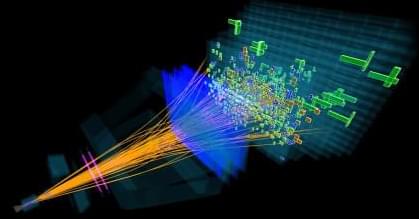

A new analysis of B-meson decays strongly hints that they harbor physics beyond the standard model.

A new method enables researchers to analyze magnetic nanostructures with a high resolution. It was developed by researchers at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics in Halle.

The new method achieves a resolution of around 70 nanometers, whereas normal light microscopes have a resolution of just 500 nanometers. This result is important for the development of new, energy-efficient storage technologies based on spin electronics. The team reports on its research in the current issue of the journal ACS Nano.

Normal optical microscopes are limited by the wavelength of light and details below around 500 nanometers cannot be resolved. The new method overcomes this limit by utilizing the anomalous Nernst effect (ANE) and a metallic nano-scale tip. ANE generates an electrical voltage in a magnetic metal that is perpendicular to the magnetization and a temperature gradient.

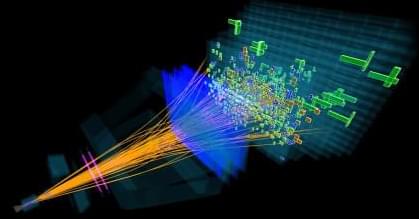

For decades, scientists have used the Milky Way as a model for understanding how galaxies form. But three new studies raise questions about whether the Milky Way is truly representative of other galaxies in the universe.

“The Milky Way has been an incredible physics laboratory, including for the physics of galaxy formation and the physics of dark matter,” said Risa Wechsler, the Humanities and Sciences Professor and professor of physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “But the Milky Way is only one system and may not be typical of how other galaxies formed. That’s why it’s critical to find similar galaxies and compare them.”

To achieve that goal, Wechsler cofounded the Satellites Around Galactic Analogs (SAGA) Survey dedicated to comparing galaxies similar in mass to the Milky Way.

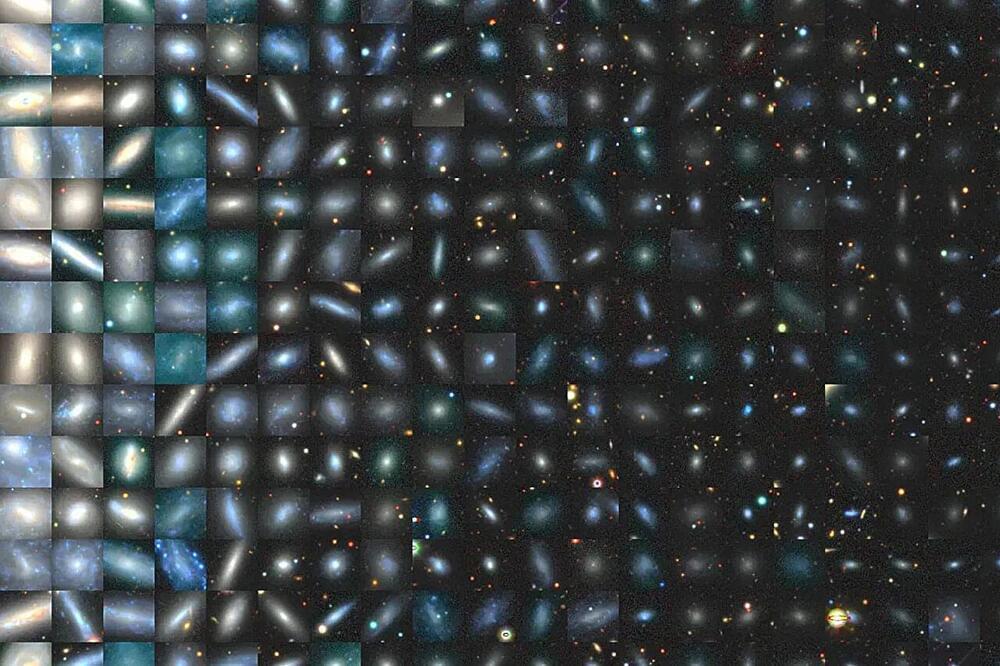

New research into dark matter suggests it might have originated from a “Dark Big Bang,” distinct from the traditional Big Bang.

This theory, which posits a separate cosmic event as the source of dark matter, could change how we understand the universe’s early moments. Upcoming gravitational wave detection experiments could provide critical evidence to support this theory.

Alternative theory of dark matter genesis.

Gravity has shaped our cosmos. Its attractive influence turned tiny differences in the amount of matter present in the early universe into the sprawling strands of galaxies we see today. A new study using data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) has traced how this cosmic structure grew over the past 11 billion years, providing the most precise test to date of gravity at very large scales.

