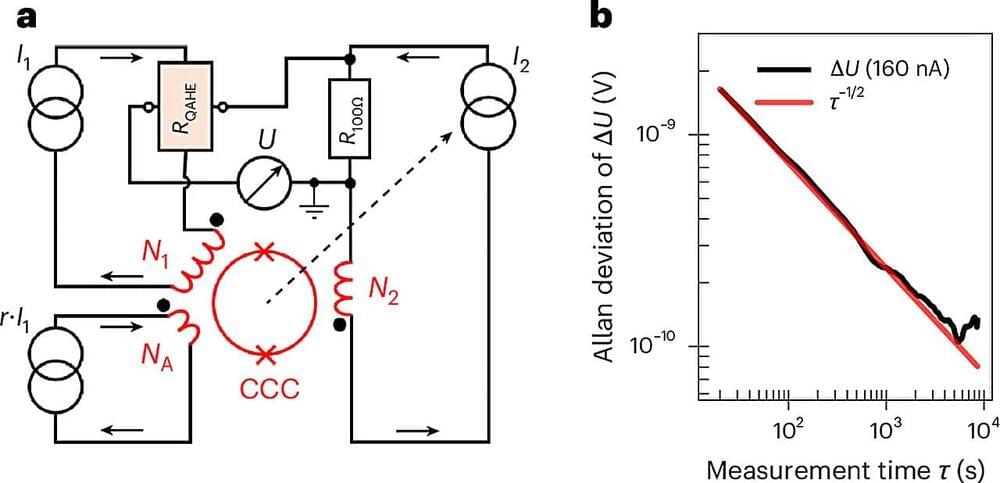

Scientists at the University of Würzburg and the German national metrology institute (PTB) have carried out an experiment that realizes a new kind of quantum standard of resistance. It’s based on the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect.

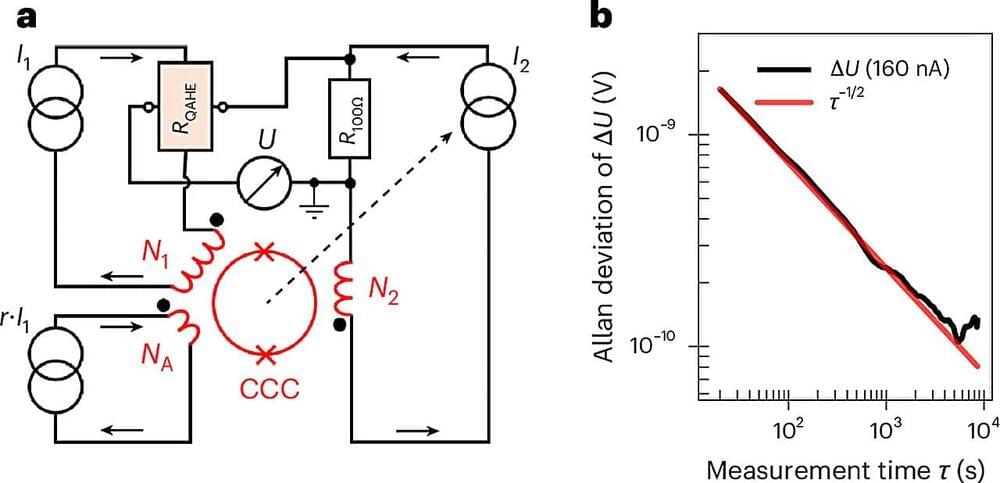

Researchers have shown that optical spring tracking is a promising way to improve the signal clarity of gravitational-wave detectors. The advance could one day allow scientists to see farther into the universe and provide more information about how black holes and neutron stars behave as they merge.

Large-scale interferometers such as the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (aLIGO) detect subtle distortions in spacetime, known as gravitational waves, generated by distant cosmic events. By allowing scientists to study phenomena that do not emit light, gravitational wave measurements have opened a new window for understanding extreme astrophysical events, the nature of gravity and the origins of the universe.

