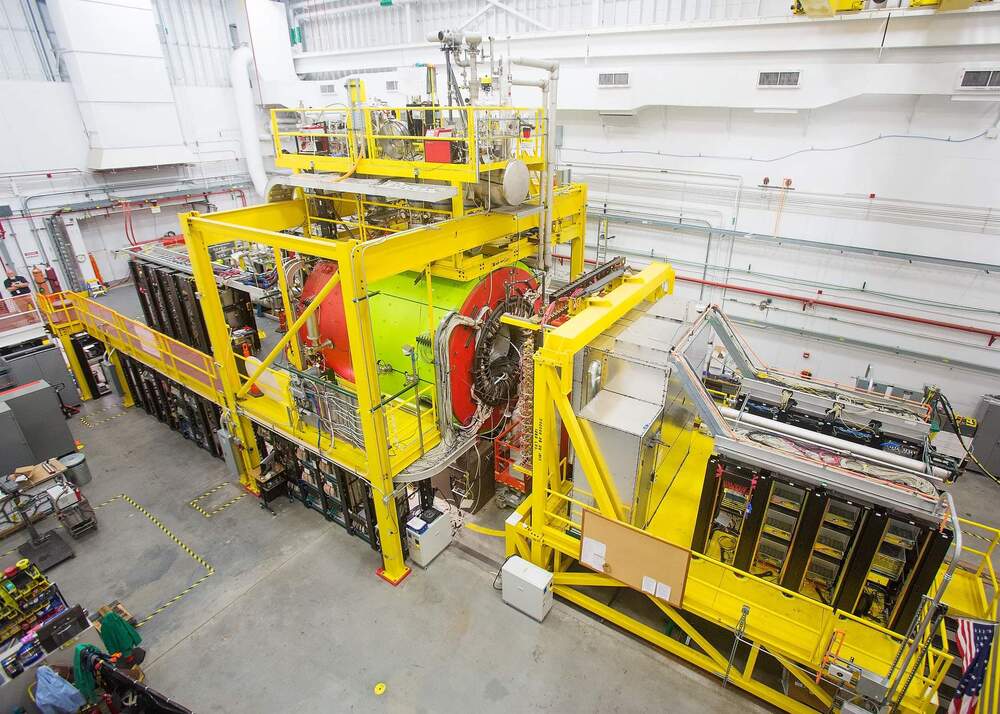

Nuclear physicists have confirmed that the current description of proton structure isn’t all smooth sailing. A new precision measurement of the proton’s electric polarizability performed at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility has revealed a bump in the data in probes of the proton’s structure.

Though widely thought to be a fluke when seen in earlier measurements, this new, more precise measurement has confirmed the presence of the anomaly and raises questions about its origin. The research has just been published in the journal Nature.

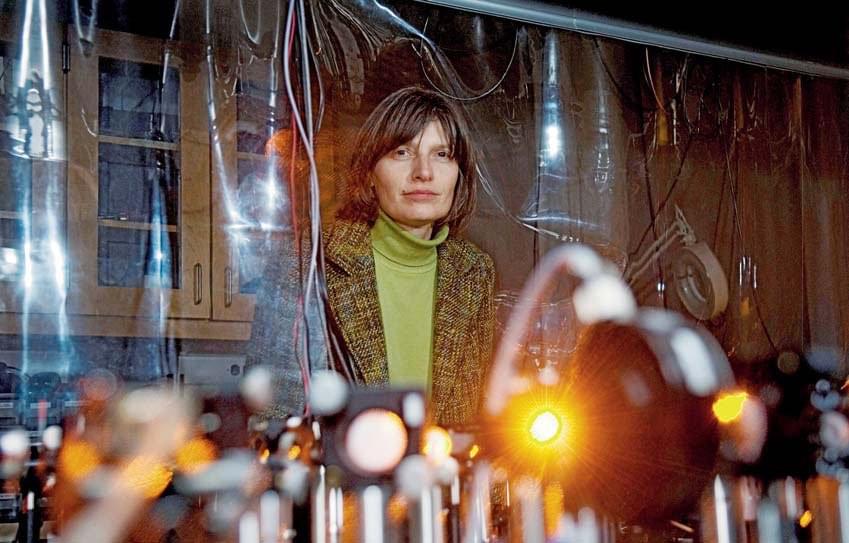

According to Ruonan Li, first author on the new paper and a graduate student at Temple University, measurements of the proton’s electric polarizability reveal how susceptible the proton is to deformation, or stretching, in an electric field. Like size or charge, the electric polarizability is a fundamental property of proton structure.