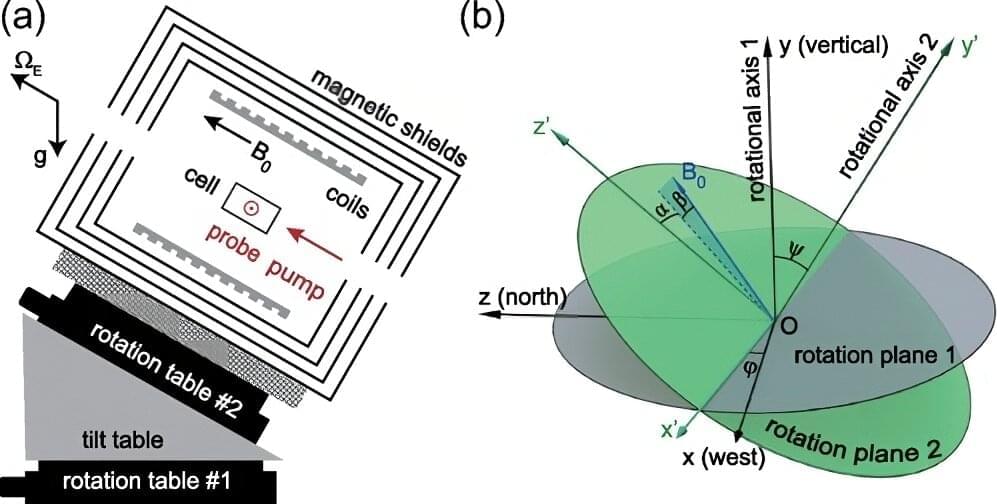

A joint research group led by Prof. Sheng Dong and Prof. Lu Zhengtian from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), investigated the coupling effect between neutron spin and gravitational force via employing a high-precision xenon isotope magnetometer. This work was published in Physical Review Letters.

This research aims to uncover the coupling strength between neutron spin and gravity by measuring the weight difference between the neutron’s spin-up and spin-down states. The experimental results revealed that the weight difference between these two states was less than two sextillionths (2×10-21), setting a new upper limit on the coupling strength of this effect.

An article titled “Testing Gravity’s Effect on Quantum Spins,” reported in Physics, highlights this precise measurement research as a novel exploration of the intersection of quantum theory and gravity.