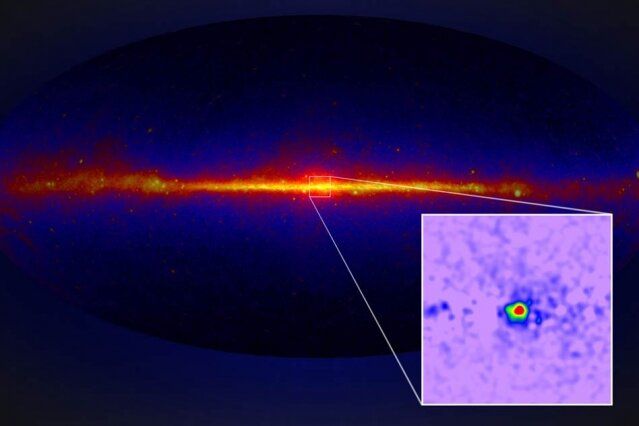

MIT physicists are reigniting the possibility, which they previously had snuffed out, that a bright burst of gamma rays at the center of our galaxy may be the result of dark matter after all.

For years, physicists have known of a mysterious surplus of energy at the Milky Way’s center, in the form of gamma rays—the most energetic waves in the electromagnetic spectrum. These rays are typically produced by the hottest, most extreme objects in the universe, such as supernovae and pulsars.

Gamma rays are found across the disk of the Milky Way, and for the most part physicists understand their sources. But there is a glow of gamma rays at the Milky Way’s center, known as the galactic center excess, or GCE, with properties that are difficult for physicists to explain given what they know about the distribution of stars and gas in the galaxy.