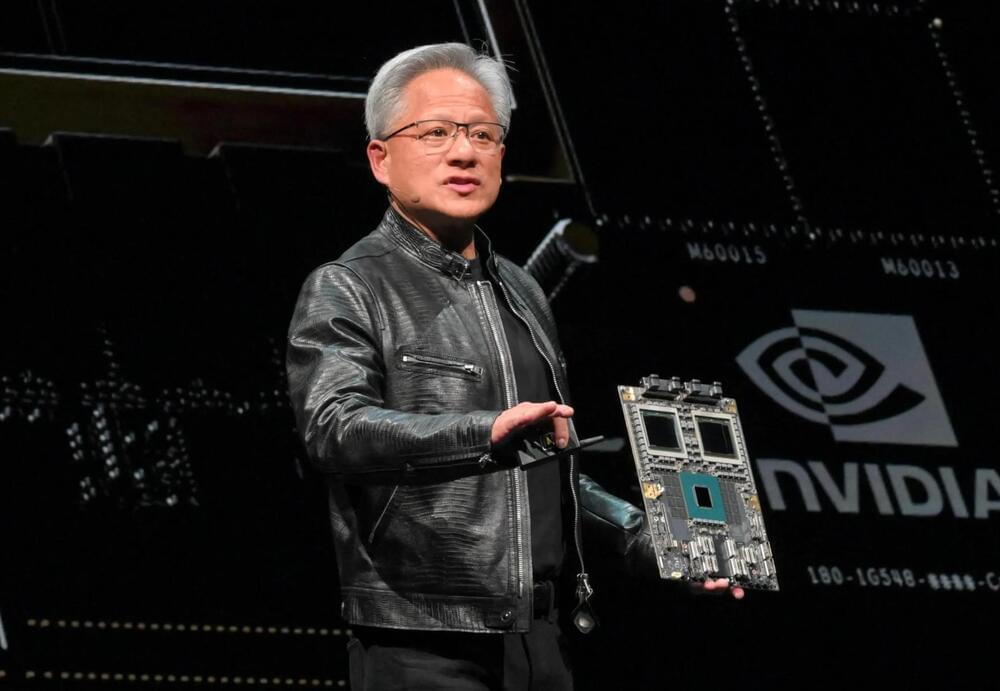

Microsoft leads the AI GPU race, purchasing nearly 500k NVIDIA Hopper GPUs in 2024, while other tech giants also invest heavily in AI.

