MIT engineers have developed ultralight fabric solar cells that can quickly and easily turn any surface into a power source.

These durable, flexible solar cells, which are much thinner than a human hair, are glued to a strong, lightweight fabric, making them easy to install on a fixed surface. They can provide energy on the go as a wearable power fabric or be transported and rapidly deployed in remote locations for assistance in emergencies. They are one-hundredth the weight of conventional solar panels, generate 18 times more power-per-kilogram, and are made from semiconducting inks using printing processes that can be scaled in the future to large-area manufacturing.

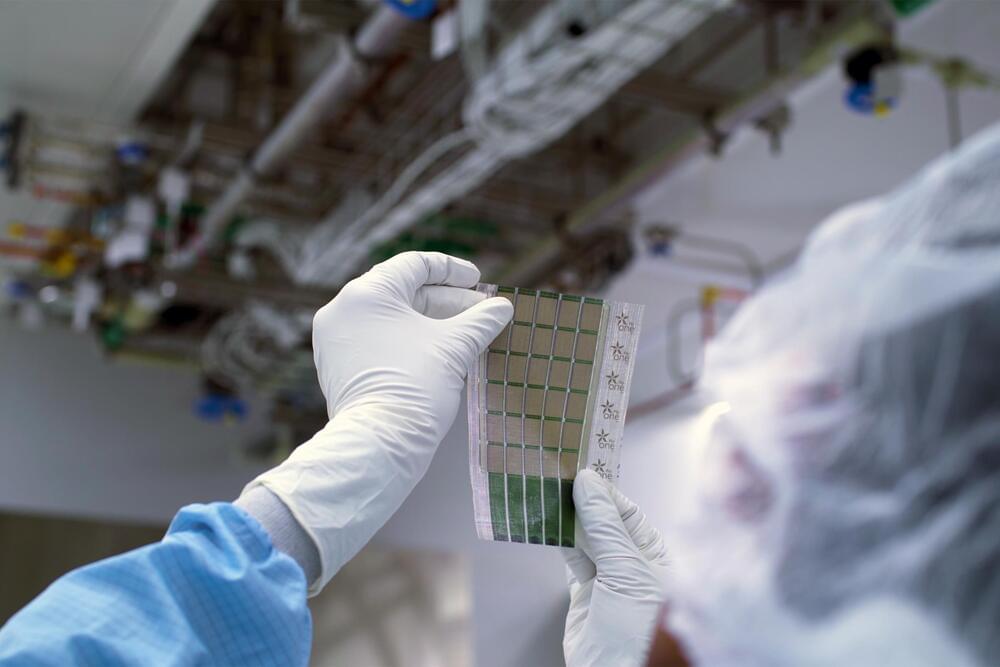

The thin-film solar cells weigh about 100 times less than conventional solar cells while generating about 18 times more power-per-kilogram. (Image: Melanie Gonick, MIT)