“Quantum noise has become a limiting noise source when measuring gravitational waves,” said Scott M. Aronson, a member of the research team from Louisiana State University. “By tuning the system to respond at a desired frequency, we show that you can reduce this noise by using an optical spring to track a signal coming from a compact binary system. In the future, this binary system could be two black holes orbiting each other—within our galaxy or beyond.”

French physicist Louis de Broglie’s pilot wave theory proposed that quantum particles are directed by a guiding wave. Although de Broglie later renounced his theory due to its complexity and abstractness, the concept was revived by David Bohm and remains a topic of ongoing scientific exploration and debate.

Celebrating a Century of Quantum Discovery

Last week marked the 100-year anniversary of French physicist Louis de Broglie presenting his doctoral thesis, a groundbreaking work that earned him a Nobel prize for “his discovery of the wave nature of electrons.” His discovery became a cornerstone of quantum mechanics and gave rise to his renowned “pilot wave” theory—an alternative framework for understanding the quantum world. Yet, despite its significance, de Broglie later rejected his own theory. Why did he abandon it?

Quantum chaos, previously theoretical, has been observed experimentally, validating a 40-year-old theory about electrons forming patterns in confined spaces.

Using advanced imaging techniques on graphene, researchers confirmed “quantum scars,” where electrons follow unique closed orbits. These findings could revolutionize electronics by enabling efficient, low-power transistors and paving the way for novel quantum control methods. This discovery offers insights into chaotic quantum systems, bridging a gap between classical and quantum physics.

Patterns in chaos revealed in quantum space.

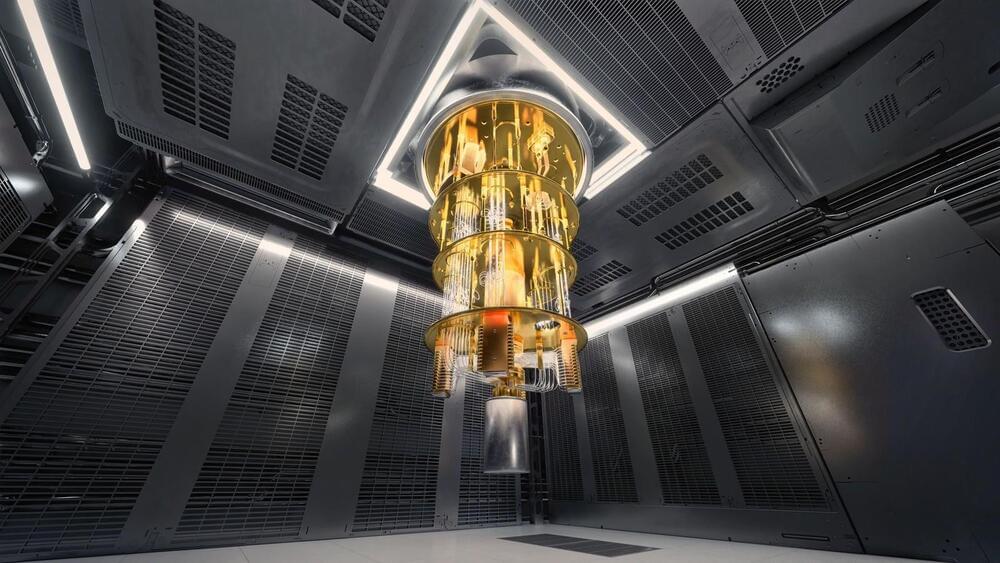

Each quantum computing trajectory faces unique developmental needs. Gate-based quantum computers require scalability, error correction and quantum gate fidelity improvements to achieve stable, accurate computations. The whole-systems approach needs advances in qubit connectivity and reductions in noise interference to boost computational reliability. Meanwhile, parsing-of-totality depends on advancing sensing techniques to harness atoms’ deeper patterns and potentiality.

