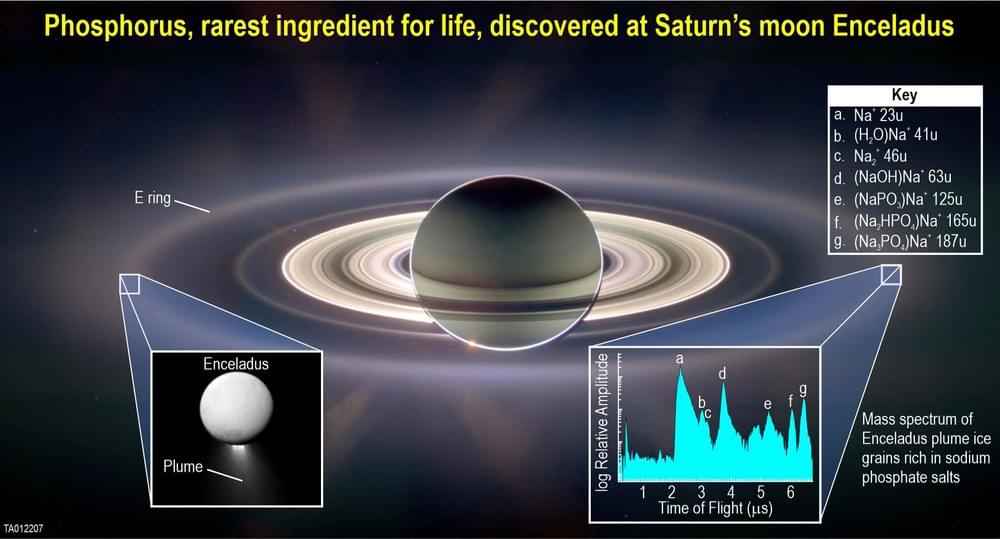

Key building block for life found at Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Fibonacci numbers are seen in the natural structures of various plants, such as the florets in sunflower heads, areoles on cacti stems, and scales in pine cones. [HackerBox] has developed a Fibonacci Spiral LED Badge to bring this natural phenomenon to your electronics.

To position each of the 64 addressable LEDs within the PCB layout, [HackerBox] computed the polar (r,θ) coordinates in a spreadsheet according to the Vogel model and then converted them to rectangular (x, y) coordinates. A little more math translates the points “off origin” into the center of the PCB space and scale them out to keep the first two 5 mm LEDs from overlapping. Finally, the LED coordinates were pasted into the KiCad PCB design file.

An RP2040 microcontroller controls the show, and a switch on the badge selects power between USB and three AA batteries and a DC/DC boost converter. The PCB also features two capacitive touch pads. [HackerBox] has published the KiCad files for the badge, and the CircuitPython firmware is shared with the project. If C/C++ is more your preference, the RP2040 MCU can also be programmed using the Arduino IDE.

Varda Space Industries aims to kickstart a new era of mass production of pharmaceuticals and other materials from Earth’s orbit.

A California-based startup co-founded by a SpaceX veteran, Varda Space Industries, announced it has successfully deployed its first satellite, W-Series 1, in orbit.

The company aims to kickstart the mass production of materials in space that either can’t be produced on Earth or are developed faster and with higher quality in microgravity conditions.

