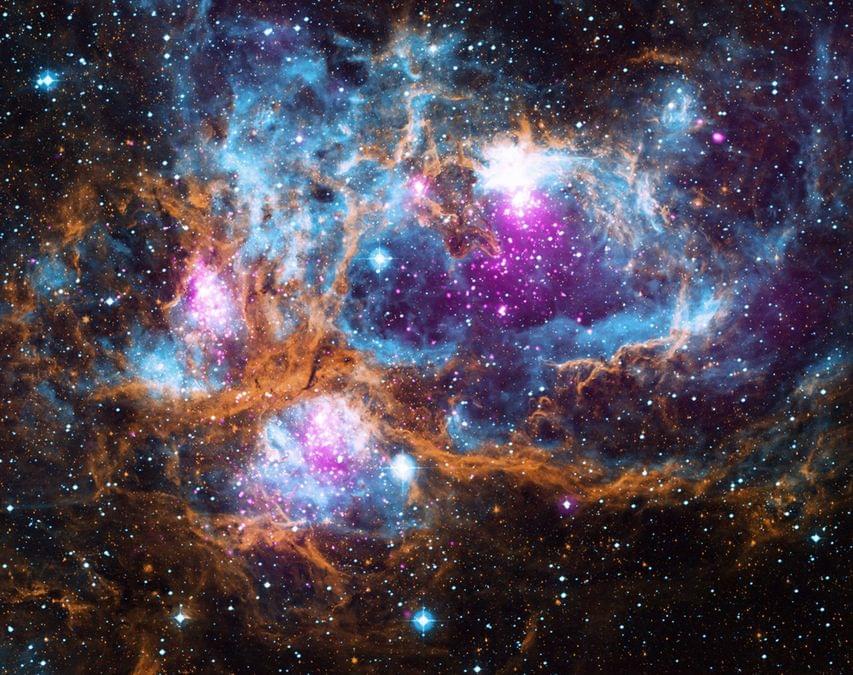

Superconducting materials are similar to the carpool lane in a congested interstate. Like commuters who ride together, electrons that pair up can bypass the regular traffic, moving through the material with zero friction.

But just as with carpools, how easily electron pairs can flow depends on a number of conditions, including the density of pairs that are moving through the material. This “superfluid stiffness,” or the ease with which a current of electron pairs can flow, is a key measure of a material’s superconductivity.

Physicists at MIT and Harvard University have now directly measured superfluid stiffness for the first time in “magic-angle” graphene—materials that are made from two or more atomically thin sheets of graphene twisted with respect to each other at just the right angle to enable a host of exceptional properties, including unconventional superconductivity.