Major investments are currently directed toward gate-based quantum computing, with IBM, Google and Microsoft leading the charge, aiming for universal quantum computation. However, the idea of universal quantum computation remains complex given that the parsing-of-totality approach suggests the possibility of new quantum patterns, properties and even principles that could require a conceptual shift as radical as the transition from classical bits to quantum qubits.

All three trajectories will play essential roles in the future of quantum computing. Gate-based systems may ultimately achieve universal applicability. Whole-systems quantum computing will continue to reframe a larger class of problems as complex adaptive systems requiring optimization to be solved. The parsing-based approaches will leverage novel quantum principles to spawn new quantum technologies.

This study focuses on topological time crystals, which sort of take this idea and make it a bit more complex (not that it wasn’t already). A topological time crystal’s behavior is determined by overall structure, rather than just a single atom or interaction. As ZME Science describes, if normal time crystals are a strand in a spider’s web, a topological time crystal is the entire web, and even the change of a single thread can affect the whole web. This “network” of connection is a feature, not a flaw, as it makes the topological crystal more resilient to disturbances—something quantum computers could definitely put to use.

In this experiment, scientists essentially embedded this behavior into a quantum computer, creating fidelities that exceeded previous quantum experiments. And although this all occurred in a prethermal regime, according to ZME Science, it’s still a big step forward towards potentially creating a more stable quantum computer capable of finally unlocking that future that always feels a decade from our grasp.

The integration of quantum computing into personalized medicine holds great promise for revolutionizing disease diagnosis, treatment development, and patient outcomes. Quantum computers have the potential to process vast amounts of genetic data much faster than classical computers, enabling researchers to identify patterns and correlations that may not be apparent with current technology. This could lead to breakthroughs in understanding the genetic basis of complex diseases and developing targeted treatments.

Quantum computing also has the potential to revolutionize medical imaging by enabling the simulation of complex magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Quantum algorithms can efficiently process large-scale imaging data, enabling researchers to reconstruct high-resolution images that reveal subtle details about tissue structure and function. This has significant implications for disease diagnosis and treatment, where accurate imaging is critical for developing effective treatments.

The use of quantum computing in personalized medicine raises important ethical considerations, such as concerns about privacy and informed consent. The ability to rapidly analyze large amounts of genetic data also raises questions about how this information should be used and shared with patients. Regulatory frameworks will play a crucial role in shaping the development and deployment of quantum computing in personalized medicine, balancing the need to promote innovation with the need to protect patient safety and privacy.

What do motion detectors, self-driving cars, chemical analyzers and satellites have in common? They all contain detectors for infrared (IR) light. At their core and besides readout electronics, such detectors usually consist of a crystalline semiconductor material.

Such materials are challenging to manufacture: They often require extreme conditions, such as a very high temperature, and a lot of energy. Empa researchers are convinced that there is an easier way. A team led by Ivan Shorubalko from the Transport at the Nanoscale Interfaces laboratory is working on miniaturized IR detectors made of colloidal quantum dots.

The words “quantum dots” do not sound like an easy concept to most people. Shorubalko explains, “The properties of a material depend not only on its chemical composition, but also on its dimensions.” If you produce tiny particles of a certain material, they may have different properties than larger pieces of the very same material. This is due to quantum effects, hence the name “quantum dots.”

