Researchers have put a sapphire crystal containing quadrillions of atoms into a superposition of quantum states, bringing quantum effects into the macroscopic world.

By Leah Crane

Researchers have put a sapphire crystal containing quadrillions of atoms into a superposition of quantum states, bringing quantum effects into the macroscopic world.

By Leah Crane

Playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLnK6MrIqGXsJfcBdppW3CKJ858zR8P4eP

Download PowerPoint: https://github.com/hywong2/Intro_to_Quantum_Computing.

Book (Free with institution subscription): https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-98339-0

Book: https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Quantum-Computing-Layper…atfound-20

Can quantum computing replace classical computing? State, Superposition, Measurement, Entanglement, Qubit Implementation, No-cloning Theorem, Error Correction, Caveats.

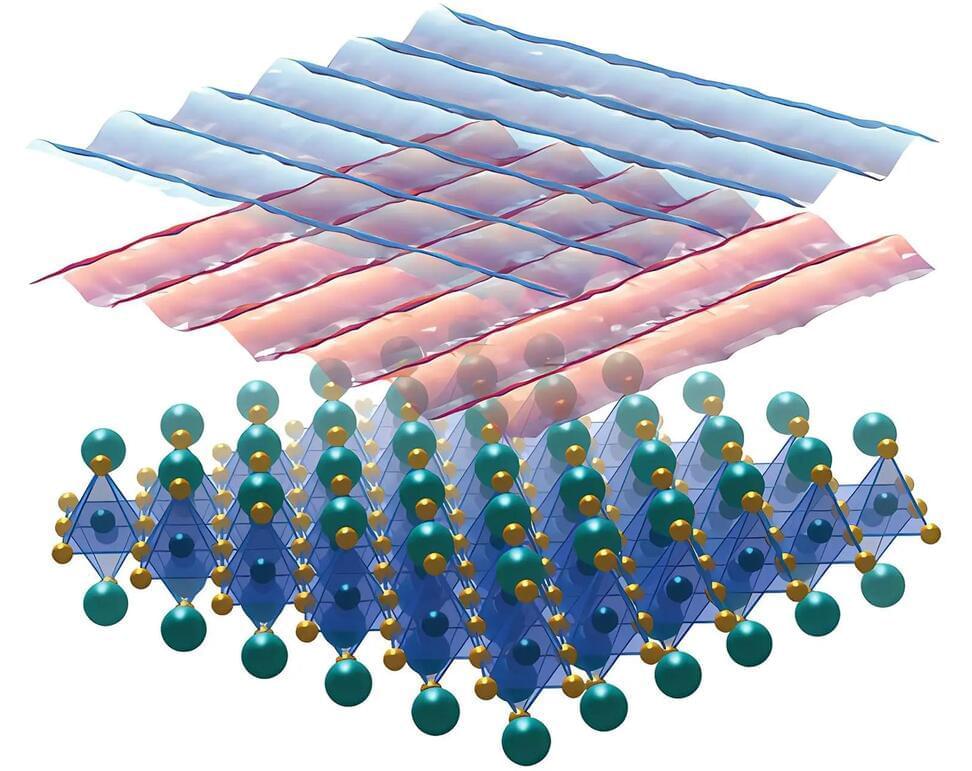

Hidden stripes in a crystal could help scientists understand the mysterious behavior of electrons in certain quantum systems, including high-temperature superconductors, an unexpected discovery by RIKEN physicists suggests.

The electrons in most materials interact with each other very weakly. But physicists often observe interesting properties in materials in which electrons strongly interact with each other. In these materials, the electrons often collectively behave as particles, giving rise to ‘quasiparticles’.

“A crystal can be thought of like an alternative universe with different laws of physics that allow different fundamental particles to live there,” says Christopher Butler of the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science.

Ludovico Lami of QuSoft and the University of Amsterdam and Mark M. Wilde of Cornell have achieved a major breakthrough in the field of quantum computing by developing a formula that predicts the impact of environmental noise. This formula is critical in the creation of quantum computers that can wo.

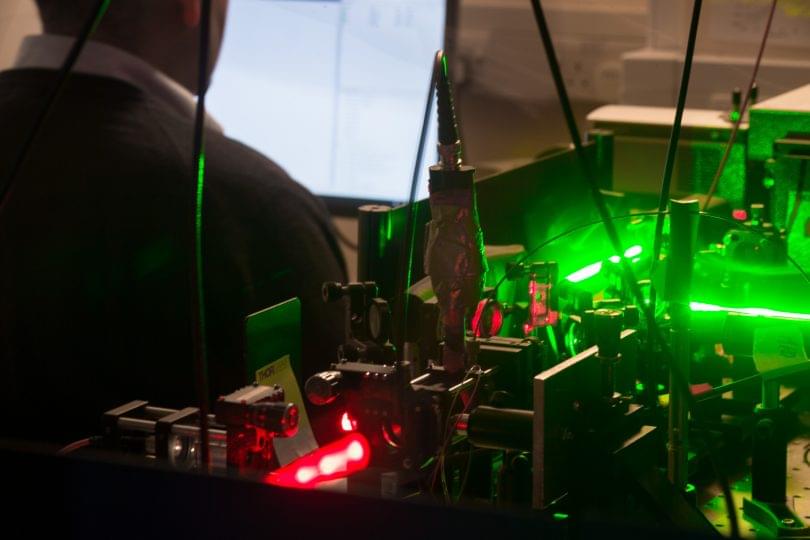

The Oxford Martin Programme on Bio-Inspired Technologies is investigating the possibility of making computers real.

