Uganda is preparing to launch its first satellite by August 2022. The satellite, PearlAfricaSat-1, is the latest mission from the Joint Global Multi-Nation Birds Satellite project. The initiative began in October 2019 as part of a directive by Uganda’s President to develop a National Space Agency and Institute.

Uganda signed the collaborative research agreement with the Kyushu Institute of Technology (Kyutech), Japan. The agreement involved enrolling and upskilling three graduate engineers to design, build, test, and launch the first satellite for Uganda. Consequently, Japan registered three Ugandan graduate engineers, including; Bonny Omara, Edgar Mujunu, and Derrick Tebuseke.

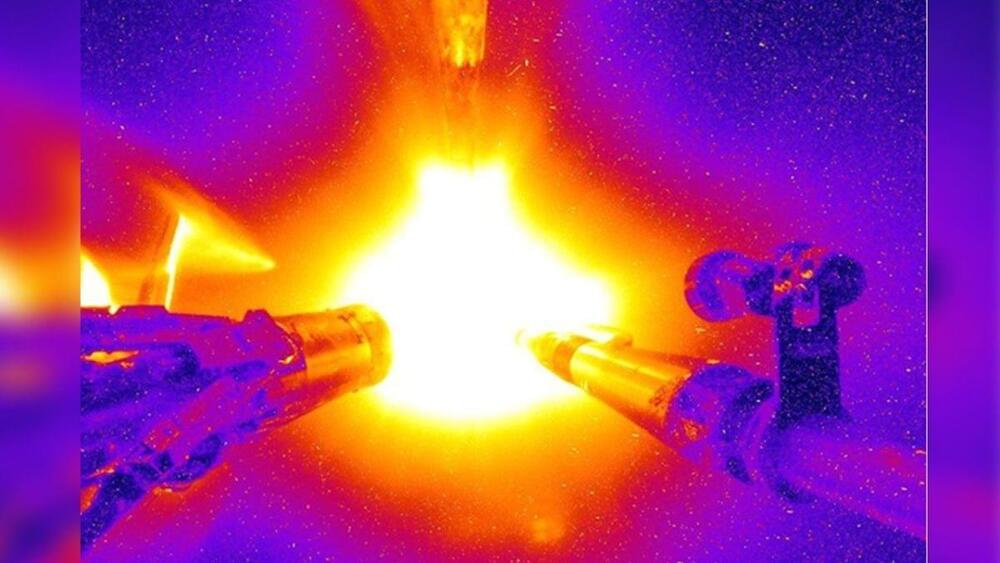

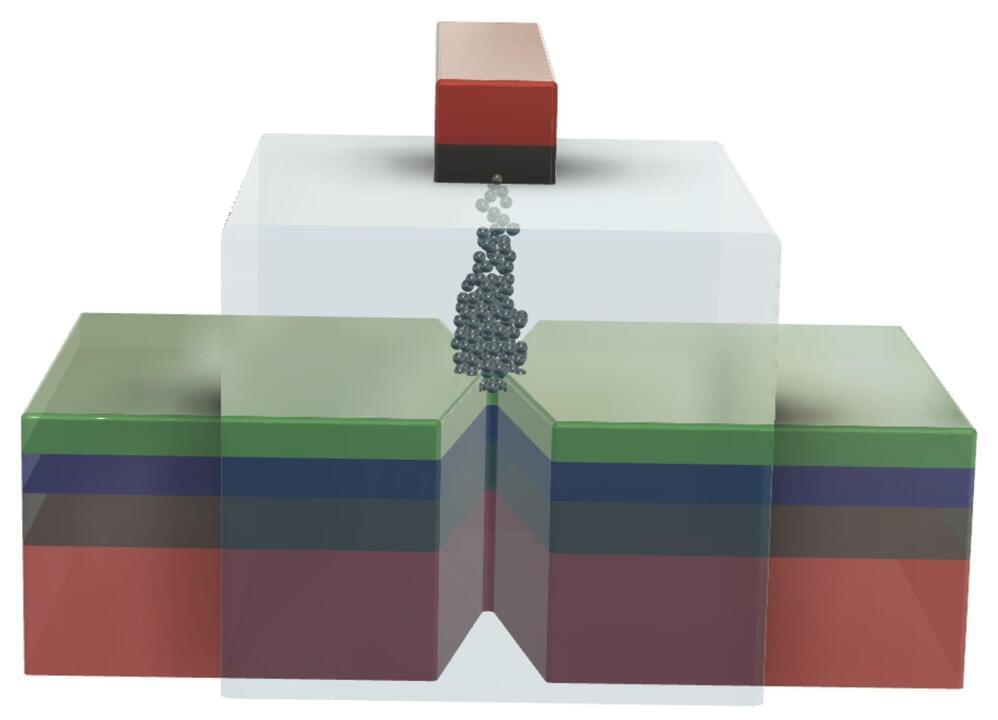

The core missions for PearlAfricaSat-1 are a multispectral camera payload. The Multispectral Camera mission will provide about 20-metre resolution images for Uganda to facilitate water quality, soil fertility, and land use and cover analysis. The satellite will play a vital role in the oil and gas operation by monitoring the East African crude oil pipeline. This will enable accurate weather forecasts by gathering remote sensor data for predicting landslides and drought. Once the satellite reaches orbit, an Uganda ground station will monitor its health status for a few days before it starts executing its mission.