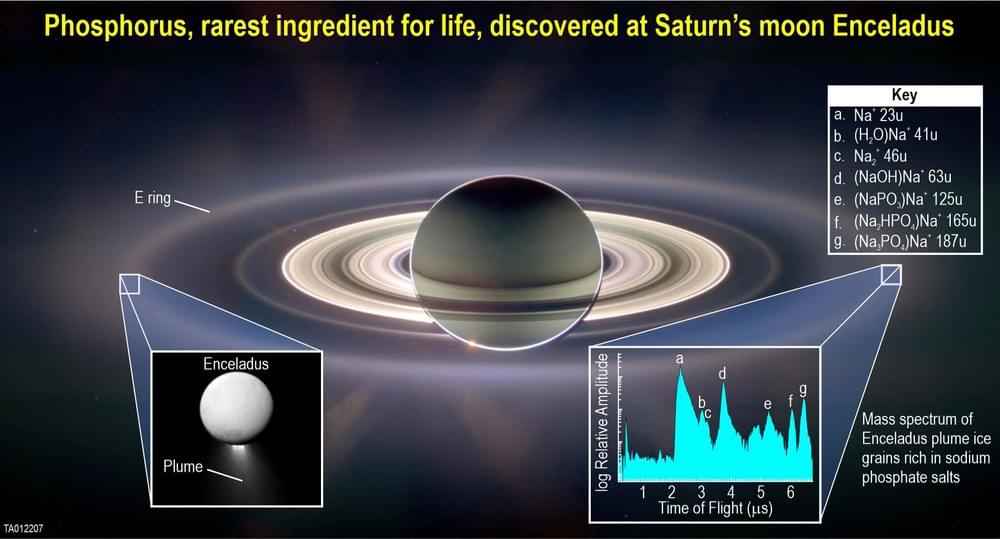

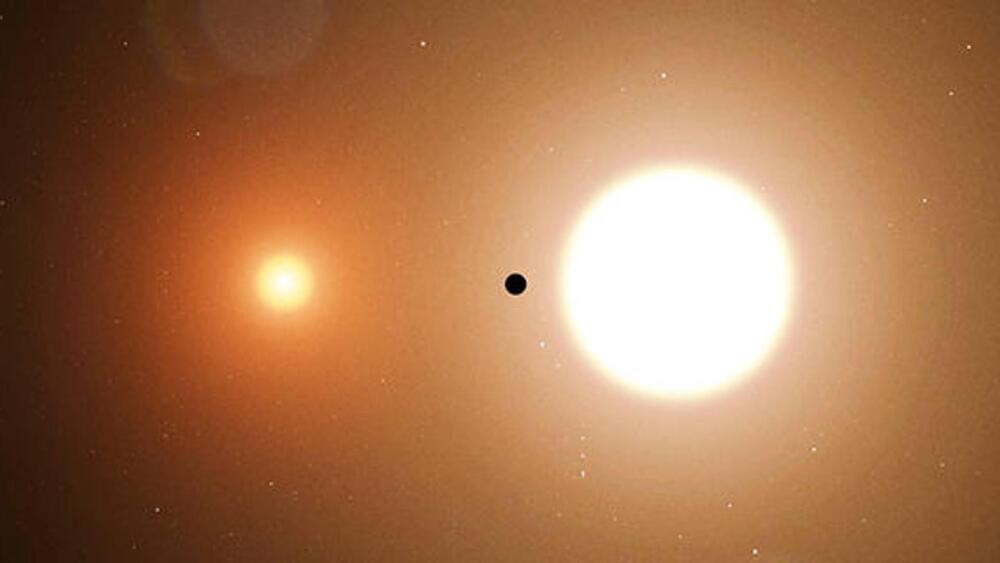

BEBOP-1c is the newly discovered planet, while the first one in this system is TOI-1338b.

The term ‘Tatooine’ is pretty popular in science fiction series such as Star Wars.

Now, in a huge breakthrough, scientists have discovered a new exoplanet in an already known Tatooine system or circumbinary system.

Researchers have reached a significant milestone in the field of quantum gravity research, finding preliminary statistical support for quantum gravity.

In a study published in Nature Astronomy on June 12, a team of researchers from the University of Naples “Federico II,” the University of Wroclaw, and the University of Bergen examined a quantum-gravity model of particle propagation in which the speed of ultrarelativistic particles decreases with rising energy. This effect is expected to be extremely small, proportional to the ratio between particle energy and the Planck scale, but when observing very distant astrophysical sources, it can accumulate to observable levels. The investigation used gamma-ray bursts observed by the Fermi telescope and ultra-high-energy neutrinos detected by the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, testing the hypothesis that some neutrinos and some gamma-ray bursts might have a common origin but are observed at different times as a result of the energy-dependent reduction in speed.