We aim to develop a completely new methodology for overcoming the extreme fragility of memory. By learning how biological molecules shield fragile states from the environment, we hope to create the building blocks of future computers.

The unique power of computers comes from their ability to carry out all possible calculations in parallel.

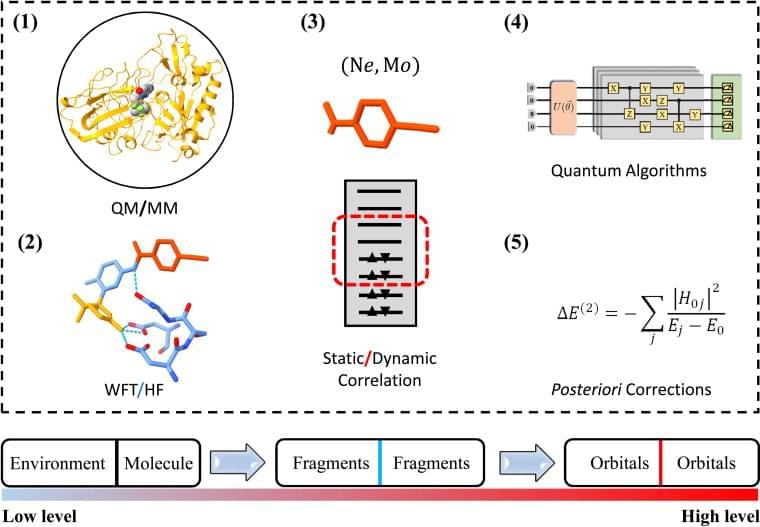

As quantum advantage has been demonstrated on different quantum computing platforms using Gaussian boson sampling,1–3 quantum computing is moving to the next stage, namely demonstrating quantum advantage in solving practical problems. Two typical problems of this kind are computational-aided material design and drug discovery, in which quantum chemistry plays a critical role in answering questions such as ∼Which one is the best?∼. Many recent efforts have been devoted to the development of advanced quantum algorithms for solving quantum chemistry problems on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices,2,4–14 while implementing these algorithms for complex problems is limited by available qubit counts, coherence time and gate fidelity. Specifically, without error correction, quantum simulations of quantum chemistry are viable only if low-depth quantum algorithms are implemented to suppress the total error rate. Recent advances in error mitigation techniques enable us to model many-electron problems with a dozen qubits and tens of circuit depths on NISQ devices,9 while such circuit sizes and depths are still a long way from practical applications.

The difference between the available and actually required quantum resources in practical quantum simulations has renewed the interest in divide and conquer (DC) based methods.15–19 Realistic material and (bio)chemistry systems often involve complex environments, such as surfaces and interfaces. To model these systems, the Schrödinger equations are much too complicated to be solvable. It therefore becomes desirable that approximate practical methods of applying quantum mechanics be developed.20 One popular scheme is to divide the complex problem under consideration into as many parts as possible until these become simple enough for an adequate solution, namely the philosophy of DC.21 The DC method is particularly suitable for NISQ devices since the sub-problem for each part can in principle be solved with fewer computational resources.15–18,22–25 One successful application of DC is to estimate the ground-state potential energy surface of a ring containing 10 hydrogen atoms using the density matrix embedding theory (DMET) on a trapped-ion quantum computer, in which a 20-qubit problem is decomposed into ten 2-qubit problems.18

DC often treats all subsystems at the same computational level and estimates physical observables by summing up the corresponding quantities of subsystems, while in practical simulations of complex systems, the particle–particle interactions may exhibit completely different characteristics in and between subsystems. Long-range Coulomb interactions can be well approximated as quasiclassical electrostatic interactions since empirical methods, such as empirical force filed (EFF) approaches,26 are promising to describe these interactions. As the distance between particles decreases, the repulsive exchange interactions from electrons having the same spin become important so that quantum mean-field approaches, such as Hartree–Fock (HF), are necessary to characterize these electronic interactions.

Quantum networking uses subatomic matter to deliver data in a way that goes beyond today’s fiber-optic systems. Amazon wants to grow diamonds which would be part of a component that lets the data travel farther without breaking down.

Pretty futuristic!

Amazon.com Inc. is teaming up with a unit of De Beers Group to grow artificial diamonds, betting that custom-made gems could could help revolutionize computer networks.

The human brain, with its intricate networks of neurons, has long been a subject of fascination and mystery. Concurrently, the cosmos, with its vastness and complexity, has intrigued scientists and philosophers for centuries.

Recent research has begun to explore the possibility that the brain and the cosmos might be connected on a quantum scale. This article will delve into the research paper titled “Quantum transport in fractal networks” and discuss its implications for our understanding of the relationship between the brain and the cosmos.

Many experts in the industry predict the cost of quantum computing hardware will continue to decrease over time as the technology advances, making it more accessible to a broader range of businesses and organizations. In a recent talk, the CTO of the CIA Nand Mulchandani noted that the quantum industry is still very early and unit costs are still very high, as we are very much in the research and development stage.

In general, pricing concerns are sure to be influenced by several important factors, including how advanced discoveries in the sector are made, market demand for the technology and competition among quantum computing providers.

The Quantum Insider observes with a keen eye the market trends and technological narrative that is evolving as we speak. When thinking about the price of a quantum computer price in 2023, it’s worth considering the access method, the type of computer and usage requirements.