If you are interested in mind uploading, then I have a research paper for you to consider. One of the serious issues with mind uploading is the computer substrate. Simulating the brain will require a new and incredible computing capability. New techniques and new hardware are going to be required to make it practical. Of course, there is currently zero demand for mind uploading hardware, so the market is not going to provide this capability. However, there is incredible market demand for cutting edge hardware for machine learning and artificial intelligence. And it turns out that one potential technique for artificial intelligence simulates the way that the brain works: neuromorphic computing. And there is a relatively new type of electronic component that seems to mimic some of the functions of a brain’s neuron: the memristor. Memristors are relatively new, having only been fabricated for the first time by HP in 2008. So I am trying to keep up with the latest developments in memristive technology.

Here are some excerpts from the paper:

“…Artificial Neural Network (ANN) algorithms offer fast computations by mimicking the neuronal network of brains. A weight matrix is used in neural networks (NNs) for parallel processing that makes computing faster…The memristor has attracted much attention because of its potential to have linear multilevel conductance states for vector-matrix multiplication (output = weight × input), corresponding to parallel processing…”

Here is a web link to the research paper:

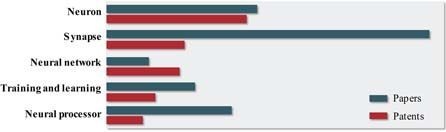

Neuromorphic computation is one of the axes of parallel distributed processing, and memristor-based synaptic weight is considered as a key component of this type of computation. However, the material properties of memristors, including material related physics, are not yet matured. In parallel with memristors, CMOS based Graphics Processing Unit, Field Programmable Gate Array, and Application Specific Integrated Circuit are also being developed as dedicated artificial intelligence (AI) chips for fast computation. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the competitiveness of the memristor-based neuromorphic device in order to position the memristor in the appropriate position of the future AI ecosystem. In this article, the status of memristor-based neuromorphic computation was analyzed on the basis of papers and patents to identify the competitiveness of the memristor properties by reviewing industrial trends and academic pursuits. In addition, material issues and challenges are discussed for implementing the memristor-based neural processor.