(Front row from left) Expedition 64 crew members Kate Rubins, Sergey Ryzhikov and Sergey Kud-Sverchkov join Expedition 63 crew members (back row from left) Ivan Vagner, Anatoly Ivanishin and Chris Cassidy inside the space station’s Zvezda service module. N…

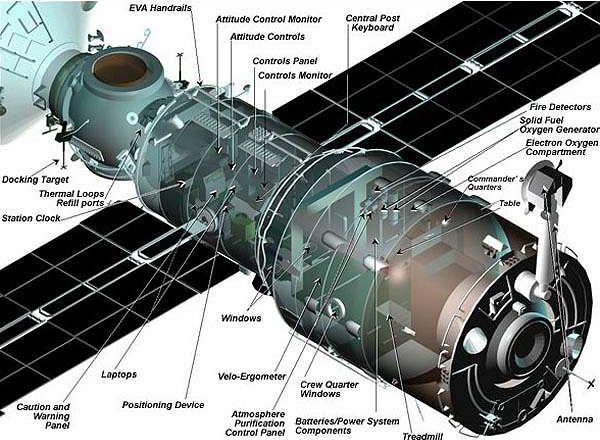

NASA astronaut Kate Rubins and cosmonauts Sergey Ryzhikov and Sergey Kud-Sverchkov of the Russian space agency Roscosmos joined Expedition 63 Commander Chris Cassidy of NASA and cosmonauts Anatoly Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner aboard the International Space Station when the hatches between the Soyuz spacecraft and the orbiting laboratory officially opened at 7:07 a.m. EDT.

The arrival temporarily restores the station’s crew complement to six for the remainder of Expedition 63.

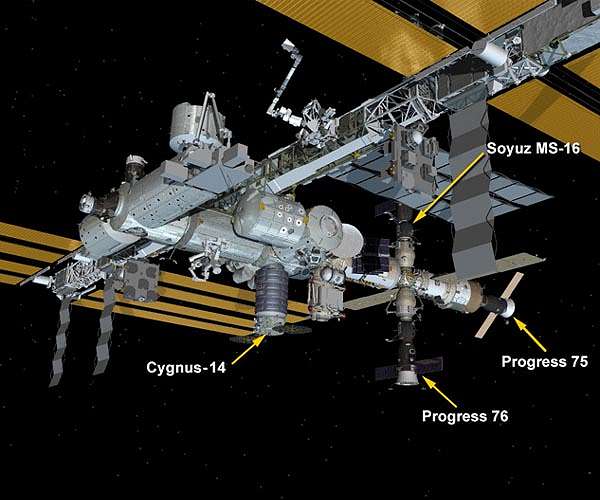

Expedition 64 begins Wednesday, Oct. 21, with the departure of Cassidy, Vagner, and Ivanishin in the Soyuz MS-16 spacecraft that brought them to the station on April 9. Cassidy will hand command of the station to Ryzhikov during a ceremony with all crew members that is scheduled for 4:15 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 20 and will air live on NASA Television and the agency’s website.