Scientists believe that time is continuous, not discrete—roughly speaking, they believe that it does not progress in “chunks,” but rather “flows,” smoothly and continuously. So they often model the dynamics of physical systems as continuous-time “Markov processes,” named after mathematician Andrey Markov. Indeed, scientists have used these processes to investigate a range of real-world processes from folding proteins, to evolving ecosystems, to shifting financial markets, with astonishing success.

However, invariably a scientist can only observe the state of a system at discrete times, separated by some gap, rather than continually. For example, a stock market analyst might repeatedly observe how the state of the market at the beginning of one day is related to the state of the market at the beginning of the next day, building up a conditional probability distribution of what the state of the second day is given the state at the first day.

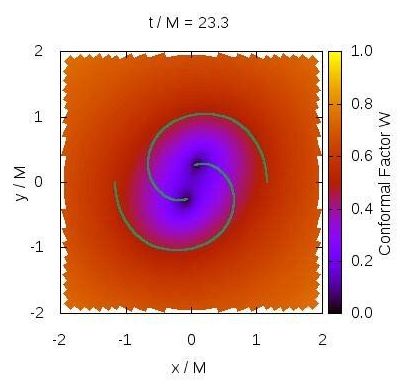

In a pair of papers, one appearing in this week’s Nature Communications and one appearing recently in the New Journal of Physics, physicists at the Santa Fe Institute and MIT have shown that in order for such two–time dynamics over a set of “visible states” to arise from a continuous-time Markov process, that Markov process must actually unfold over a larger space, one that includes hidden states in addition to the visible ones. They further prove that the evolution between such a pair of times must proceed in a finite number of “hidden timesteps”, subdividing the interval between those two times. (Strictly speaking, this proof holds whenever that evolution from the earlier time to the later time is noise-free—see paper for technical details.)

Read more