A presentation on the conception of the present moment in physics and cognitive neuroscience (presented at the 3rd European Summer School in Process Thought in Düsseldorf, Germany, 25–29 September 2014).

Category: physics – Page 170

New Night Vision Tech Lets AI See in Pitch Darkness Like It’s Broad Daylight

It’s no surprise that machines have the same problem. Although they’re armed with a myriad of sensors, self-driving cars are still trying to live up to their name. They perform well under perfect weather conditions and roads with clear traffic lanes. But ask the cars to drive in heavy rain or fog, smoke from wildfires, or on roads without streetlights, and they struggle.

This month, a team from Purdue University tackled the low visibility problem head-on. Combining thermal imaging, physics, and machine learning, their technology allowed a visual AI system to see in the dark as if it were daylight.

At the core of the system are an infrared camera and AI, trained on a custom database of images to extract detailed information from given surroundings—essentially, teaching itself to map the world using heat signals. Unlike previous systems, the technology, called heat-assisted detection and ranging (HADAR), overcame a notorious stumbling block: the “ghosting effect,” which usually causes smeared, ghost-like images hardly useful for navigation.

Why Isaac Newton’s laws still give physicists a lot to think about

The apparent equivalence of gravitational mass to inertial mass is a remarkable and beautiful feature of the cosmos, with a deep implication, says Chanda Prescod-Weinstein

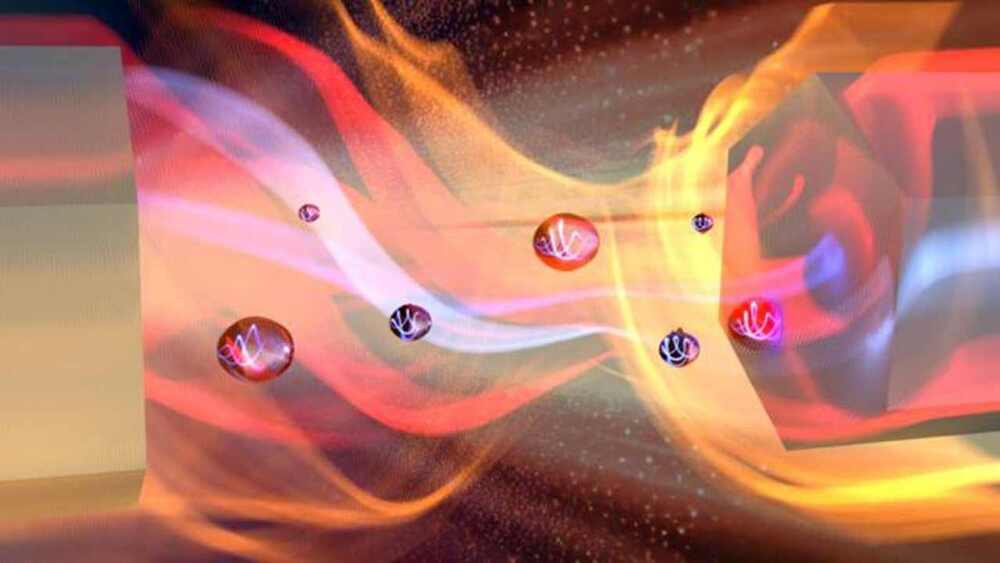

Collision Course: Electromagnetic Waves Interact in Groundbreaking Experiment

Researchers show it’s possible to make photons that cross paths interact, paving the way for technology breakthroughs.

A research team at the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center (CUNY ASRC) has demonstrated that it is possible to manipulate photons so that they can collide, interacting in new ways as they cross paths. Detailed in the journal Nature Physics.

As the name implies, Nature Physics is a peer-reviewed, scientific journal covering physics and is published by Nature Research. It was first published in October 2005 and its monthly coverage includes articles, letters, reviews, research highlights, news and views, commentaries, book reviews, and correspondence.

