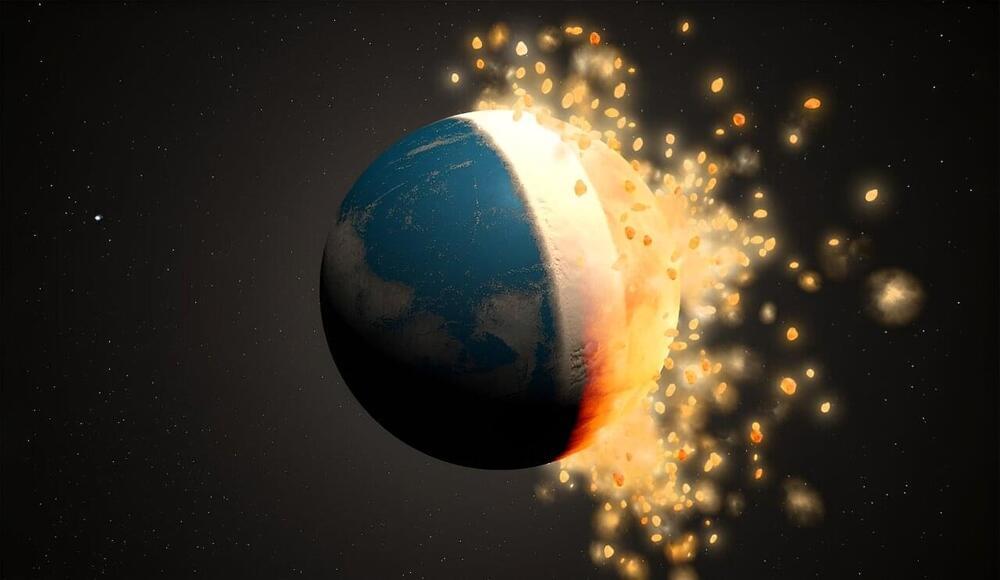

Astronomers detected the dusty afterglow of a massive planetary collision in a star system 3,600 light-years away, where two giant icy worlds met their end.

A new study reports conclusive evidence for the breakdown of standard gravity in the low acceleration limit from a verifiable analysis of the orbital motions of long-period, widely separated, binary stars, usually referred to as wide binaries in astronomy and astrophysics.

The study carried out by Kyu-Hyun Chae, professor of physics and astronomy at Sejong University in Seoul, used up to 26,500 wide binaries within 650 light years (LY) observed by European Space Agency’s Gaia space telescope. The study was published in the 1 August 2023 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

For a key improvement over other studies Chae’s study focused on calculating gravitational accelerations experienced by binary stars as a function of their separation or, equivalently the orbital period, by a Monte Carlo deprojection of observed sky-projected motions to the three-dimensional space.

The richest man in the world is building a super-intelligent AI to understand the true nature of the universe. This is what the project means for investors.

Elon Musk held a Twitter Spaces event in early July to reveal X.ai, his newest AI business. X.ai researchers will focus on science, while also building applications for enterprises and consumers.

To participate, investors should continue to buy Arista Networks ANET (ANET).

Watch live as NASA astronaut Frank Rubio, the new record holder for the longest single U.S. spaceflight, returns home from the International Space Station. T…

Rocks and soil collected from the asteroid Bennu and brought back to Earth last month by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx probe are rich in carbon and contain water-bearing clay minerals that date back to the birth of the solar system, scientists said Wednesday. The discovery gives critical insight into the formation of our planet and supports theories about how water may have arrived on Earth in the distant past.

The clay minerals “have water locked inside their crystal structure,” said Dante Lauretta, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona and the principal investigator of the asteroid sample return mission, while revealing initial photographs of the material.

The powdery material that NASA officials unveiled on Wednesday looked like asphalt or charcoal, but was easily worth more than its weight in diamonds. The fragments were from a world all their own—pieces of the asteroid Bennu, collected and returned to Earth for analysis by the OSIRIS-REx mission. The samples hold chemical clues to the formation of our solar system and the origin of life-supporting water on our planet.

The clay and minerals from the 4.5 billion-year-old rock had been preserved in space’s deep freeze since the dawn of the solar system. Last month, after a seven-year-long space mission, they parachuted to a desert in Utah, where they were whisked away by helicopter.

And now those pristine materials sit in an airtight vessel in a clean room at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, where researchers like University of Arizona planetary scientist Dante Lauretta are getting their first chance to study the sample up close.

Some asteroids are dense. So dense in fact, that they may contain heavy elements outside of the periodic table, according to a new study on mass density.

The team of physicists from The University of Arizona say they were motivated by the possibility of Compact Ultradense Objects (CUDOs) with a mass density greater than Osmium, the densest naturally occurring, stable element, with its 76 protons.

“In particular, some observed asteroids surpass this mass density threshold. Especially noteworthy is the asteroid 33 Polyhymnia,” the team writes in their study, adding that “since the mass density of asteroid 33 Polyhymnia is far greater than the maximum mass density of familiar atomic matter, it can be classified as a CUDO with an unknown composition.”