DESI is an international collaboration of more than 900 researchers from over 70 institutions around the world and is managed by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).

In their new study, DESI researchers found that gravity behaves as predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The result validates the leading model of the universe and limits possible theories of modified gravity, which have been proposed as alternative ways to explain unexpected observations—including the accelerating expansion of our universe that is typically attributed to dark energy.

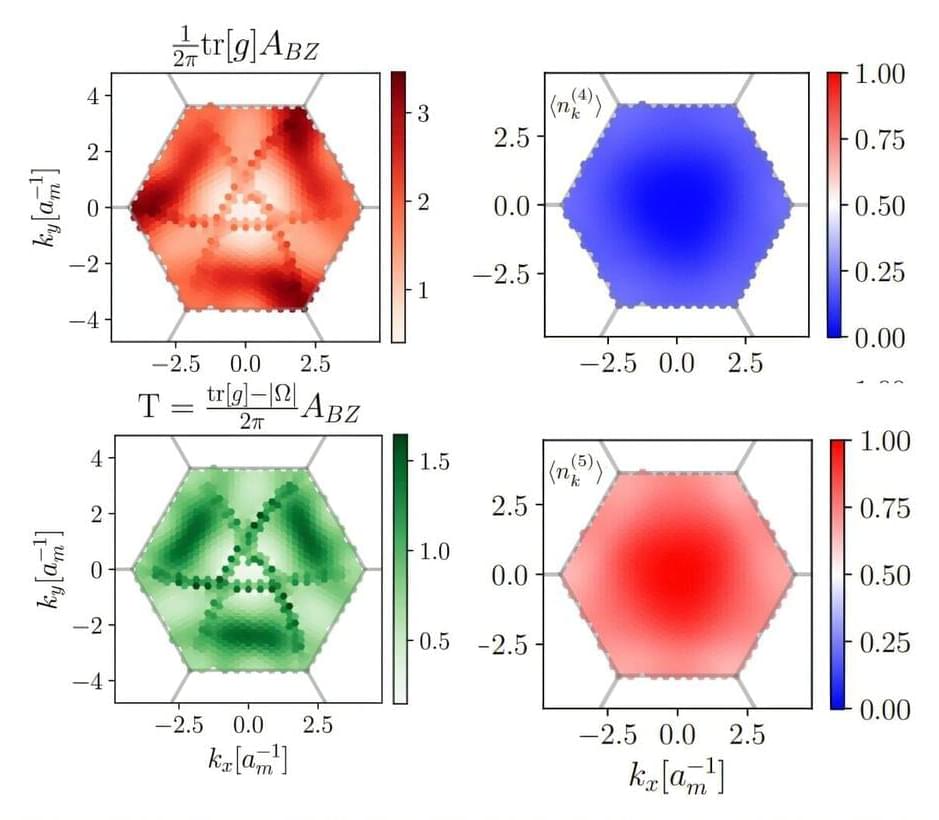

MIT physicists have taken a key step toward solving the puzzle of what leads electrons to split into fractions of themselves. Their solution sheds light on the conditions that give rise to exotic electronic states in graphene and other two-dimensional systems.

The new work is an effort to make sense of a discovery that was reported earlier this year by a different group of physicists at MIT, led by Assistant Professor Long Ju. Ju’s team found that electrons appear to exhibit “fractional charge” in pentalayer graphene—a configuration of five graphene layers that are stacked atop a similarly structured sheet of boron nitride.

Ju discovered that when he sent an electric current through the pentalayer structure, the electrons seemed to pass through as fractions of their total charge, even in the absence of a magnetic field.

Astronomers at the University of Toronto (U of T) have discovered the first pairs of white dwarf and main sequence stars—” dead” remnants and “living” stars—in young star clusters. Described in a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal, this breakthrough offers new insights into an extreme phase of stellar evolution, and one of the biggest mysteries in astrophysics.

Scientists can now begin to bridge the gap between the earliest and final stages of binary star systems—two stars that orbit a shared center of gravity—to further our understanding of how stars form, how galaxies evolve, and how most elements on the periodic table were created. This discovery could also help explain cosmic events like supernova explosions and gravitational waves, since binaries containing one or more of these compact dead stars are thought to be the origin of such phenomena.

Most stars exist in binary systems. In fact, nearly half of all stars similar to our sun have at least one companion star. These paired stars usually differ in size, with one star often being more massive than the other. Though one might be tempted to assume that these stars evolve at the same rate, more massive stars tend to live shorter lives and go through the stages of stellar evolution much faster than their lower mass companions.

A team of astrophysicists, led by our Institute for Computational Cosmology, have developed a new model that could estimate how likely it is for intelligent life to emerge in our Universe and beyond.

