An email reveals what I have been saying for long…Hossenfelder’s video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shFUDPqVmTgMy books: www.amazon.com/Alexander-Unzi…

Category: physics – Page 74

Mind uploading and continuity

If you think I live in the twilight zone your right.

As a computational functionalist, I think the mind is a system that exists in this universe and operates according to the laws of physics. Which means that, in principle, there shouldn’t be any reason why the information and dispositions that make up a mind can’t be recorded and copied into another substrate someday, such as a digital environment.

To be clear, I think this is unlikely to happen anytime soon. I’m not in the technological singularity camp that sees us all getting uploaded into the cloud in a decade or two, the infamous “rapture of the nerds”. We need to understand the brain far better than we currently do, and that seems several decades to centuries away. Of course, if it is possible to do it anytime soon, it won’t be accomplished by anyone who’s already decided it’s impossible, so I enthusiastically cheer efforts in this area, as long as it’s real science.

There have always been a number of objections to the idea of uploading. Many people just reflexively assume it’s categorically impossible. Certainly we don’t have the technology today, but short of assuming the mind is at least partially non-physical, it’s hard to see what the ultimate obstacle might be. Even with that assumption, who can say that a copied mind wouldn’t have those non-physical properties? David Chalmers, a property dualist, sees those non-physical properties as corresponding with the right functionality, so for him AI consciousness and mind copying remain a possibility.

Gravitational waves could turn colliding neutron stars into ‘cosmic tuning forks’

“Just like tuning forks of different material will have different pure tones, remnants described by different equations of state will ring down at different frequencies,” Rezzolla said in a statement. “The detection of this signal thus has the potential to reveal what neutron stars are made of.”

Gravitational waves were first suggested by Albert Einstein in this 1915 theory of gravity, known as general relativity.

Why is space three-dimensional? with Stephen Wolfram

I love his hypergraph theory.

Hypergraphs can have any number of dimensions. They can be 2-dimensional, 3-dimensional, 4.81-dimensional or, in the limit, ∞-dimensional.

So how does the three-dimensional space we observe emerge from the hypergraph-based Wolfram model?

Why is space three-dimensional?

Stephen Wolfram’s surprising answer to this questions goes deep into space, time, computation and, crucially, our nature as observers.

New optical tech boosts gravitational-wave detection capabilities

In a paper published earlier this month in Physical Review Letters, a team of physicists led by Jonathan Richardson of the University of California, Riverside, showcases how new optical technology can extend the detection range of gravitational-wave observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, and pave the way for future observatories.

Since 2015, observatories like LIGO have opened a new window on the universe. Plans for future upgrades to the 4-kilometer LIGO detectors and the construction of a next-generation 40-kilometer observatory, Cosmic Explorer, aim to push the gravitational-wave detection horizon to the earliest times in the history of the universe, before the first stars formed. However, realizing these plans hinges on achieving laser power levels exceeding 1 megawatt, far beyond LIGO’s capabilities today.

The research paper reports a breakthrough that will enable gravitational-wave detectors to reach extreme laser powers. It presents a new low-noise, high-resolution adaptive optics approach that can correct the limiting distortions of LIGO’s main 40-kilogram mirrors which arise with increasing laser power due to heating.

From collisions to stellar cannibalism—the surprising diversity of exploding white dwarfs

Astrophysicists have unearthed a surprising diversity in the ways in which white dwarf stars explode in deep space after assessing almost 4,000 such events captured in detail by a next-gen astronomical sky survey. Their findings may help us more accurately measure distances in the universe and further our knowledge of “dark energy.”

The dramatic explosions of white dwarf stars at the ends of their lives have for decades played a pivotal role in the study of dark energy—the mysterious force responsible for the accelerating expansion of the universe. They also provide the origin of many elements in our periodic table, such as titanium, iron and nickel, which are formed in the extremely dense and hot conditions present during their explosions.

A major milestone has been achieved in our understanding of these explosive transients with the release of a major dataset, and associated 21 publications in an Astronomy & Astrophysics special issue.

Greetings from the fourth dimension: Scientists glimpse 4D crystal structure using surface wave patterns

In April 1982, Prof. Dan Shechtman of the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology made the discovery that would later earn him the 2011 Nobel Prize in Chemistry: the quasiperiodic crystal. According to diffraction measurements made with an electron microscope, the new material appeared “disorganized” at smaller scales, yet with a distinct order and symmetry apparent at a larger scale.

