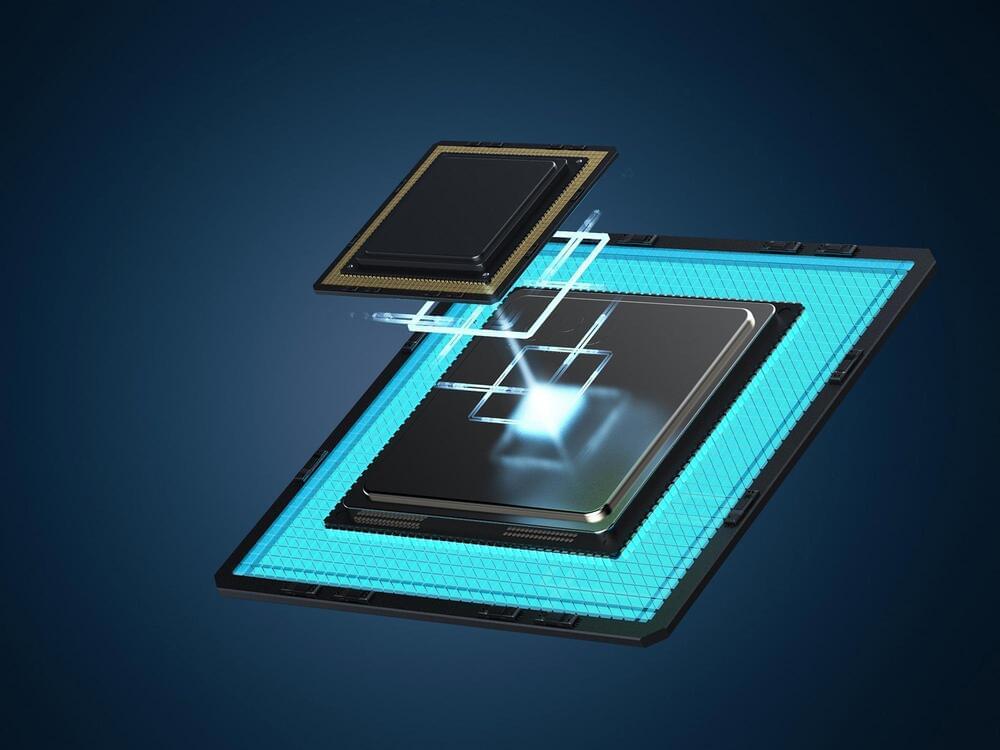

Before this slew of papers were announced with details on the new Sunway many-core processor, we did take a stab at figuring out how the National Research Center of Parallel Computer Engineering and Technology (known as NRCPC) might build an exascale system, scaling up from the SW26010 processor used in the Sunway “TaihuLight” machine that took the world by storm back in June 2016. The 260-core SW26010 processor was etched by Chinese foundry Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation using 28 nanometer processes – not exactly cutting edge. And the SW26010-Pro processor, etched using 14 nanometer processes, is not on an advanced node, but China is perfectly happy to burn a lot of coal to power and cool the OceanLight kicker system based on it. (Also known as the Sunway exascale system or the New Generation Sunway supercomputer.)