The Nobel Prize in physics this year has been awarded “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science”.

The Nobel Prize in physics this year has been awarded “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science”.

Sponsor: AG1, The nutritional drink I’m taking for energy and mental focus. Tap this link to get a year’s supply of immune-supporting vitamin D3-K2 & 5 travel packs FREE with your first order: https://www.athleticgreens.com/arvinash.

Science Asylum video on Schrodinger Equation:

JOIN our PATREON (Members help pay for the animations. THANK YOU so much!):

https://www.patreon.com/arvinash.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Schwartz, “Quantum Field Theory and the Standard model” https://amzn.to/3HmWdYt.

CHAPTERS:

0:00 The most important motion in the universe.

1:08 How get energy and mental focus.

2:20 A spring: Classical simple harmonic oscillator.

4:48 QUANTUM Harmonic oscillator.

6:00 Science Asylum — what is the Schrodinger equation?

7:30 Quantum Field Theory (QFT) uses spring math!

10:00 Intuitive description of what’s going on!

12:37 What is really oscillating in QFT?

SUMMARY:

Astonishing lecture Leonard Susskind.

Proof that ER=EPR.

Renowned physicist Neil Turok, Holder of the Higgs Chair of Theoretical Physics at the University of Edinburgh, joins me to discuss the state of science and the universe. is Physics in trouble? What hope is there to return to more productive and Simple theories? What is Peter Higgs up to?

Neil Turok has been director emeritus of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics since 2019. He specializes in mathematical physics and early-universe physics, including the cosmological constant and a cyclic model for the universe.

He has written several books including Endless Universe: Beyond the Big Bang and The Universe Within: From Quantum to Cosmos.

00:00:00 Intro.

00:03:28 What is the meaning of Neil’s book cover?

00:06:46 The Nature of the Endless Universe.

00:14:31 What would happen to James Clerk Maxwell and Michael Faraday on Twitter?

00:16:10 What’s wrong with physics today?

00:20:06 How did Neil’s life change after his theory was proven wrong?

00:23:28 Neil shows us fundamental laws of the Universe in equations.

00:33:59 How well do our modern equations satisfy the conditions of the observable Universe?

00:56:29 How is the Universe simple?

01:20:01 Can Neil’s model explain flatness without inflation?

01:54:54 Existential Questions on the meaning of life, advice to his former self, and things he’s changed his mind on.

Join this channel to get access to perks:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCmXH_moPhfkqCk6S3b9RWuw/join.

📺 Watch my most popular videos:📺

Researchers have theorized a new mechanism to generate high-energy “quantum light,” which could be used to investigate new properties of matter at the atomic scale.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, along with colleagues from the U.S., Israel and Austria, developed a theory describing a new state of light, which has controllable quantum properties over a broad range of frequencies, up as high as X-ray frequencies. Their results are reported in the journal Nature Physics.

The world we observe around us can be described according to the laws of classical physics, but once we observe things at an atomic scale, the strange world of quantum physics takes over. Imagine a basketball: observing it with the naked eye, the basketball behaves according to the laws of classical physics. But the atoms that make up the basketball behave according to quantum physics instead.

Do you want to know whether a very large integer is a prime number or not? Or if it is a “lucky number”? A new study by SISSA, carried out in collaboration with the University of Trieste and the University of Saint Andrews, suggests an innovative method that could help answer such questions through physics, using some sort of “quantum abacus.”

