Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay, the birthplace of modern astrophysics, announced on May 10 the appointment of Dr. Amy Steele as its new Director of Astronomy and Research.

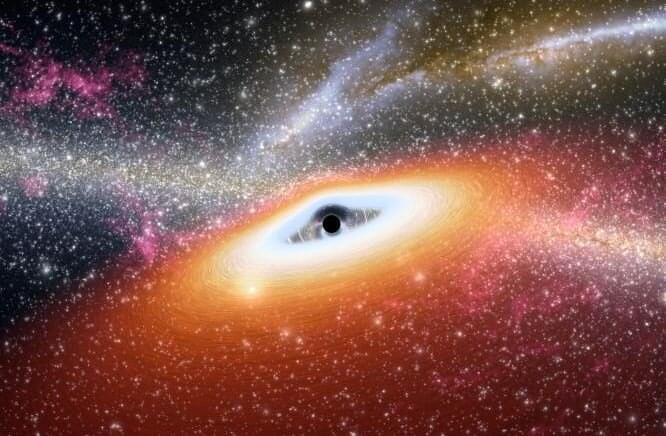

Coming to Yerkes from the Trottier Space Institute in Montréal, Quebec, Canada, Steele studies the building blocks of planets living around stars like our sun that have reached the final phase of their lives. She will begin her role in June, reporting to Yerkes’ Montgomery Foundation Deputy Director and Head of Science and Education Dr. Amanda Bauer.

“The opportunity to lead the direction of astronomy and research at Yerkes is a dream come true for me as an astronomer,” Steele said. “It is an honor to be able to work alongside an adventurous and passionate team who share the same love for this observatory and communion with the night sky. I am truly excited to collaborate with my colleagues and the Yerkes Future Foundation to inspire astronomers young and old, near and far, to follow their curiosity and chase their dreams.”