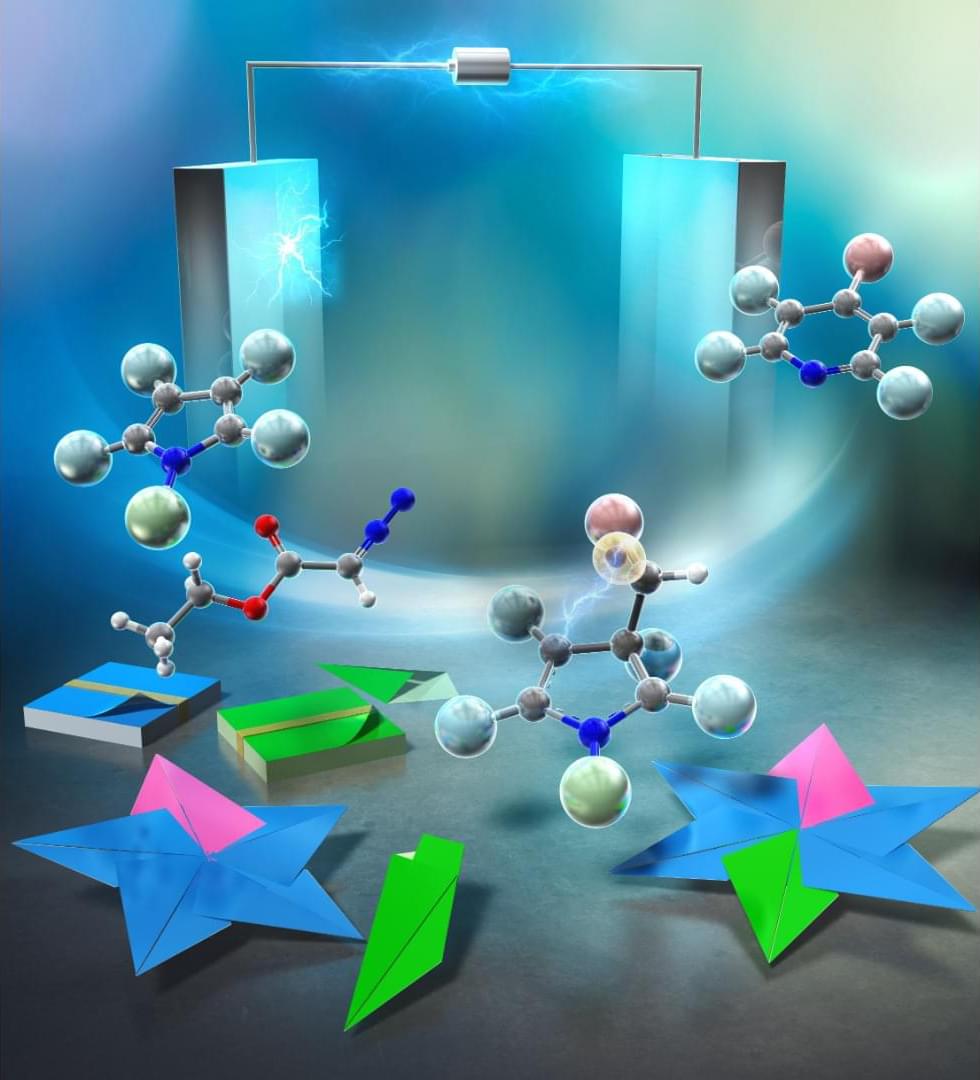

While the technology of nuclear batteries has been available since the 1950s, today’s drive to electrify and decarbonize increases the impetus to find emission-free power sources and reliable energy storage. As a result, innovations are bringing renewed focus to nuclear energy in batteries.