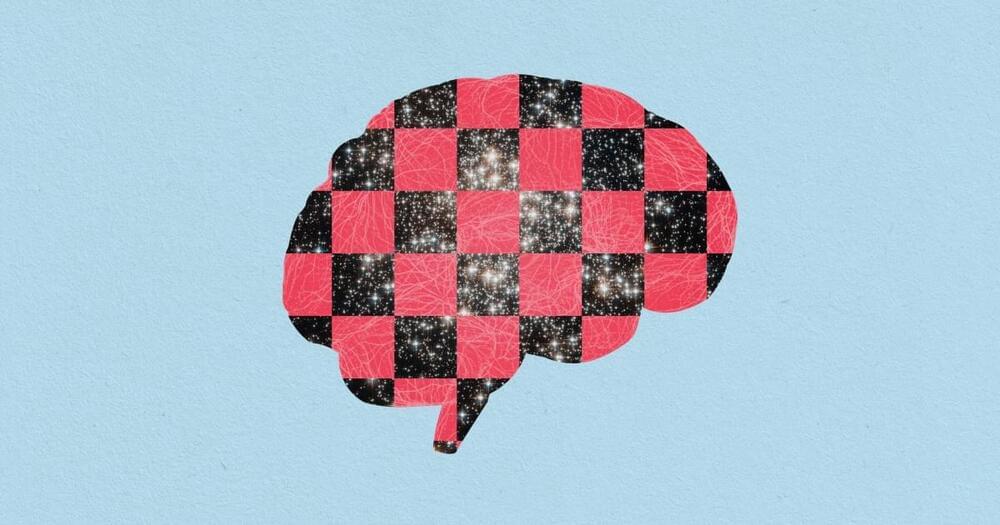

For example, scientists have recently emphasized that the physical organization of the Universe mirrors the structure of a brain. Theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder — renowned for her skepticism — wrote a bold article for Time Magazine in August of 2022 titled “Maybe the Universe Thinks. Hear Me Out,” which describes the similarities. Like our nervous system, the Universe has a highly interconnected, hierarchical organization. The estimated 200 billion detectable galaxies aren’t distributed randomly, but lumped together by gravity into clusters that form even larger clusters, which are connected to one another by “galactic filaments,” or long thin threads of galaxies. When one zooms out to envision the cosmos as a whole, the “cosmic web” formed by these clusters and filaments looks strikingly similar to the “connectome,” a term that refers to the complete wiring diagram of the brain, which is formed by neurons and their synaptic connections. Neurons in the brain also form clusters, which are grouped into larger clusters, and are connected by filaments called axons, which transmit electrical signals across the cognitive system.

Hossenfelder explains that this resemblance between the cosmic web and the connectome is not superficial, citing a rigorous study by a physicist and a neuroscientist that analyzed the features common to both, and based on the shared mathematical properties, concluded that the two structures are “remarkably similar.” Due to these uncanny similarities, Hossenfelder speculates as to whether the Universe itself could be thinking.

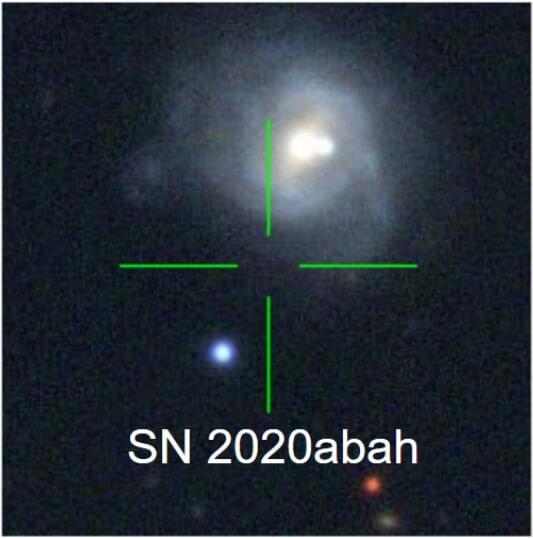

An international team of astronomers reports the detection of 12 new long-rising Type II supernovae as part of the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) Census of the Local Universe (CLU). The discovery, published June 1 on the arXiv pre-print repository, nearly doubles the number of known supernovae of this subclass.

Type II supernovae (SNe) are the results of rapid collapse and violent explosion of massive stars (with masses above 8.0 solar masses). They are distinguished from other SNe by the presence of hydrogen in their spectra. Based on the shape of their light curves, they are usually divided into Type IIL and Type IIP. Type IIL SNe show a steady (linear) decline after the explosion, while Type IIP exhibit a period of slower decline (a plateau) that is followed by a normal decay.

Some Type II SNe are characterized by their unusual long rises to peak—lasting more than 40 days. Observations suggest that, in general, such long-rising SNe originate from more compact (with radii below 100 solar radii), massive (with masses of about 20 solar masses) stars, and have higher explosion energies. However, although three decades have passed since the discovery of the first long-rising Type II SNe, designated SN 1987A, only 16 explosions of this subclass have been identified in the local universe.