Interest in rejuvenation biotechnology is growing in the investment quarter.

Mainstream interest in rejuvenation biotechnology is growing.

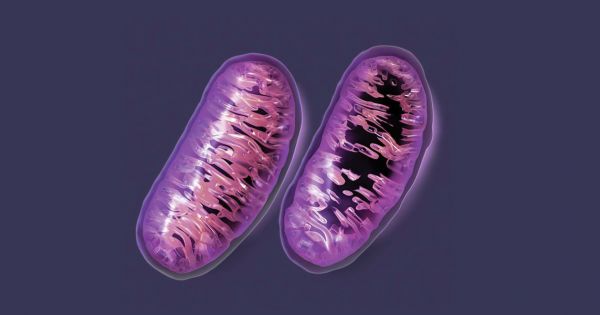

“Investment in the development of rejuvenation therapies represents an enormous opportunity for profit; these are products for which every adult human being much over the age of 30 is a potential customer at some price point. That is larger than near every existing industry, either within or outside the field of medicine, even given that customers will only purchase such a therapy once every few years, for clearance of metabolic waste, or even just once, for treatments like the SENS approach of allotopic expression of mitochondrial genes. Among the first successful companies in this space, some will grow to become among the largest in the world: I’d wager that the Ford or Microsoft of rejuvenation will be a lot larger than the actual Ford of automobiles or Microsoft of personal computing.”