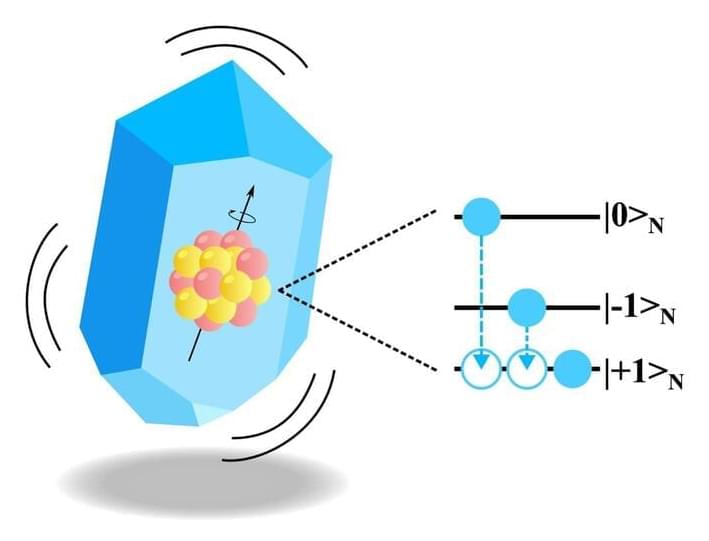

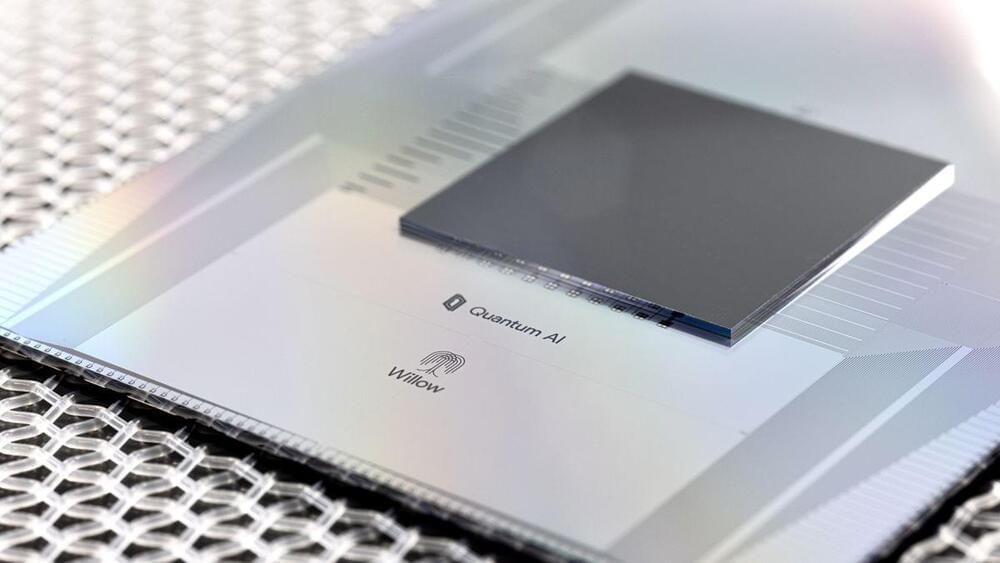

In the world of science, even a small twist may carry immense implications for materials. Researchers at City University of Hong Kong have uncovered how a subtle rotation in 2D layers can give rise to a vortex electric field. This finding, published in Science, has the potential to impact electronic, magnetic, and optical devices as well as new applications in quantum computing, spintronics, and nanotechnology. According to Professor Ly Thuc Hue of CityUHK’s Department of Chemistry, the study demonstrates how “a simple twist in bilayer 2D materials” can induce this electric field, bypassing the need for costly thin-film deposition techniques.

Akin to solving intricate technical puzzles, researchers had to ensure clean, precisely aligned layers of material—a notoriously difficult challenge in the world of 2D materials. Twisted bilayers are made by stacking two thin layers of a material at a slight angle, creating unique electronic properties.

However, traditional methods of synthesizing these bilayers often limit the range of twist angles, particularly at smaller degrees, making exploration of their full potential nearly impossible. To address this, the team at City University of Hong Kong developed an ice-assisted transfer technique that uses a thin sheet of ice to align and transfer bilayers with precision.