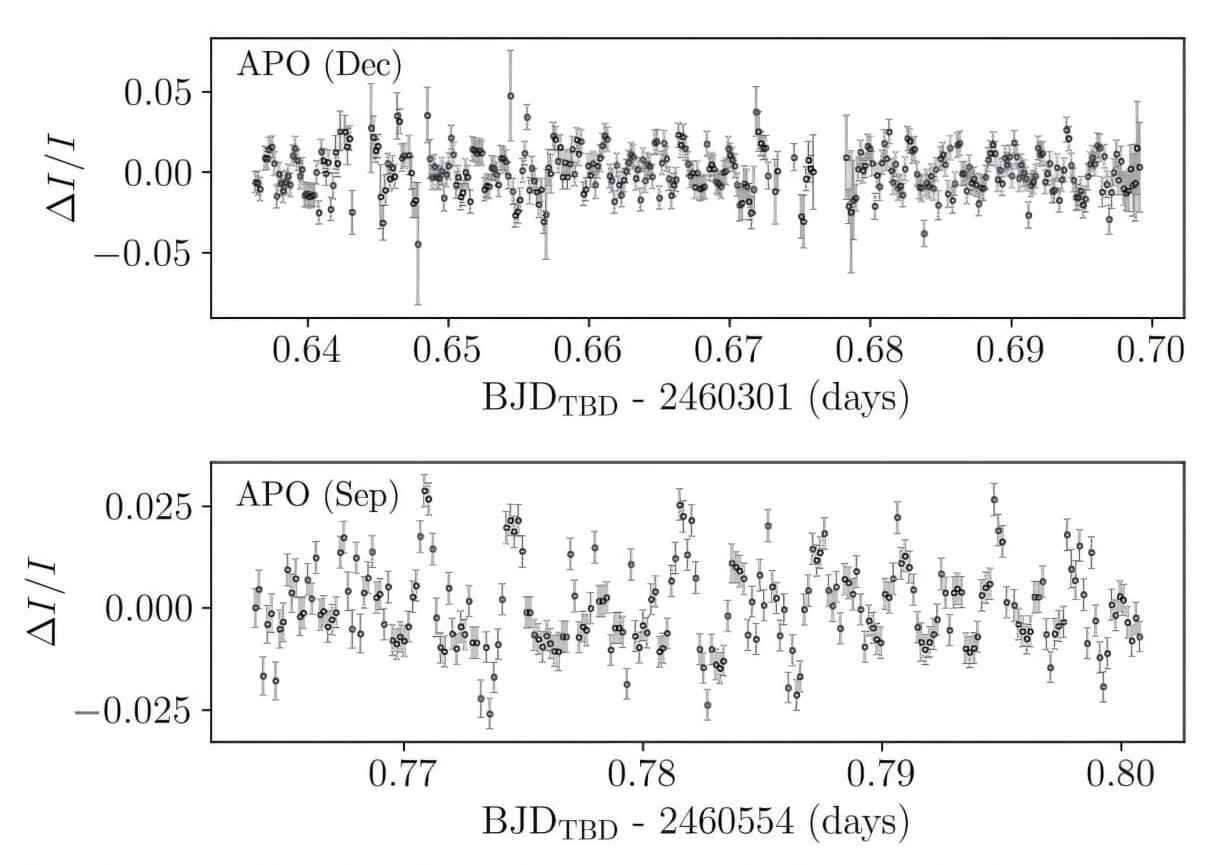

Using the Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) and the Apache Point Observatory (APO), an international team of astronomers has detected 19 pulsation modes in an ultra-massive white dwarf known as WD J0135+5722. The discovery, presented on the arXiv preprint server, makes WD J0135+5722 the richest pulsating ultra-massive white dwarf known to date.

White dwarfs (WDs) are stellar cores left behind after a star has exhausted its nuclear fuel. Due to their high gravity, they are known to have atmospheres of either pure hydrogen or pure helium. However, a small fraction of WDs shows traces of heavier elements.

In pulsating WDs, luminosity varies due to non-radial gravity wave pulsations within these objects. One subtype of pulsating WDs is known as DAVs, or ZZ Ceti stars—these are WDs of spectral type DA, having only hydrogen absorption lines in their spectra.