This form of matter was considered impossible, and it took many years to convince the scientific community of the discovery’s validity. The first physicists to theoretically explain this discovery were Prof. Dov Levine, then a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania and now a faculty member in the Technion Physics department, and his advisor, Prof. Paul Steinhardt.

The key insight that enabled their explanation was that quasicrystals were, in fact, periodic—but in a higher dimension than the one in which they exist physically. Using this realization, the physicists were able to describe and predict mechanical and thermodynamic properties of quasicrystals.

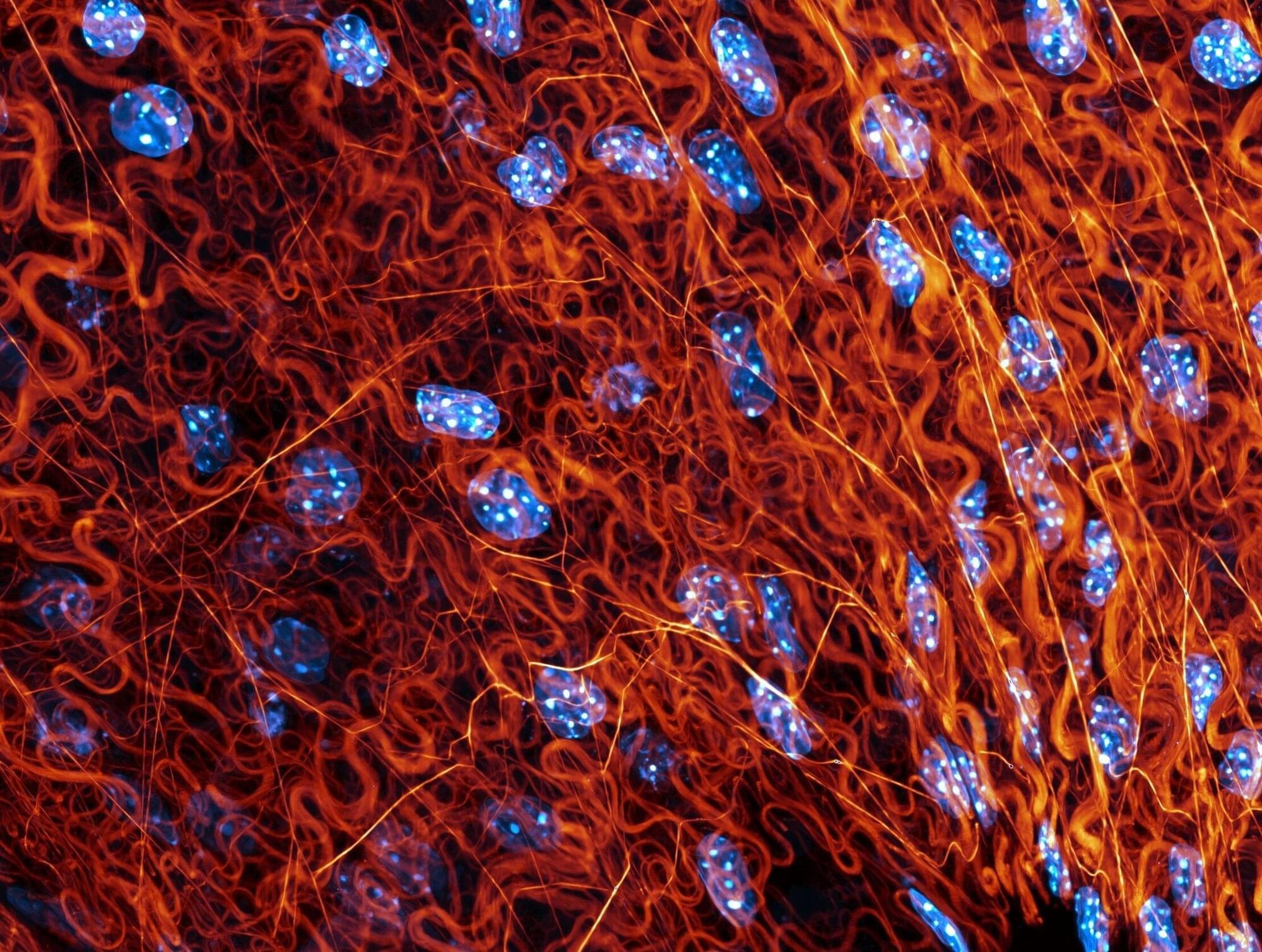

Looking between cells: Light microscopy probe provides unprecedented view of extracellular matrix

Before arriving at Janelia three years ago, Postdoctoral Scientist Antonio Fiore was designing and building optical instruments like microscopes and spectrometers. Fiore, a physicist by training, came to the Pedram Lab to try something new.