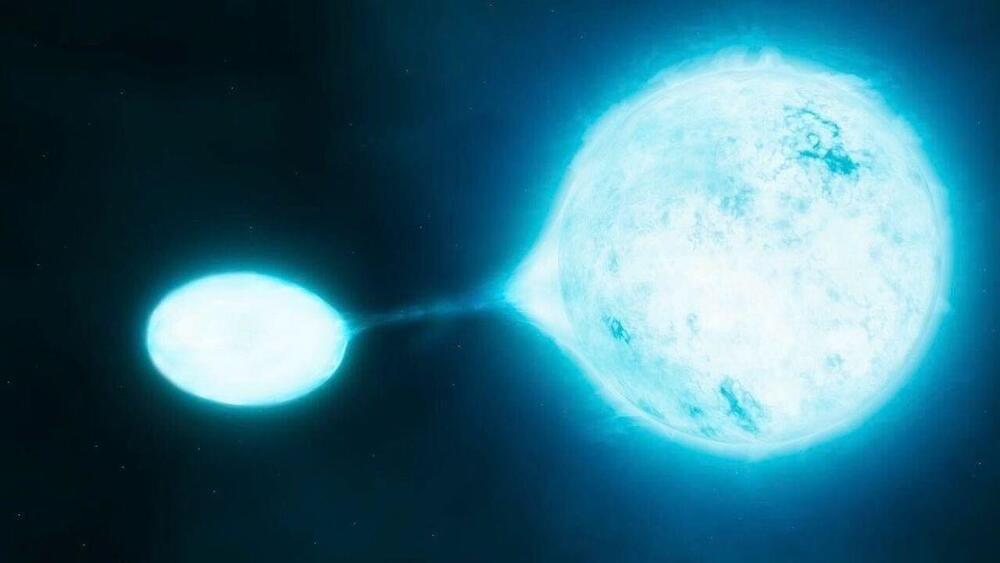

New study challenges Einstein and Newton’s theories of gravity

No, it’s not dark matter.

Gravity is the force that attracts objects toward the Earth and maintains the orbital motion of planets around the Sun. Our scientific understanding of gravity was established by Isaac Newton.

Despite the many successes of Einstein’s theory of gravity, many phenomena, such as gravity inside a black hole and gravitational waves, can’t be explained.

Tod Strohmayer (GSFC), CXC, NASA — Illustration: Dana Berry (CXC)

Our scientific understanding of gravity was established by Isaac Newton in 1687. Newton’s theory of gravity stood the test of time for two centuries until Albert Einstein proposed his ‘General Theory of Relativity,’ filling in the gaps left by Newton’s theory of gravity.

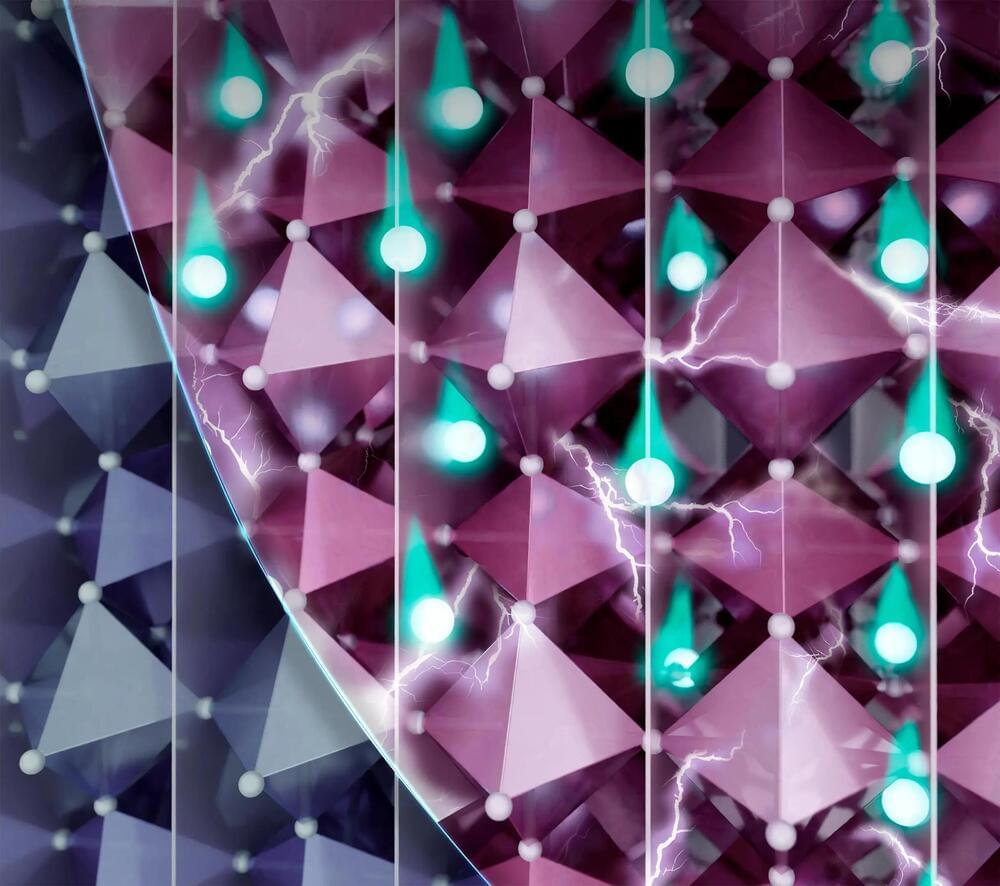

Iontronics Breakthrough: Faster Thin Film Devices for Improved Batteries and Advanced Computing

An international team finds new single-crystalline oxide thin films with fast and dramatic changes in electrical properties via Li-ion intercalation through engineered ionic transport channels.

