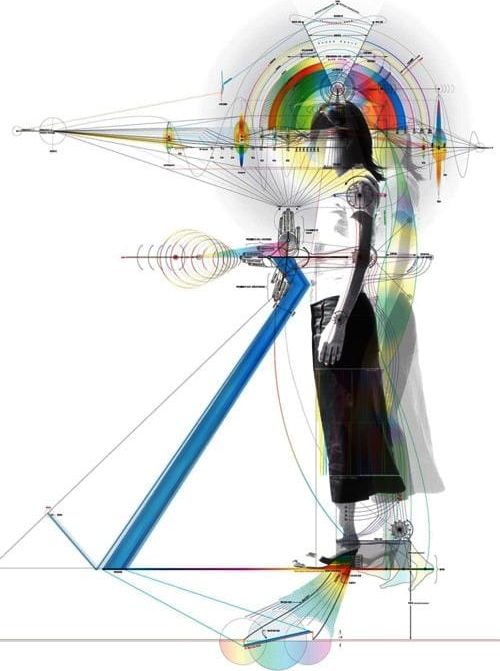

The double helix of dna and transferring for information and energy by torsion field in quantum beings.

Every human is a complex, multi-dimensional energy being.

THE HUMAN BIOFIELD DEFINED:

The human biofield is the energetic blueprint or matrix that creates the human form. Every human being, and every living creature on this planet, has such a blueprint. The human biofield is multidimensional, offering 3D physical form along with the vibrational aspects of the emotional and mental planes and beyond. The biofield is holographic and predetermines who we are, while at the same time reflects our state of being moment to moment. If any portion of the physical body is removed, the holographic blueprint of that tissue remains. The biofield can be read, scanned and interpreted in many different ways, just like any blueprint.