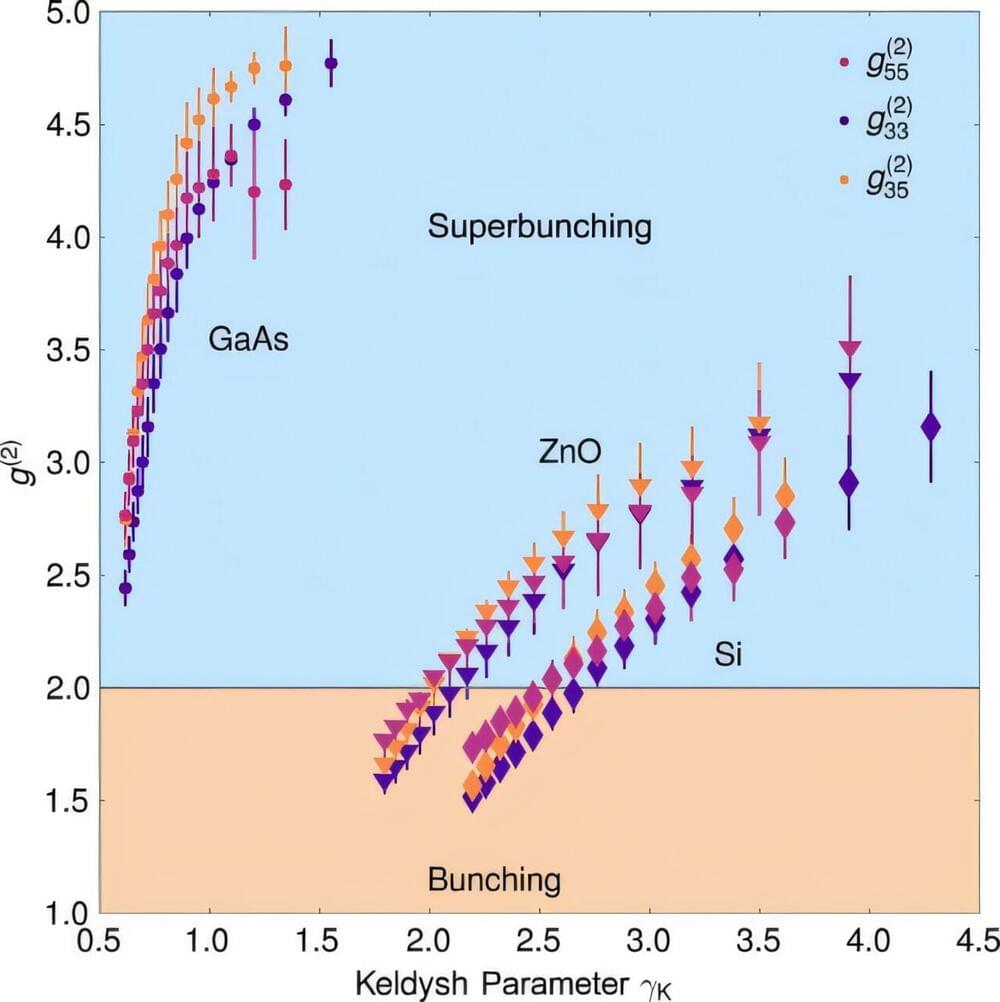

High harmonic generation (HHG) is a highly non-linear phenomenon where a system (for example, an atom) absorbs many photons of a laser and emits photons of much higher energy, whose frequency is a harmonic (that is, a multiple) of the incoming laser’s frequency. Historically, the theoretical description of this process was addressed from a semi-classical perspective, which treated matter (the electrons of the atoms) quantum-mechanically, but the incoming light classically. According to this approach, the emitted photons should also behave classically.

Despite this evident theoretical mismatch, the description was sufficient to carry out most of the experiments, and there was no apparent need to change the framework. Only in the last few years has the scientific community begun to explore whether the emitted light could actually exhibit a quantum behavior, which the semi-classical theory might have overlooked. Several theoretical groups, including the Quantum Optics Theory group at ICFO, have already shown that, under a full quantum description, the HHG process emits light with quantum features.

However, experimental validation of such predictions remained elusive until, recently, a team led by the Laboratoire d’Optique Appliquée (CNRS), in collaboration with ICREA Professor at ICFO Jens Biegert and other multiple institutions (Institut für Quantenoptik—Leibniz Universität Hannover, Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Optics and Precision Engineering IOF, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena), demonstrated the quantum optical properties of high-harmonic generation in semiconductors. The results, appearing in PRX Quantum, align with the previous theoretical predictions about HHG.