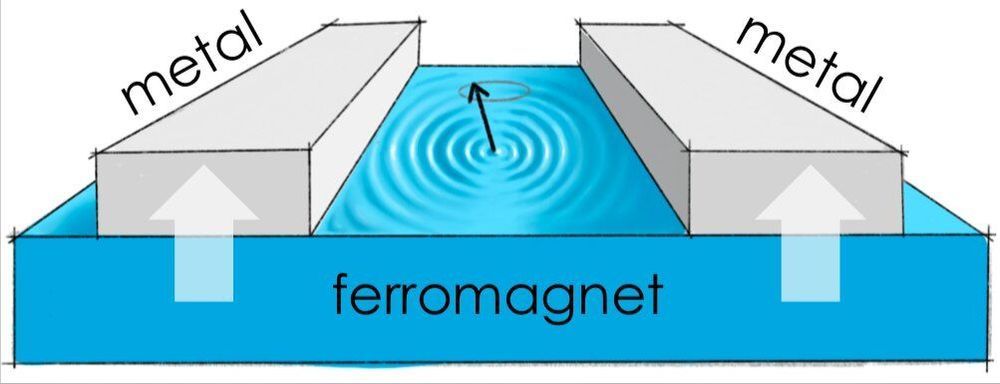

A team of researchers at Utrecht University, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and the University of Konstanz has recently proposed a new method to determine magnon coherence in solid-state devices. Their study, outlined in a paper published in Physical Review Letters, shows that cross-correlations of pure spin currents injected by a ferromagnet into two metal leads normalized by their dc value replicate the behavior of the second-order optical coherence function, referred to as g, when magnons are driven far from equilibrium.

“Consider a big room full of people having a party,” Akash Kamra, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “These people can either behave as in a night club, bumping into each other in an uncoordinated way and with chaotic movements, or the party people might be directed by a common host, such as at a wedding party. Such a ‘condensed’ crowd of people moves swiftly without bumping into each other.”

Kamra draws an analogy between the party situations he described and magnons, quantum particles that correspond to a specific decrease in magnetic strength, traveling as a unit through a magnetic substance. In his analogy, an uncoordinated “party” would occur if magnons are in a “thermal” state, while a coordinated one if they are in a “coherent” or “condensed” state. The coordinated movement of guests in the second type of party, on the other hand, would correspond to a superfluid flow, which is a manifestation of a remarkable state of matter: the condensate.

Read more