Researchers have pioneered the creation of T-Nb2O5 thin films that enable faster Li-ion movement. This achievement, promising more efficient batteries and advances in computing and lighting, marks a significant leap forward in iontronics.

An international research team, comprising members from the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics, Halle (Saale), Germany, the University of Cambridge, UK, and the University of Pennsylvania, USA, have reported an important breakthrough in materials science. They achieved the first realization of single-crystalline T-Nb2O5 thin films, exhibiting two-dimensional (2D) vertical ionic transport channels. This results in a swift and significant insulator-metal transition through Li-ion intercalation in the 2D channels.

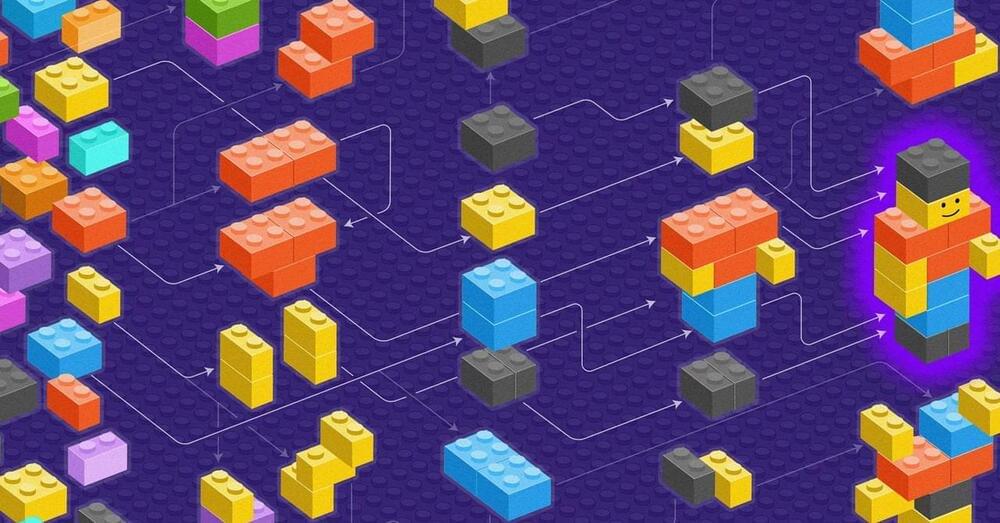

A New Idea for How to Assemble Life

These and other missions on the horizon will face the same obstacle that has plagued scientists since they first attempted to search for signs of Martian biology with the Viking landers in the 1970s: There is no definitive signature of life.

That might be about to change. In 2021, a team led by Lee Cronin of the University of Glasgow in Scotland and Sara Walker of Arizona State University proposed a very general way to identify molecules made by living systems—even those using unfamiliar chemistries. Their method, they said, simply assumes that alien life forms will produce molecules with a chemical complexity similar to that of life on Earth.

Called assembly theory, the idea underpinning the pair’s strategy has even grander aims. As laid out in a recent series of publications, it attempts to explain why apparently unlikely things, such as you and me, even exist at all. And it seeks that explanation not, in the usual manner of physics, in timeless physical laws, but in a process that imbues objects with histories and memories of what came before them. It even seeks to answer a question that has perplexed scientists and philosophers for millennia: What is life, anyway?

Breaking Physics: Muon G-2 Experiment Reinforces Surprise Result, Setting Up “Ultimate Showdown”

Findings at Fermilab show discrepancy between theory and experiment, which may lead to new physics beyond the Standard Model.

Physicists now have a brand-new measurement of a property of the muon called the anomalous magnetic moment that improves the precision of their previous result by a factor of 2.

An international collaboration of scientists working on the Muon g-2 experiment at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory announced the much-anticipated updated measurement on August 10. This new value bolsters the first result they announced in April 2021, and sets up a showdown between theory and experiment over 20 years in the making.

Scientists Achieve the Impossible by transmitting Sound Through Empty Space (Vacuum)

The classic film “Alien” was once promoted with the tagline “In space, no one can hear you scream.” Physicists Zhuoran Geng and Ilari Maasilta from the Nanoscience Center at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, have demonstrated that, on the contrary, in certain situations, sound can be transmitted strongly across a vacuum region.

In a recent article published in Communications Physics they show that in some cases, a sound wave can jump or “tunnel” fully across a vacuum gap between two solids if the materials in question are piezoelectric. In such materials, vibrations (sound waves) produce an electrical response as well, and since an electric field can exist in vacuum, it can transmit the sound waves.

The requirement is that the size of the gap is smaller than the wavelength of the sound wave. This effect works not only in audio range of frequencies (Hz–kHz), but also in ultrasound (MHz) and hypersound (GHz) frequencies, as long as the vacuum gap is made smaller as the frequencies increase.