However, if you’re rich and you don’t like the idea of a limit on computing, you can turn to futurism, longtermism, or “AI optimism,” depending on your favorite flavor. People in these camps believe in developing AI as fast as possible so we can (they claim) keep guardrails in place that will prevent AI from going rogue or becoming evil. (Today, people can’t seem to—or don’t want to—control whether or not their chatbots become racist, are “sensual” with children, or induce psychosis in the general population, but sure.)

The goal of these AI boosters is known as artificial general intelligence, or AGI. They theorize, or even hope for, an AI so powerful that it thinks like… well… a human mind whose ability is enhanced by a billion computers. If someone ever does develop an AGI that surpasses human intelligence, that moment is known as the AI singularity. (There are other, unrelated singularities in physics.) AI optimists want to accelerate the singularity and usher in this “godlike” AGI.

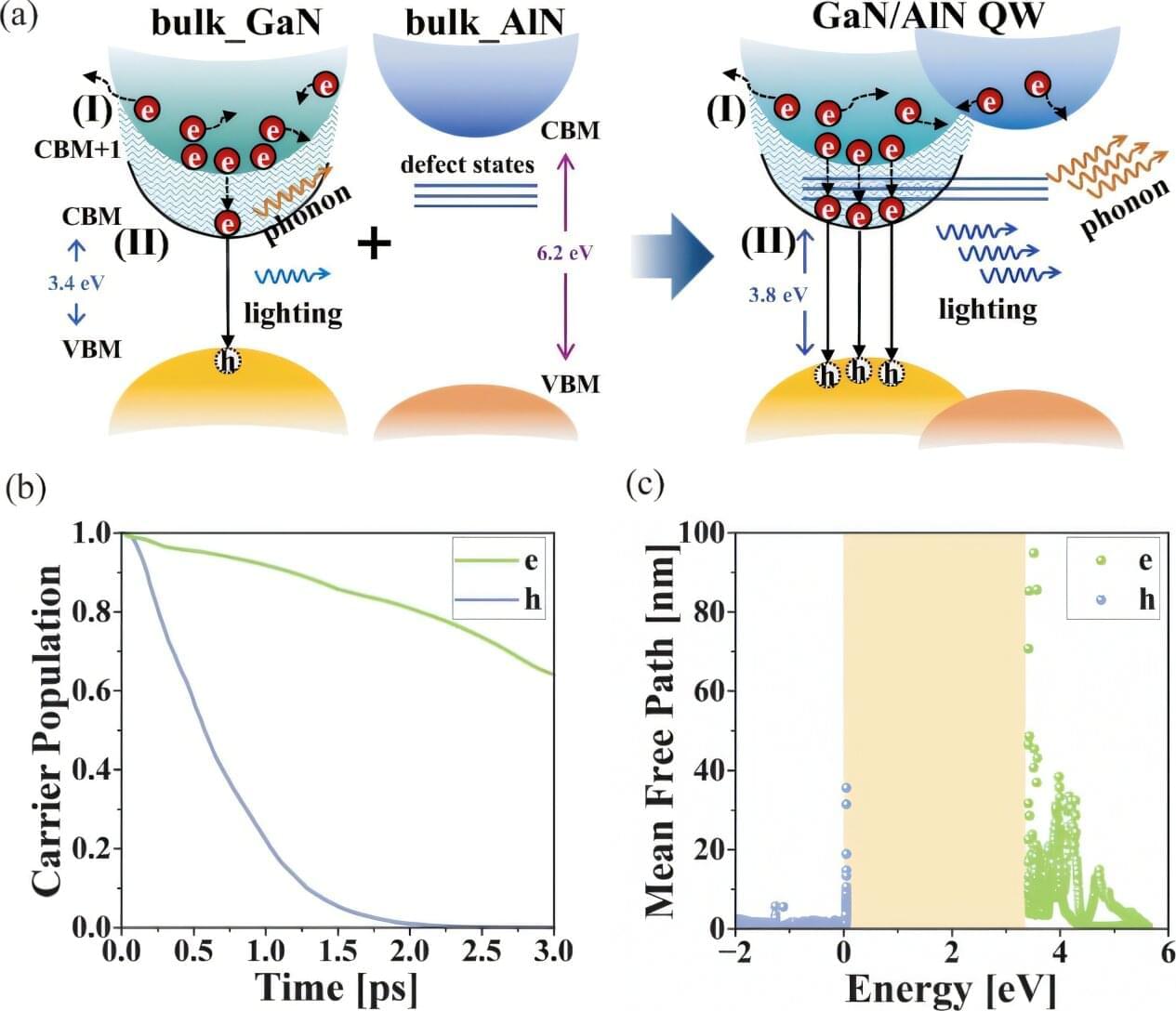

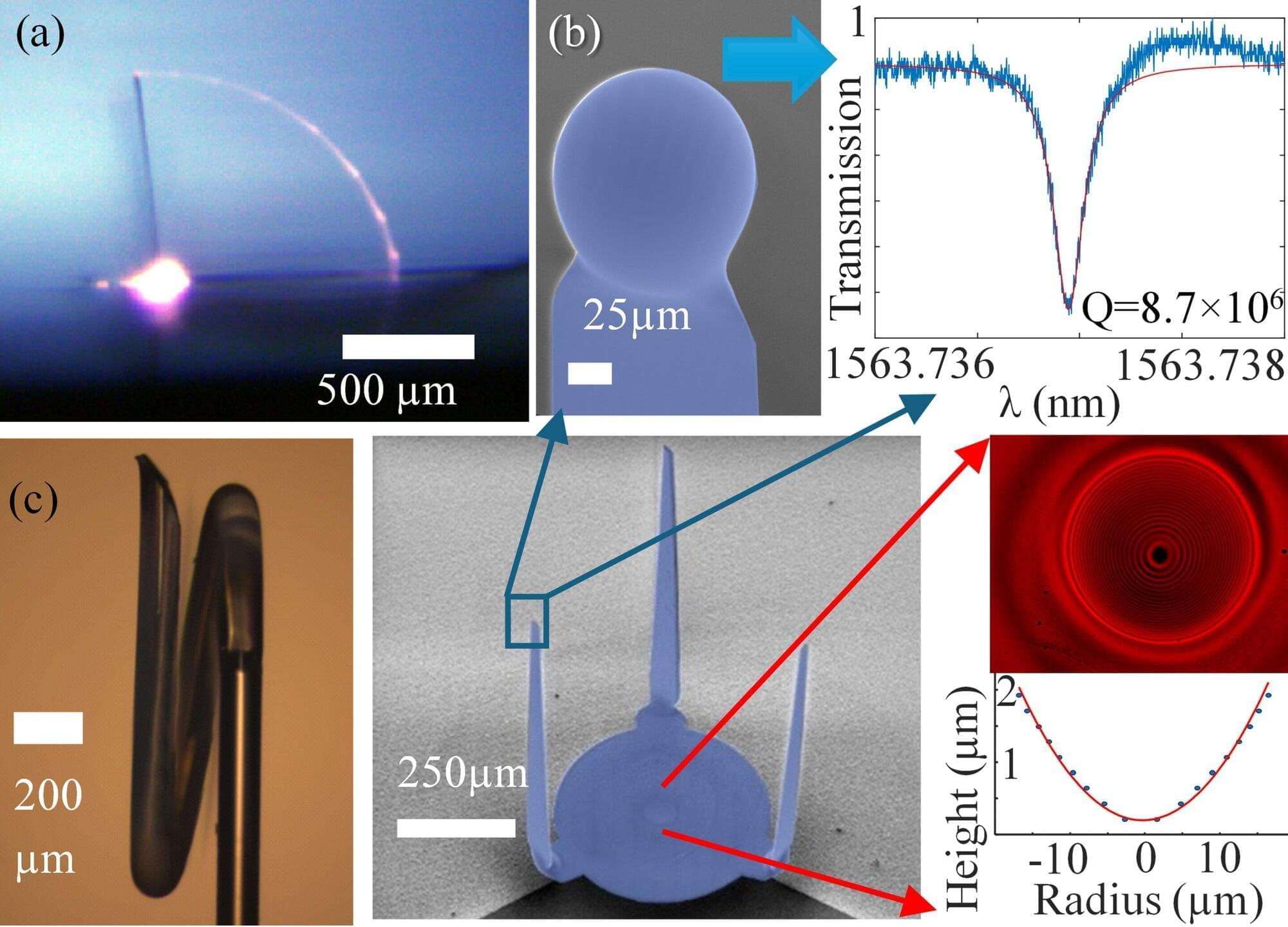

One of the key facts of computer logic is that, if you can slow the processes down enough and look at it in enough detail, you can track and predict every single thing that a program will do. Algorithms (and not the opaque AI kind) guide everything within a computer. Over the decades, experts have written the exact ways information can be sent, one bit—one minuscule electrical zap—at a time through a central processing unit (CPU).