“I focused on the physics rather than investing in the biological applications of the optics I was developing,” Fiore says. “I came to the Pedram Lab in search of a different kind of impact, joining a team that explores areas of biology that need new tools, while keeping a connection to light microscopy.”

So far, Fiore’s new direction is paying off.

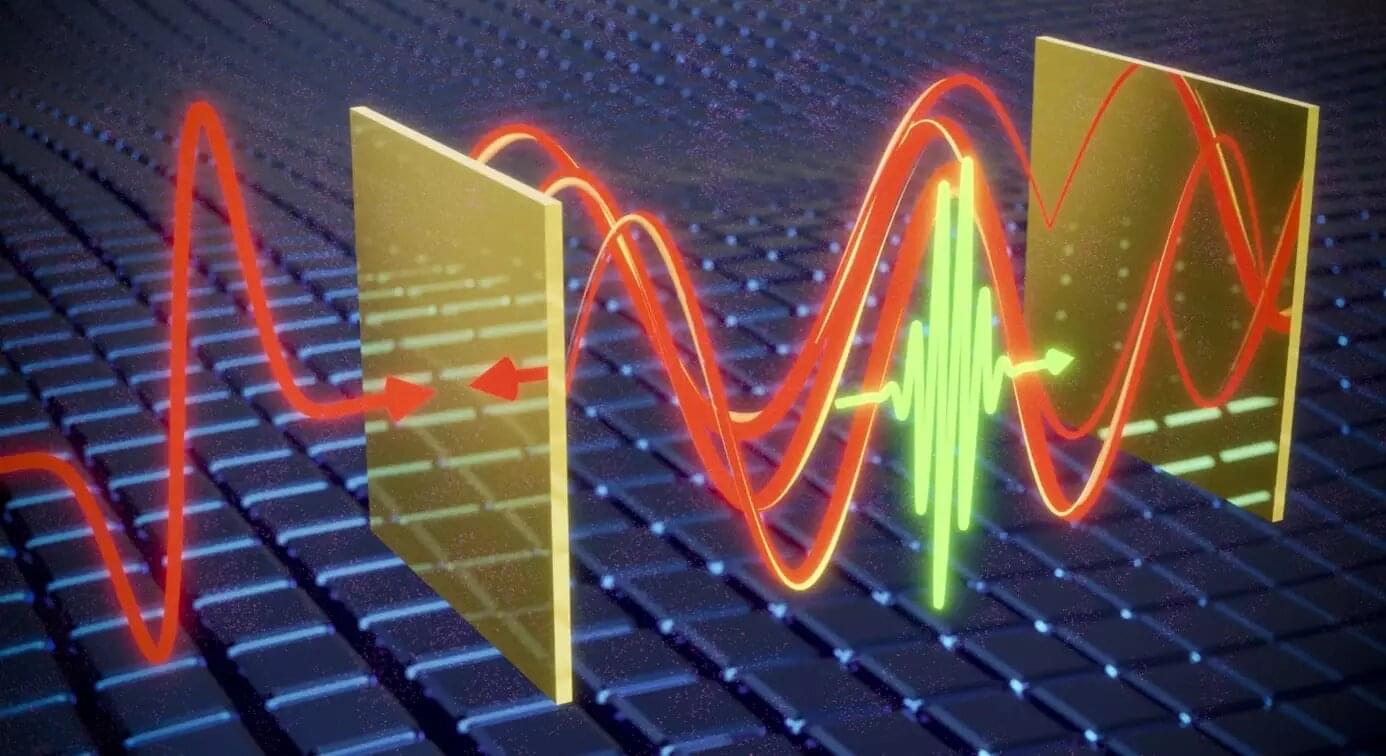

Measuring invisible light waves via electro-optic cavities

Researchers have developed a novel experimental platform to measure the electric fields of light trapped between two mirrors with a sub-cycle precision.

These electro-optic Fabry-Pérot resonators will allow for precise control and observation of light-matter interactions, particularly in the terahertz (THz) spectral range. The study is published in the journal Light: Science & Applications.

The researchers are from the Department of Physical Chemistry at the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society and the Institute of Radiation Physics at Helmholtz Center Dresden-Rossendorf.