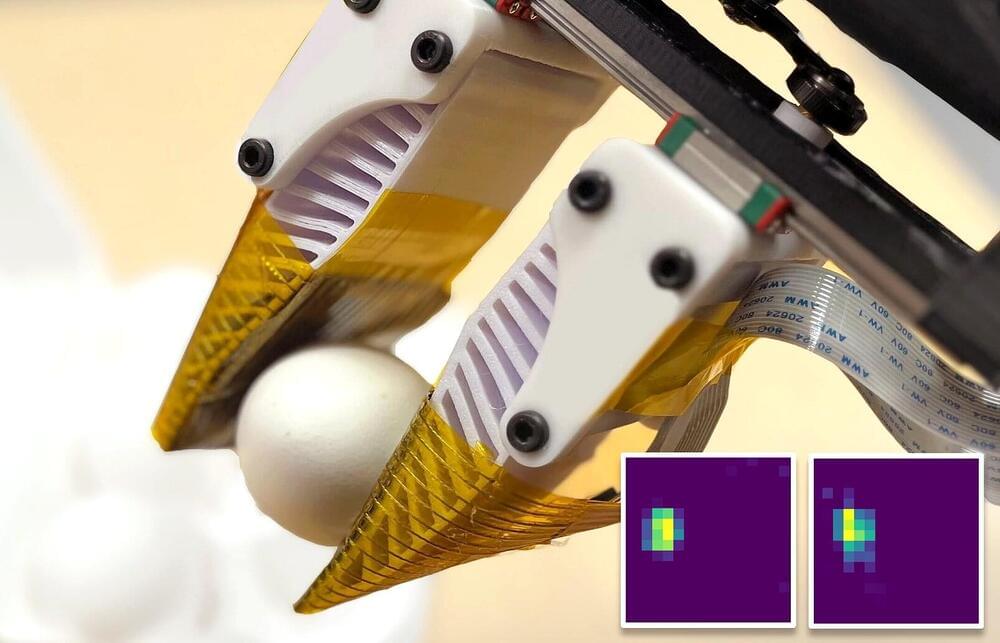

To assist humans with household chores and other everyday manual tasks, robots should be able to effectively manipulate objects that vary in composition, shape and size. The manipulation skills of robots have improved significantly over the past few years, in part due to the development of increasingly sophisticated cameras and tactile sensors.

Researchers at Columbia University have developed a new system that simultaneously captures both visual and tactile information. The tactile sensor they developed, introduced in a paper presented at the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL) 2024 in Munich, could be integrated onto robotic grippers and hands, to further enhance the manipulation skills of robots with varying body structures.

The paper was published on the arXiv preprint server.

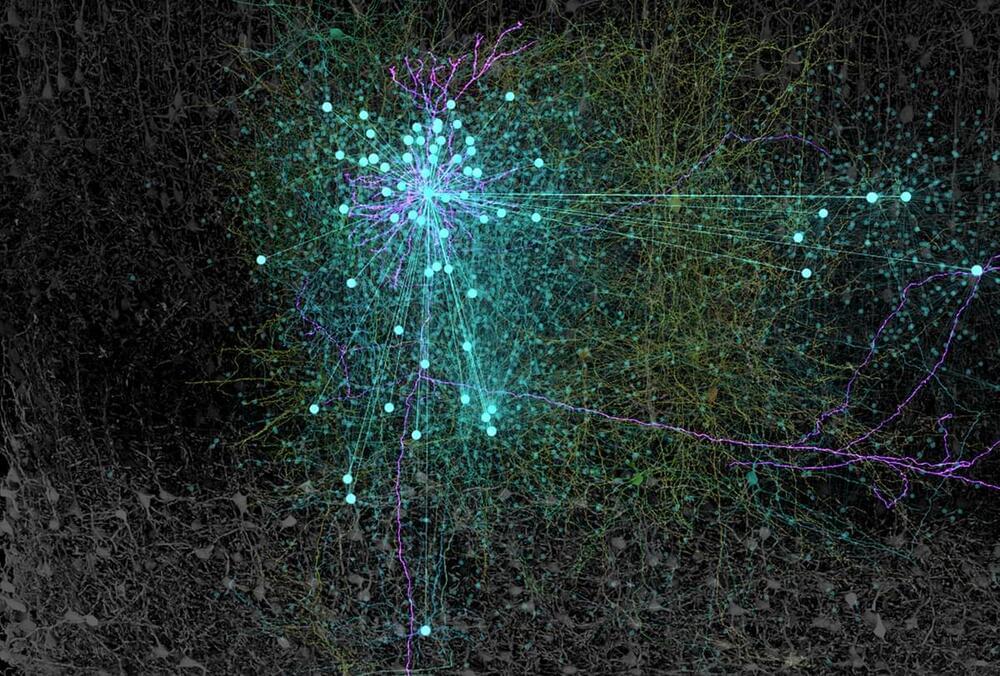

In a new study published in PNAS Nexus, scientists have demonstrated that artificial intelligence can predict different types of human intelligence by analyzing connections in the brain. Using neuroimaging data from hundreds of healthy adults, they found that predictions were most accurate for general intelligence, followed by crystallized intelligence, and then fluid intelligence. The findings shed light on the distributed and dynamic nature of intelligence, demonstrating that it arises from the global interplay of brain networks rather than isolated regions.

While prior research has established that intelligence is not localized to a single brain region but rather involves distributed networks, many studies have relied on traditional methods that focus on isolated brain features. These approaches have offered limited insights into how intelligence arises from the interplay of brain structure and function. By employing machine learning to analyze brain connectivity, the researchers aimed to overcome these limitations.

