One of the fundamental challenges of physics is the reconciliation of Einstein’s theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. The necessity to critically question these two pillars of modern physics arises, for example, from extremely high-energy events in the cosmos, which so far can only ever be explained by one theory at a time, but not both theories in harmony. Researchers around the world are therefore searching for deviations from the laws of quantum mechanics and relativity that could open up insights into a new field of physics.

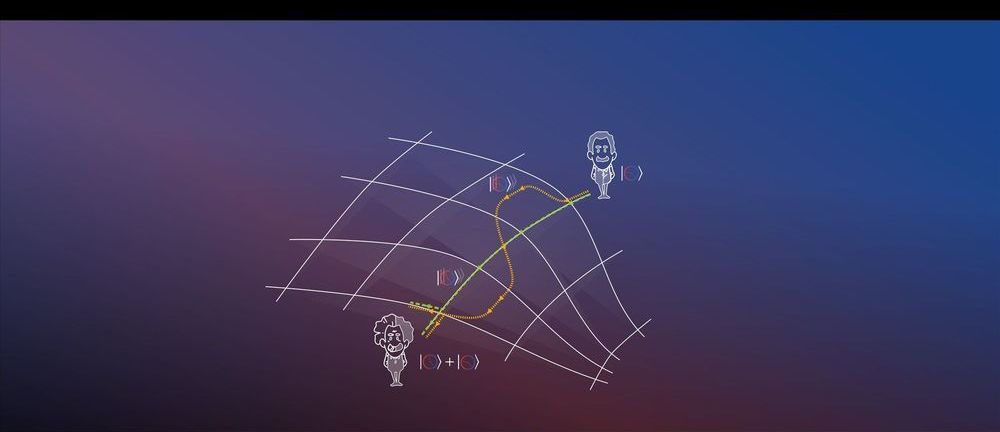

For a recent publication, scientists from Leibniz University Hannover and Ulm University have taken on the twin paradox known from Einstein’s special theory of relativity. This thought experiment revolves around a pair of twins: While one brother travels into space, the other remains on Earth. Consequently, for a certain period of time, the twins are moving in different orbits in space. The result when the pair meets again is quite astounding: The twin who has been travelling through space has aged much less than his brother who stayed at home. This phenomenon is explained by Einstein’s description of time dilation: Depending on the speed and where in the gravitational field two clocks move relative to each other, they tick at different speeds.

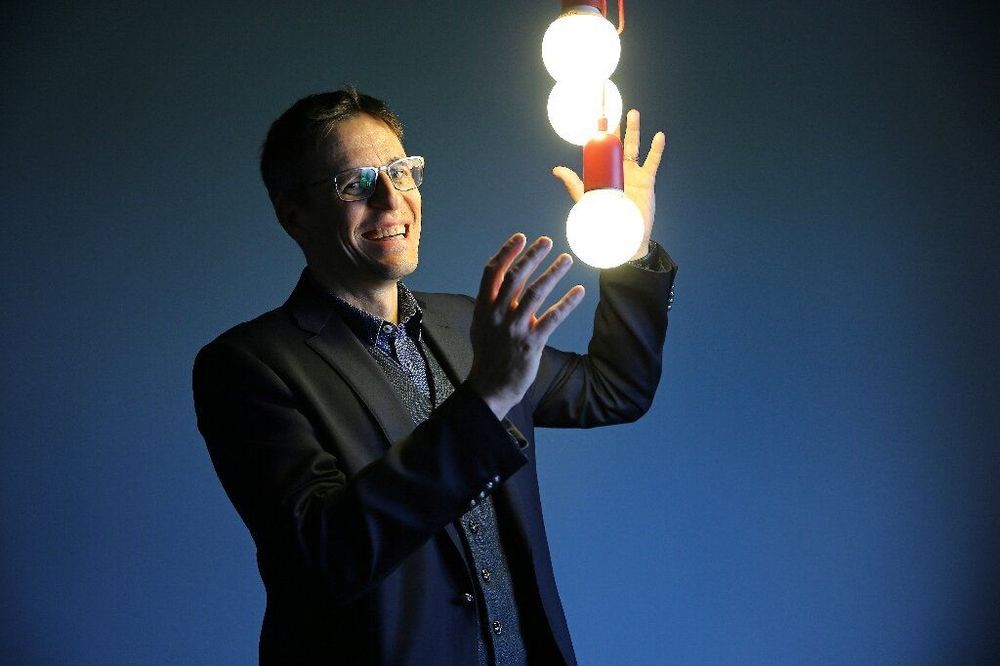

For the publication in Science Advances, the authors assumed a quantum-mechanical variant of the twin paradox with only one twin. Thanks to the superposition principle of quantum mechanics, this twin can move along two paths at the same time. In the researchers’ thought experiment, the twin is represented by an atomic clock. “Such clocks use the quantum properties of atoms to measure time with high precision. The atomic clock itself is therefore a quantum-mechanical object and can move through space-time on two paths simultaneously due to the superposition principle. Together with colleagues from Hannover, we have investigated how this situation can be realised in an experiment,” explains Dr. Enno Giese, research assistant at the Institute of Quantum Physics in Ulm. To this end, the researchers have developed an experimental setup for this scenario on the basis of a quantum-physical model.