A NASA X-ray spacecraft delivers new dimensions to the first images from the Webb telescope.

Images touch people in a way that words cannot. The unprecedented clarity of the Webb telescope’s first scientific images dazzled people across the world when they became public on July 12, 2022. Three months later, the team working on NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory released new images of the same target objects: Stephan’s Quintet, galaxy cluster SMACS 0723.3–7327, and the “Cosmic Cliffs” of the Carina Nebula. An image that Webb later took of the Cartwheel Galaxy also got an update. All these visuals add more “turbulent” information about these structures and give the originals a whole new dimension.

The full set of images is available here. To appreciate the new data, Inverse set some of them side by side with their corresponding original image.

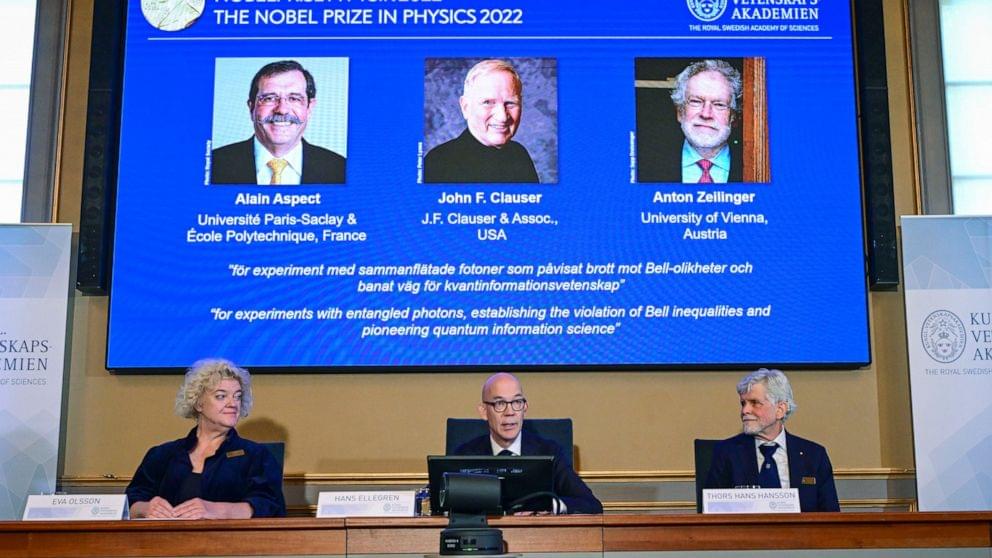

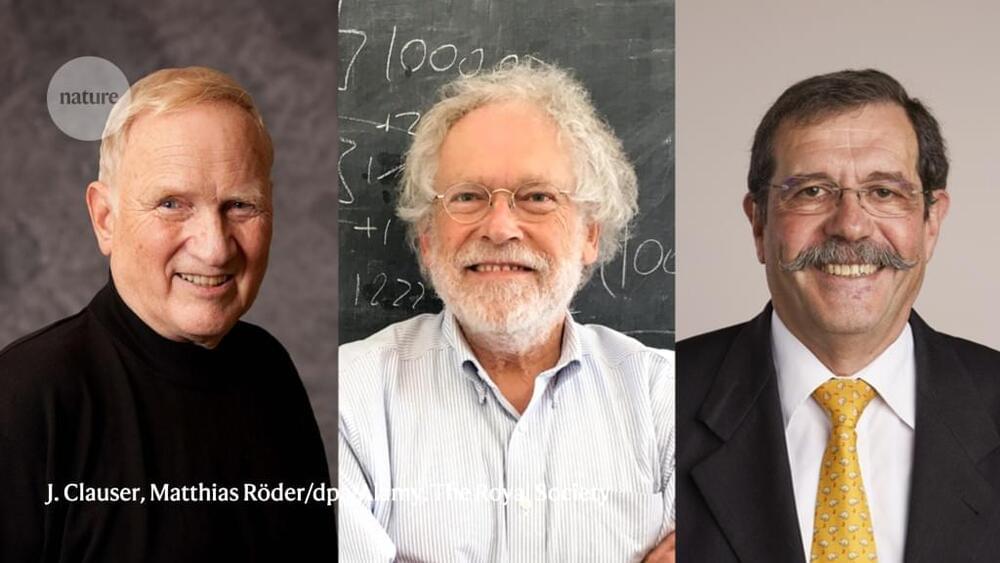

Chandra launched in 1999 and is named after Indian-American Nobel laureate Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. The new images became public the same day the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics, which highlighted achievements in quantum entanglement, were announced, coincidentally.