Make a donation to Closer To Truth to help us continue exploring the world’s deepest questions without the need for paywalls: https://shorturl.at/OnyRq.

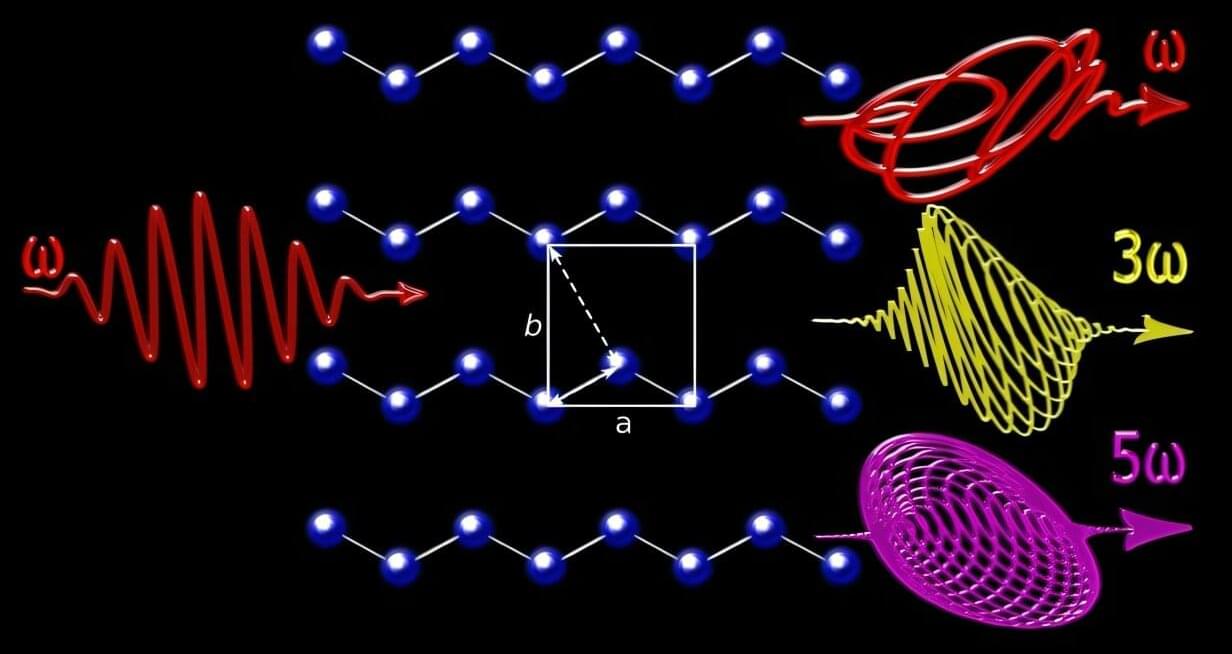

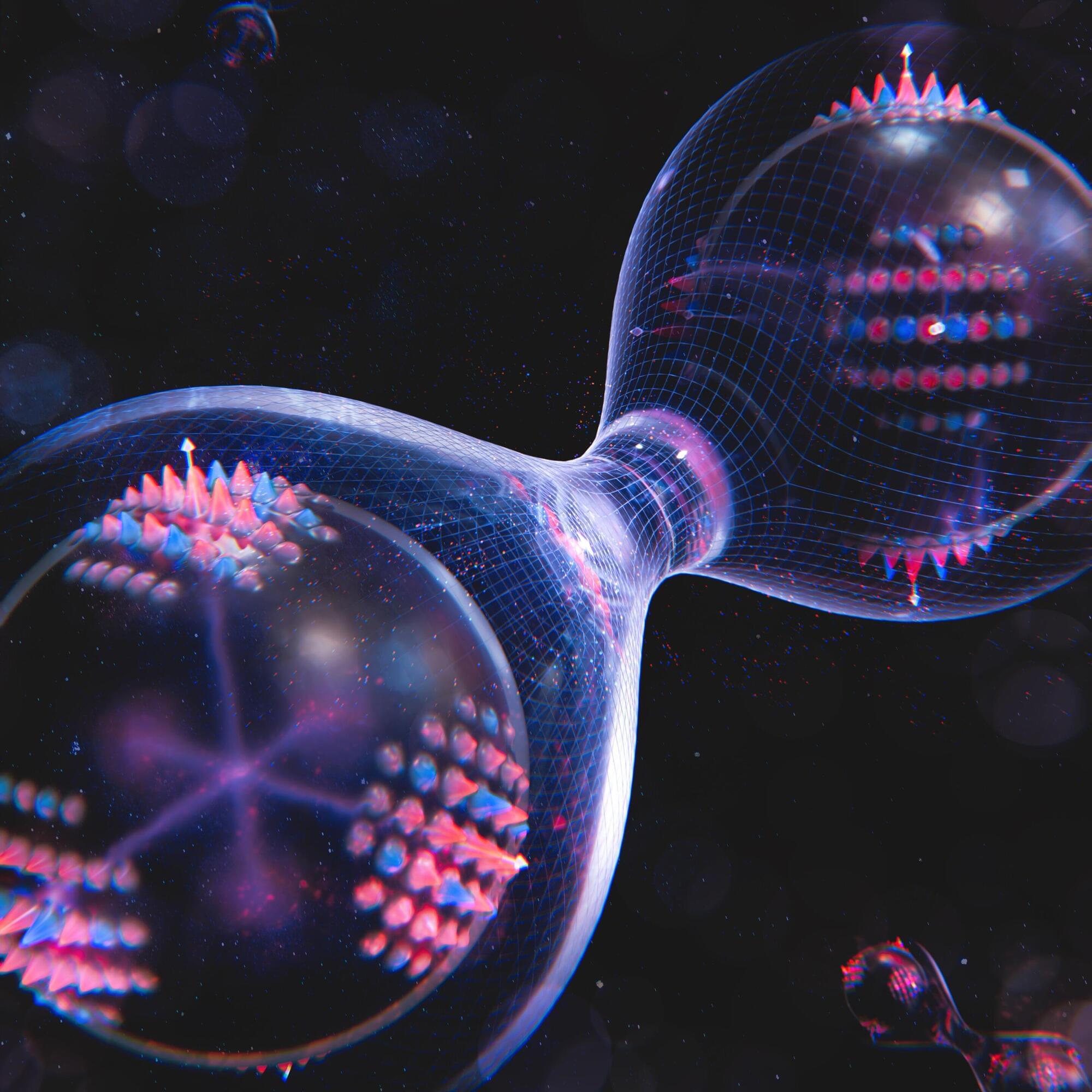

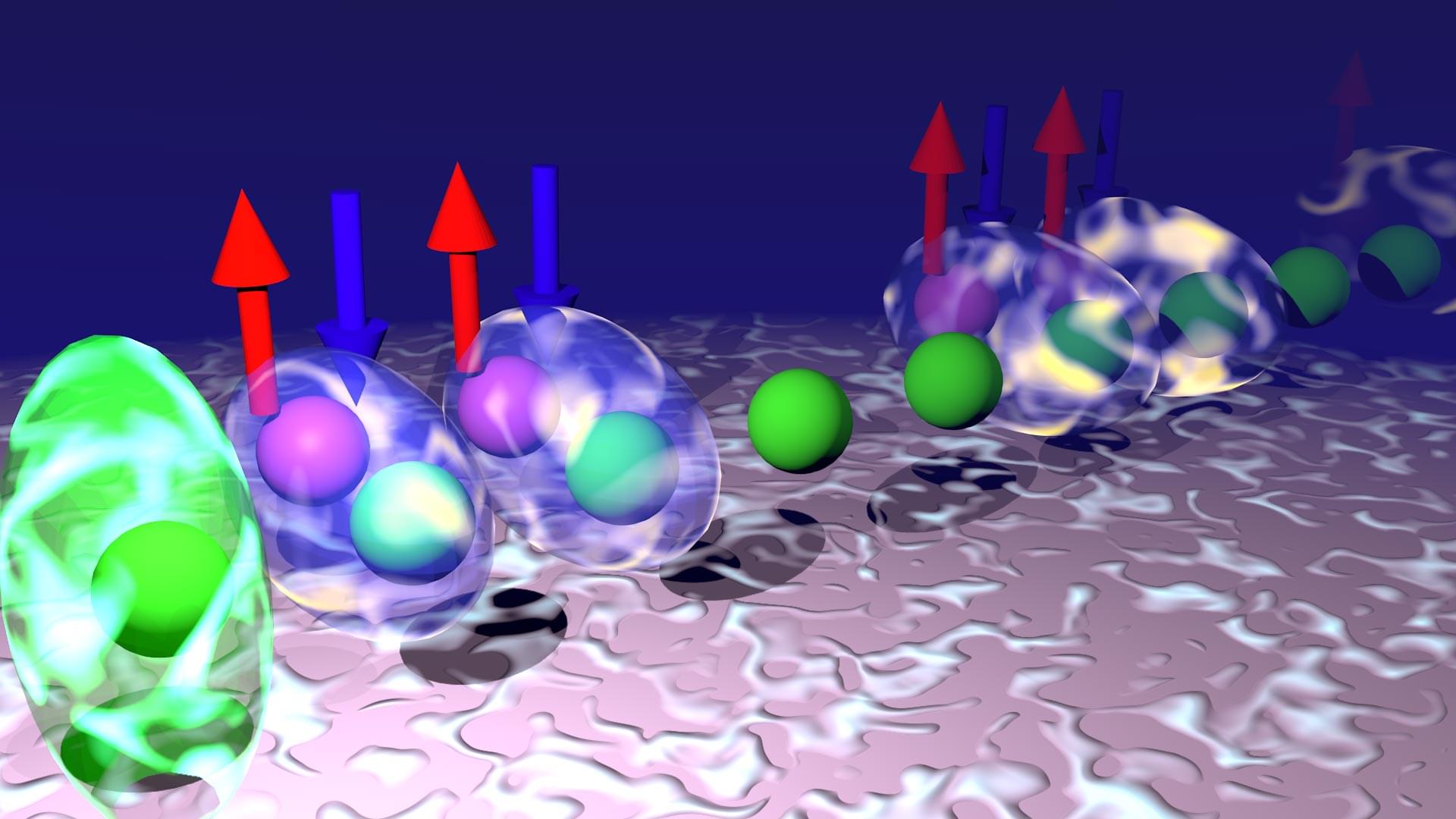

Quantum theory is very strange. No act is wholly sure. Everything works by probabilities, described by a wave function. But what is a wavefunction? One theory is that every possibility is in fact a real world of sorts. This is the Many Worlds interpretation of Hugh Everett and what it claims boggles the brain. You can’t imagine how many worlds there would be.