In the 1960s, American astronomer Dr Frank Drake came up with an equation to calculate the number of detectable extraterrestrial civilisations in our Milky Way galaxy.

More than 60 years on, researchers at Durham, the University of Edinburgh and the Université de Genève, have produced a new model based on the conditions created by the acceleration of the Universe’s expansion and the amount of stars formed instead.

Team develops simulation algorithms for safer, greener, and more aerodynamic aircraft.

Ice buildup on aircraft wings and fuselage occurs when atmospheric conditions conducive to ice formation are encountered during flight, presenting a critical area of focus for their research endeavors.

Ice accumulation on an aircraft during flight poses a significant risk, potentially impairing its performance and, in severe cases, leading to catastrophic consequences.

Fernández’s laboratory is dedicated to the development of algorithms and software tools aimed at comprehensively understanding these processes and leveraging this knowledge to enhance future aircraft designs, thereby mitigating potential negative outcomes.

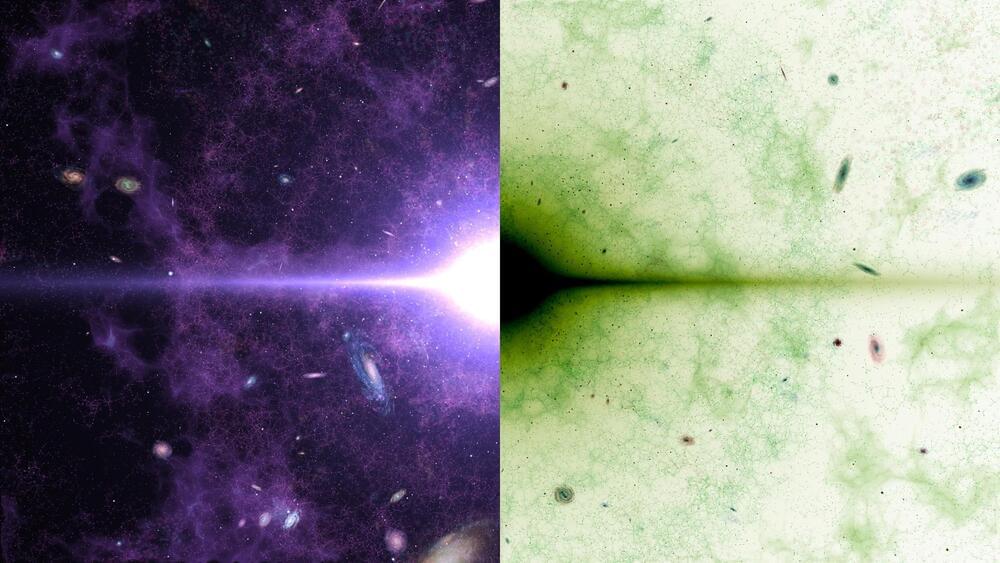

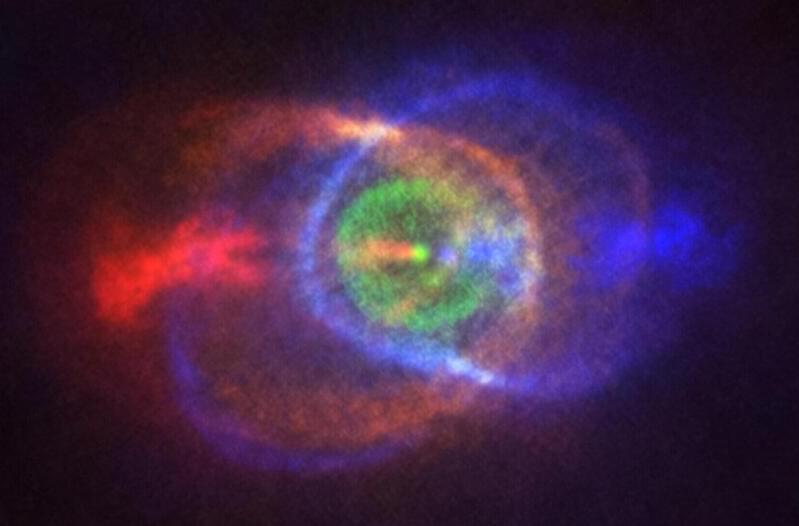

Astounding simulation shows magnetic fields create fluffy, not flat, accretion disks around supermassive black holes, altering our understanding of black hole dynamics.

A team of astrophysicists from Caltech has achieved a groundbreaking milestone by simulating the journey of primordial gas from the early universe to its incorporation into a disk of material feeding a supermassive black hole. This innovative simulation challenges theories about these disks that have persisted since the 1970s and opens new doors for understanding the growth and evolution of black holes and galaxies.

“Our new simulation marks the culmination of several years of work from two large collaborations started here at Caltech,” says Phil Hopkins, the Ira S. Bowen Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics.