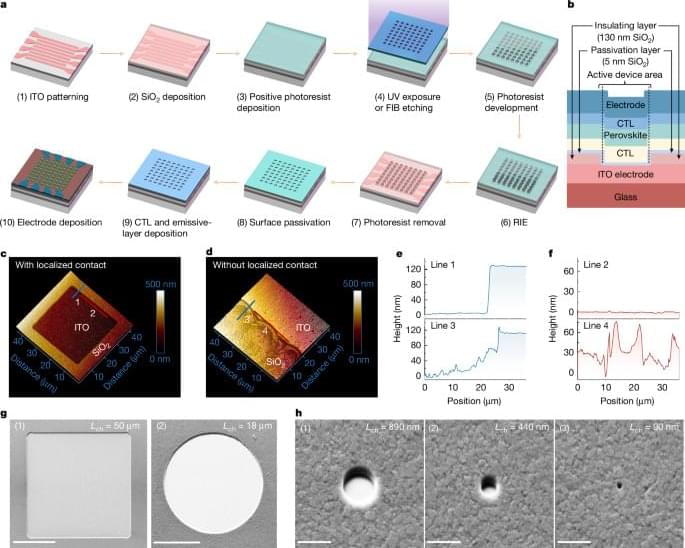

A process based on perovskite semiconductors is described to downscale micro-LEDs and nano-LEDs to below the conventional size limits, demonstrating average external quantum efficiencies maintained at around 20% across a wide range of pixel lengths.

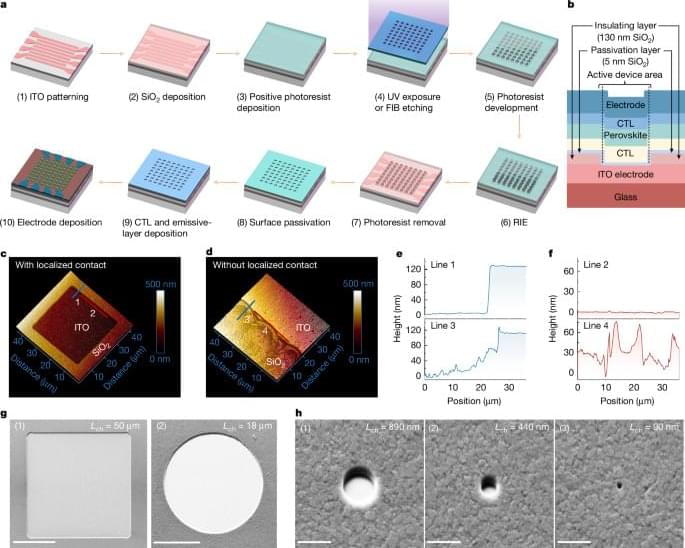

A research team led by Professor Sun Qing-Feng in collaboration with Professor He Lin’s research group from Beijing Normal University has achieved orbital hybridization in graphene-based artificial atoms for the first time.

Their study, titled “Orbital hybridization in graphene-based artificial atoms” has been published in Nature. The work marks a significant milestone in the field of quantum physics and materials science, bridging the gap between artificial and real atomic behaviors.

Quantum dots, often called artificial atoms, can mimic atomic orbitals but have not yet been used to simulate orbital hybridization, a crucial process in real atoms. While quantum dots have successfully demonstrated artificial bonding and antibonding states, their ability to replicate orbital hybridization remained unexplored.

A new type of time crystal could represent a breakthrough in quantum physics.

In a diamond zapped with lasers, physicists have created what they believe to be the first true example of a time quasicrystal – one in which patterns in time are structured, but do not repeat. It’s a fine distinction, but one that could help evolve quantum research and technology.

“They could store quantum memory over long periods of time, essentially like a quantum analog of RAM,” says physicist Chong Zu of Washington University in the US. “We’re a long way from that sort of technology. But creating a time quasicrystal is a crucial first step.”

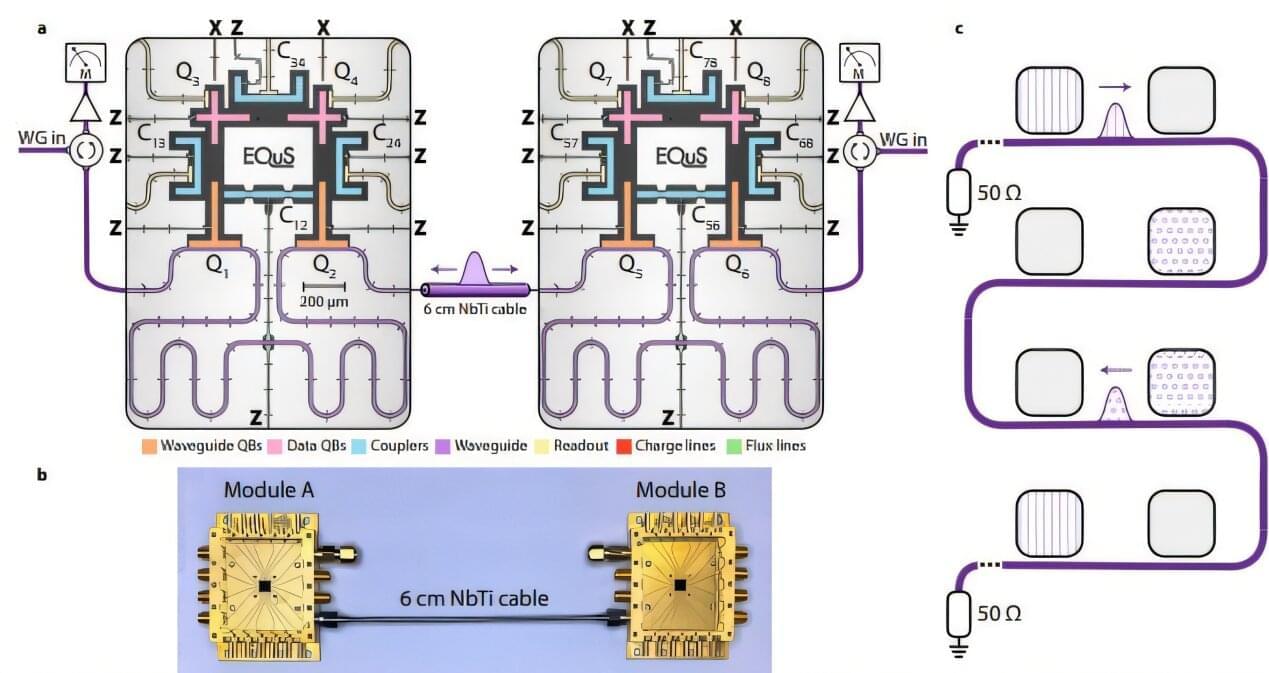

Quantum computers, devices that process information leveraging quantum mechanical effects, could outperform classical computers in some complex optimization and computational tasks. However, before these systems can be adopted on a large-scale, some technical challenges will need to be overcome.

One of these challenges is the effective connection of qubits, which operate at cryogenic temperatures, with external controllers that operate at higher temperatures. Existing methods to connect these components rely on coaxial cables or optical interconnects, both of which are not ideal as they introduce excessive heat and noise.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) recently set out to overcome the limitations of these approaches for connecting qubits and controllers, addressing common complaints about existing connecting cables. Their paper, published in Nature Electronics, introduces a new wireless terahertz (THz) cryogenic interconnect based on complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology, which was found to minimize heat in quantum processors while effectively transferring quantum information.

Quantum computers have the potential to solve complex problems that would be impossible for the most powerful classical supercomputer to crack.