Free access to Closer to Truth’s library of 5,000 videos: http://bit.ly/376lkKN

Watch more interviews on quantum theory: https://bit.ly/3vQwB0f.

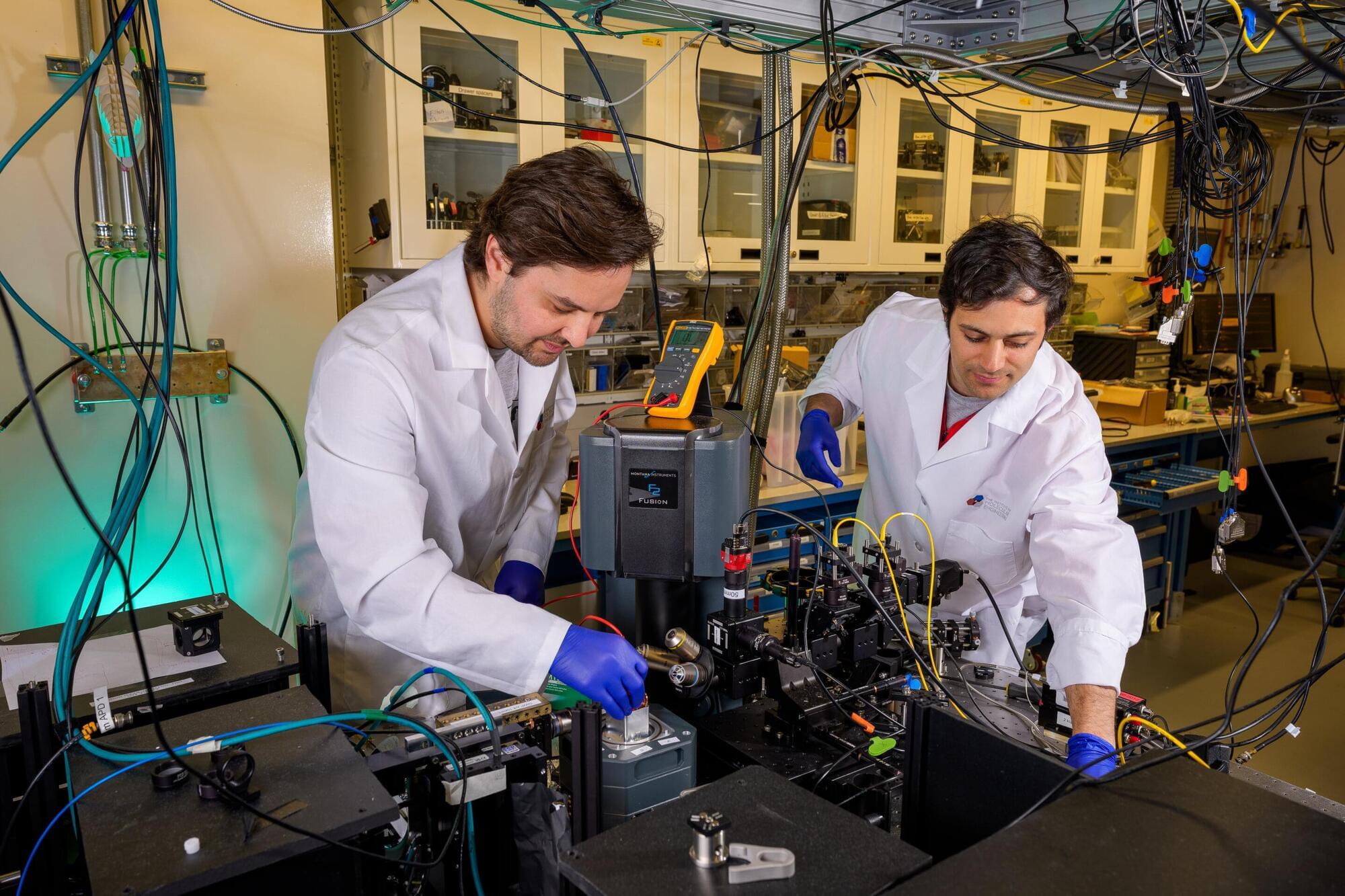

David Elieser Deutsch, FRS is a British physicist at the University of Oxford. He is a Visiting Professor in the Department of Atomic and Laser Physics at the Centre for Quantum Computation (CQC) in the Clarendon Laboratory of the University of Oxford.

Register for free at CTT.com for subscriber-only exclusives: http://bit.ly/2GXmFsP