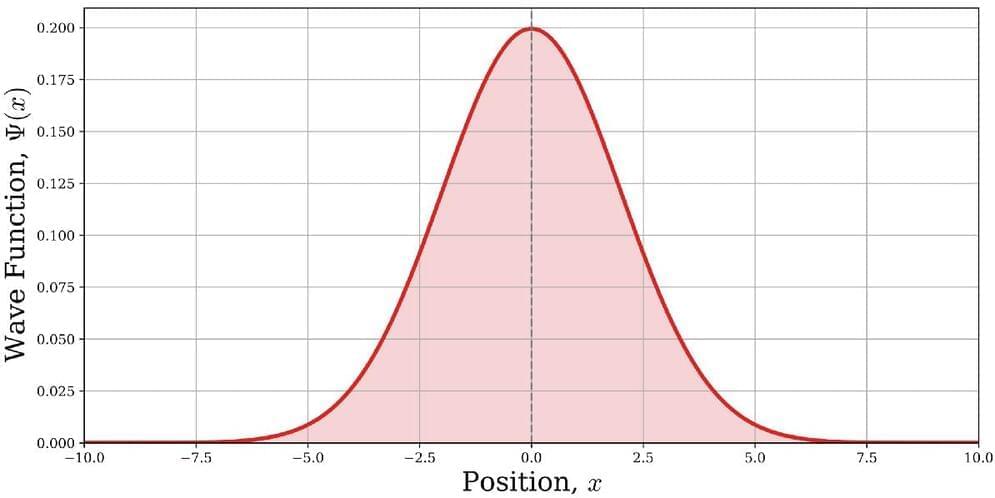

By combining theoretical and experimental work, scientists were able to reproduce a quantum potential with energy levels corresponding to the first 15 prime numbers and the first 10 lucky numbers using holographic laser techniques. This result, published in PNAS Nexus, opens the door to obtaining potentials with finite sequences of integers as arbitrary quantum energies, and to addressing mathematical questions related to number theory with quantum mechanical experiments.

“Every physical system is characterized by a certain set of energy levels, which basically make up its ID,” explains Giuseppe Mussardo, theoretical physicist at SISSA—International School for Advanced Studies. “In this work, we have reversed this line of reasoning: is it possible—starting from an arithmetic sequence, for example that of prime numbers—to obtain a quantum system with those very numbers as energy levels?”

Physicists using advanced muon spin spectroscopy at Paul Scherrer Institute PSI found the missing link between their recent breakthrough in a kagome metal and unconventional superconductivity. The team uncovered an unconventional superconductivity that can be tuned with pressure, giving exciting potential for engineering quantum materials.

A year ago, a group of physicists led by PSI detected evidence of an unusual collective electron behavior in a kagome metal, known as time-reversal symmetry-breaking charge order—a discovery that was published in Nature.

Although this type of behavior can hint towards the highly desirable trait of unconventional superconductivity, actual evidence that the material exhibited unconventional superconductivity was lacking. Now, in a new study published in Nature Communications, the team have provided key evidence to make the link between the unusual charge order they observed and unconventional superconductivity.

Trapped ions have previously only been entangled in one and the same laboratory. Now, teams led by Tracy Northup and Ben Lanyon from the University of Innsbruck have entangled two ions over a distance of 230 meters.

The nodes of this network were housed in two labs at the Campus Technik to the west of Innsbruck, Austria. The experiment shows that trapped ions are a promising platform for future quantum networks that span cities and eventually continents.

Trapped ions are one of the leading systems to build quantum computers and other quantum technologies. To link multiple such quantum systems, interfaces are needed through which the quantum information can be transmitted.

Start using AnyDesk, the blazing-fast Remote Desktop Software, today at https://anydesk.com/en/downloads/windows?utm_source=brand&am…tm_term=en.

Written by Joseph Conlon.

Professor of Theoretical Physics, University of Oxford.

Author, Why String Theory? https://www.amazon.com/Why-String-Theory-Joseph-Conlon/dp/14…atfound-20

Edited and Narrated by David Kelly.

Thumbnail Art by Ettore Mazza.

Animations by Jero Squartini https://fiverr.com/freelancers/jerosq.

Huge thanks to Jeff Bryant for his Calabi-yau animation.

Footage from Videoblocks, Artlist. Footage of galaxies from NASA and ESO.

Music from Epidemic Sound, Artlist, Silver Maple and Yehezkel Raz.

Image Credits:

NRAO Edward Witten.

Paul, Dirac photo By Science Museum London / Science and Society Picture Library — The physicists Paul Dirac, Wolfgang Pauli and Rudolf Peierls, c 1953.Uploaded by Mrjohncummings, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28024324