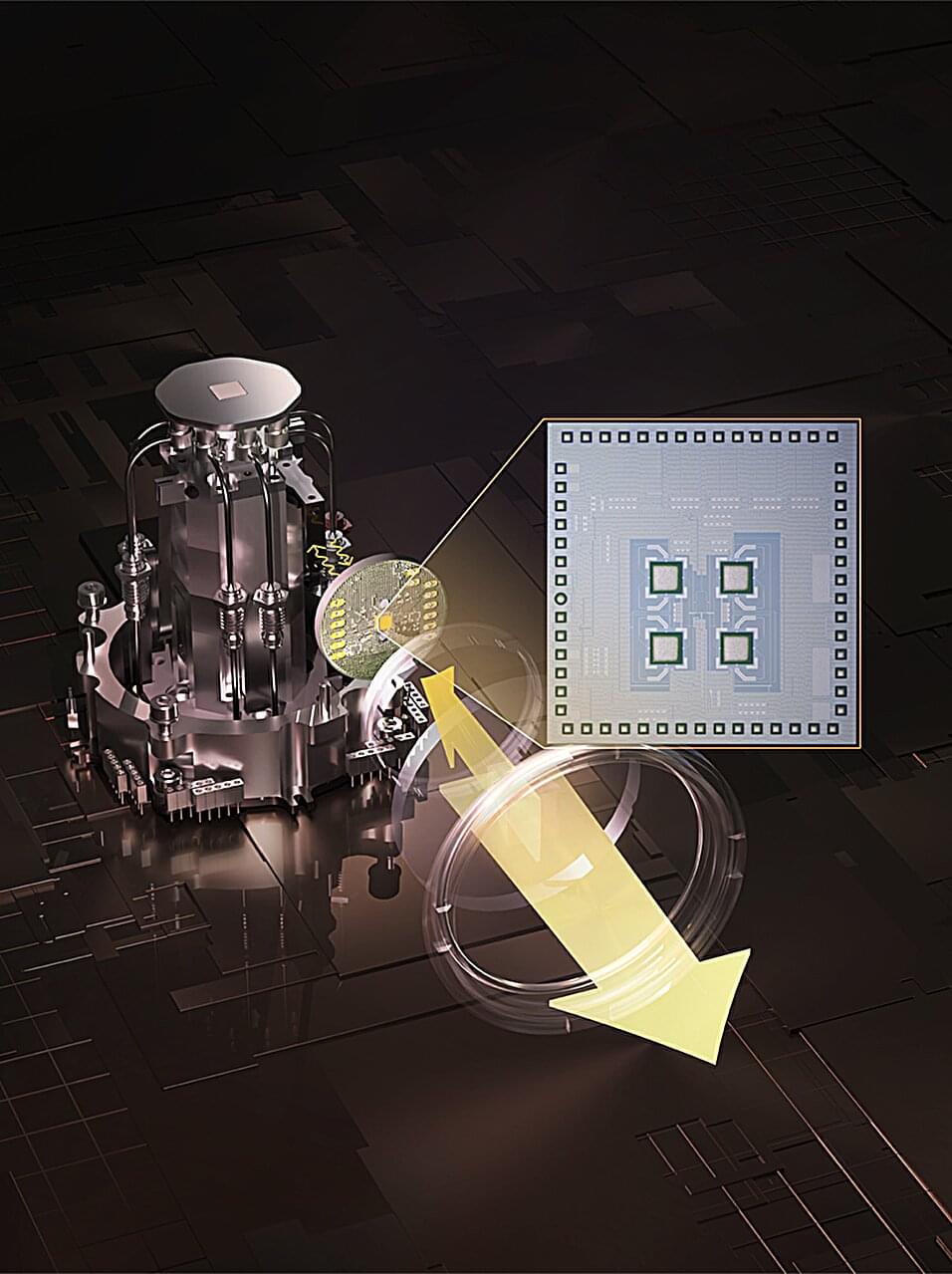

Just like a classical computer has separate yet interconnected components that must work together, such as a memory chip and a CPU on a motherboard, a quantum computer will need to communicate quantum information between multiple processors.

Current architectures used to interconnect superconducting quantum processors are “point-to-point” in connectivity, meaning they require a series of transfers between network nodes, with compounding error rates.

A study led by the University of Portsmouth has achieved unprecedented precision in detecting tiny shifts in light displacements at the nanoscale. This is relevant in the characterization of birefringent materials and in high-precision measurements of rotations.

The quantum sensing breakthrough is published in the journal Physical Review A, and has the potential to revolutionize many aspects of daily life, industry, and science.

Imagine two photons, massless particles of light, that are intertwined in a unique way, meaning their propagation is connected even when they are separated. When these photons pass through a device that splits the particles of light into two paths—known as a beam-splitter—they interfere with each other in special patterns. By analyzing these patterns, researchers have developed a highly precise method to detect even the tiniest initial spatial shifts between them.

The fate of the universe hinges on the balance between matter and dark energy: the fundamental ingredient that drives its accelerating expansion. New results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) collaboration use the largest 3D map of our universe ever made to track dark energy’s influence over the past 11 billion years. Researchers see hints that dark energy, widely thought to be a “cosmological constant,” might be evolving over time in unexpected ways.

DESI is an international experiment with more than 900 researchers from more than 70 institutions around the world and is managed by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab). The collaboration shared their findings today in multiple papers that will be posted on the online repository arXiv and in a presentation at the American Physical Society’s Global Physics Summit in Anaheim, California.

“What we are seeing is deeply intriguing,” said Alexie Leauthaud-Harnett, co-spokesperson for DESI and a professor at UC Santa Cruz. “It is exciting to think that we may be on the cusp of a major discovery about dark energy and the fundamental nature of our universe.”

Scientists from the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science (CEMS) and collaborators have discovered a new way to control superconductivity—an essential phenomenon for developing more energy-efficient technologies and quantum computing—by simply twisting atomically thin layers within a layered device.

By adjusting the twist angle, they were able to finely tune the “superconducting gap,” which plays a key role in the behavior of these materials. The research is published in Nature Physics.

The superconducting gap is the energy threshold required to break apart Cooper pairs—bound electron pairs that enable superconductivity at low temperatures. Having a larger gap allows superconductivity to persist at higher, more accessible temperatures, and tuning the gap is also important for optimizing Cooper pair behavior at the nanoscale, contributing to the high functionality of quantum devices.