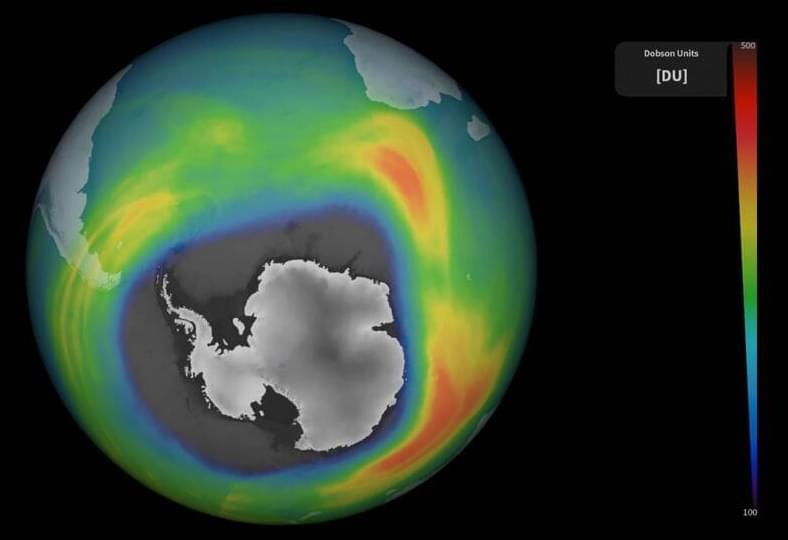

One of the largest ozone holes on record has been observed over Antarctica this year, according to measurements from the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite.

A lower concentration of O3 molecules

The ozone hole is a section of the stratosphere of Earth where there is a markedly lower concentration of ozone (O3) molecules. The ozone layer is severely diminishing in some parts of the stratosphere, although it is not technically a hole. By absorbing the bulk of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the ozone layer, a region of the Earth’s atmosphere with a relatively high concentration of ozone molecules, plays a crucial role in safeguarding life on the planet.

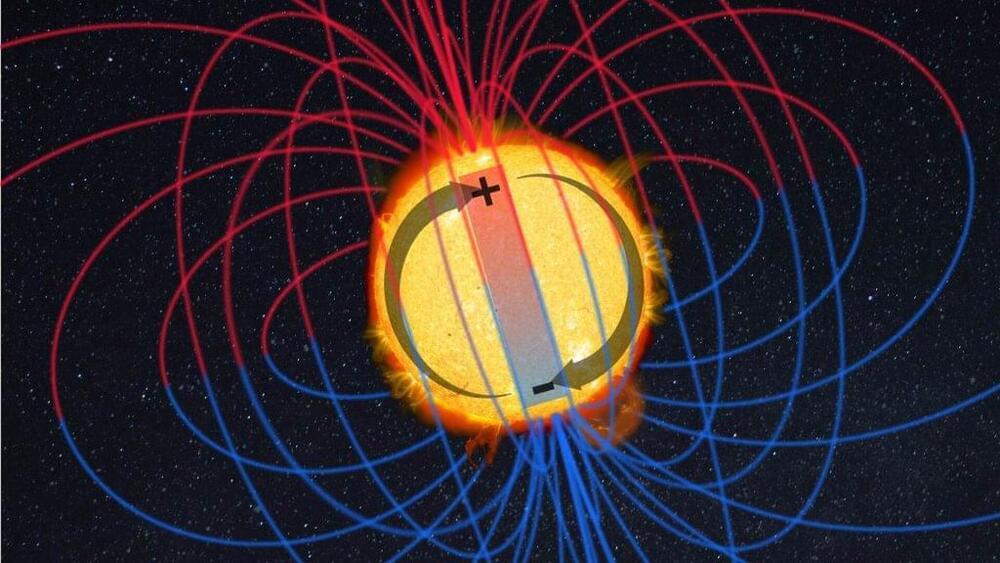

Oct. 5, 2023: (Spaceweather.com) The sun is about to lose something important: Its magnetic poles.

Recent measurements by NASA’s Solar Dynamic Observatory reveal a rapid weakening of magnetic fields in the polar regions of the sun. North and south magnetic poles are on the verge of disappearing. This will lead to a complete reversal of the sun’s global magnetic field perhaps before the end of the year.

An artist’s concept of the sun’s dipolar magnetic field. Credit: NSF/AURA/NSO.

Scientists at Yale and the Southwest Research Institute (SRI) say they’ve hit the jackpot with some valuable new information about the story of gold.

It’s a story that begins with violent collisions of large objects in space, continues in a half-melted region of Earth’s mantle, and ends with precious metals finding an unlikely resting spot much closer to the planet’s surface than scientists would have predicted.

Jun Korenaga, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Simone Marchi, a researcher at SRI in Boulder, Colorado, provide details in a study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.