A key focus of the study was the distinction between three major forms of intelligence: general, fluid, and crystallized. General intelligence, often referred to as “g,” is a broad measure of cognitive ability that encompasses reasoning, problem-solving, and learning across a variety of contexts. It serves as an overarching factor, capturing shared elements between specific cognitive skills.

Today I have the pleasure of speaking with a visionary thinker and innovator who’s making waves in the world of artificial intelligence and the future of human health. Dr. Ben Goertzel is the founder and CEO of SingularityNET, a decentralized AI platform that aims to democratize access to advanced artificial intelligence. He’s also the mind behind OpenCog, an open-source project dedicated to developing artificial general intelligence, and he’s a key figure at Hanson Robotics, where he helped create the well-known AI robot, Sophia.

Beyond AI, Dr. Goertzel is deeply involved in exploring how technology can enhance human longevity, contributing to initiatives like Rejuve, which aims to leverage AI and blockchain to advance life extension research. With a career that spans cognitive science, AI development, and innovative health tech, Dr. Goertzel is shaping the future in ways that will impact all of us. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Ben Goertzel!

PRODUCTION CREDITS

⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺⎺

Host, Writer — @emmettshort.

Executive Producer — Keith Comito

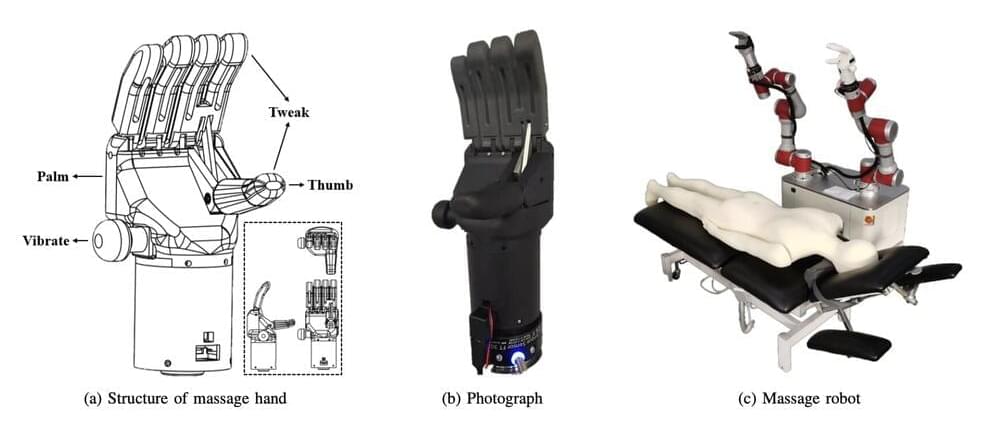

In recent years, roboticists have developed a wide range of systems that could eventually be introduced in health care and assisted living facilities. These include both medical robots and robots designed to provide companionship or assistance to human users.

Researchers at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology recently developed a robotic system that could give human users a massage that employs traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) techniques. This new robot, introduced in a paper on the arXiv preprint server, could eventually be deployed in health care, wellness and rehabilitation facilities as additional therapeutic tools for patients who are experiencing different types of pain or discomfort.

“We adopt an adaptive admittance control algorithm to optimize force and position control, ensuring safety and comfort,” wrote Yuan Xu, Kui Huang, Weichao Guo and Leyi Du in their paper. “The paper analyzes key TCM techniques from kinematic and dynamic perspectives and designs robotic systems to reproduce these massage techniques.”

Westlake University in China and the California Institute of Technology have designed a protein-based system inside living cells that can process multiple signals and make decisions based on them.

The researchers have also introduced a unique term, “perceptein,” as a combination of protein and perceptron. Perceptron is a foundational artificial neural network concept, effectively solving binary classification problems by mapping input features to an output decision.

By merging concepts from neural network theory with protein engineering, “perceptein” represents a biological system capable of performing classification computations at the protein level, similar to a basic artificial neural network. This “perceptein” circuit can classify different signals and respond accordingly, such as deciding to stay alive or undergo programmed cell death.