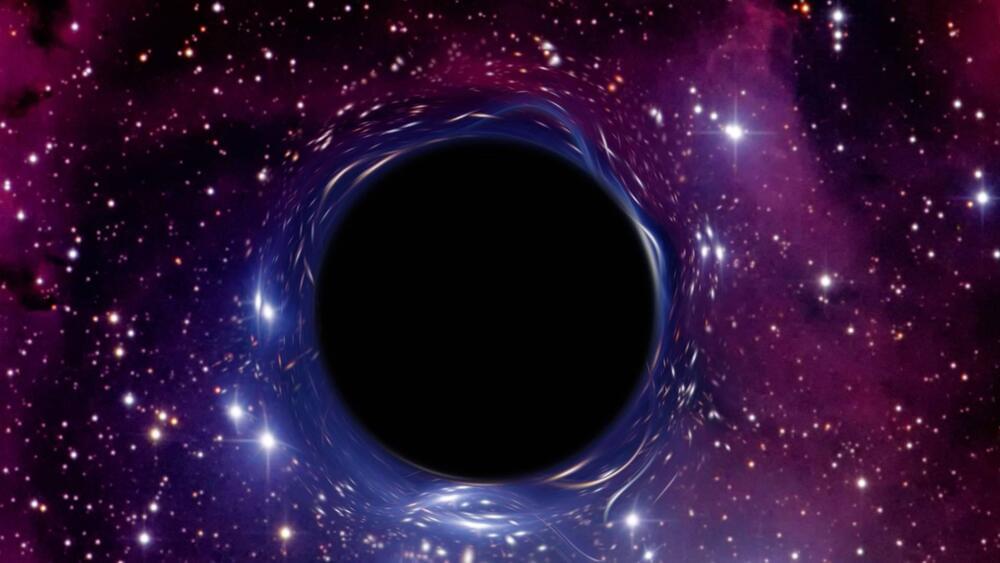

The first GWs were detected in 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO), when two black holes about 1.3 billion light-years away slammed into each other. LIGO consists of two interferometers — one in Louisiana, one in Washington state — which are L-shaped vacuum tunnels about 2.5 miles long on each side. A laser is shot from the crux of the L to mirrors at the end of each side, and if one of those laser beams arrives slightly late, the tardy beam is recorded by the detector. The detectors are sensitive enough to pick up nearby noises on Earth as well, such as passing trucks and falling trees. These events can mask or mimic gravitational-wave signals, so having two detectors far apart helps scientists distinguish real GW vibrations from false alarms.

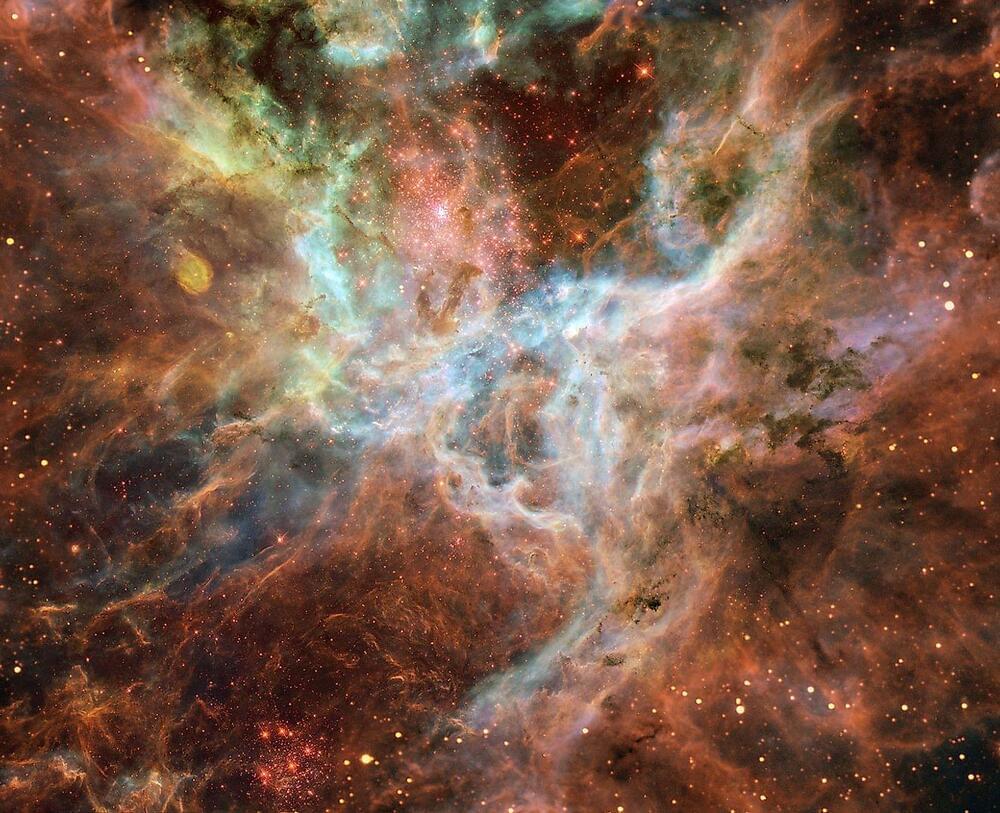

The actual detector that spotted the first gravitational wave is now in the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm, Sweden, as the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics was awarded for this discovery. But LIGO didn’t stop there: A few months later, in collaboration with the newly completed Virgo interferometer in Italy, LIGO detected another gravitational wave event — this time produced by colliding neutron stars. The discovery also corresponded with a short gamma-ray burst and subsequent discovery of the merger site with optical telescopes. Within days of that momentous discovery, however, LIGO went offline for scheduled upgrades.