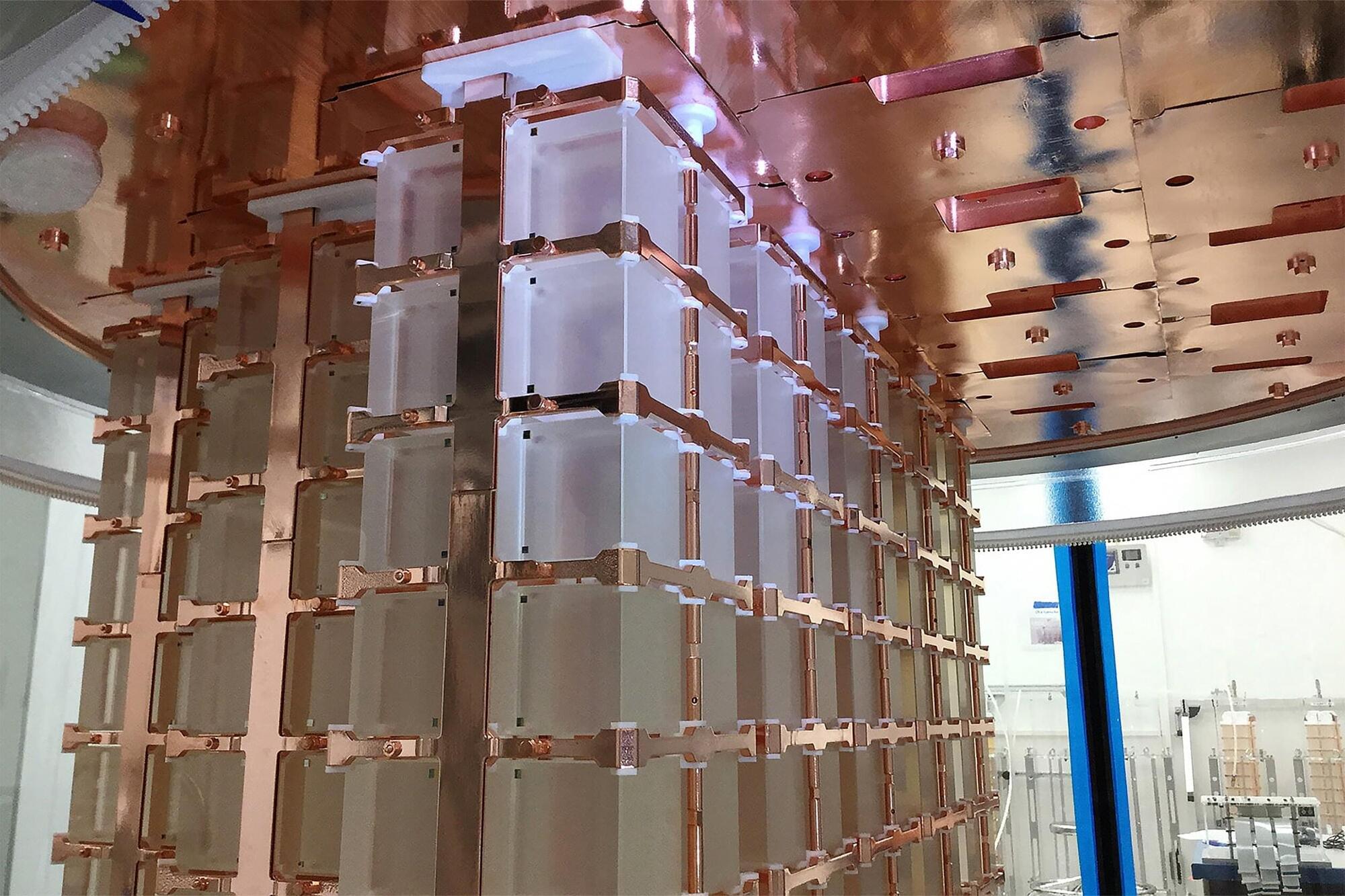

Nuclear batteries — those using the natural decay of radioactive material to create an electric current — have been used in space applications or remote operations such as arctic lighthouses, where changing a battery is difficult or even impossible. The Mars Science Laboratory rover, for example, uses radioisotopic power systems (RPS), which convert heat from radioactive decay into electricity via a thermoelectric generator. Betavolt’s innovation, 3, is a betavoltaic battery that uses beta particles rather than heat as its energy source. (Probably a repost from March 11 2024)

There are additional challenges that hinder the wider usage of these and all types of nuclear batteries, particularly material supply and discomfort with the use of radioactive materials. Yet, the physical and materials science behind this technology could unlock important advances for CO2-free energy and provide power for applications where currently available energy storage technologies are insufficient.

How do betavoltaic batteries work?

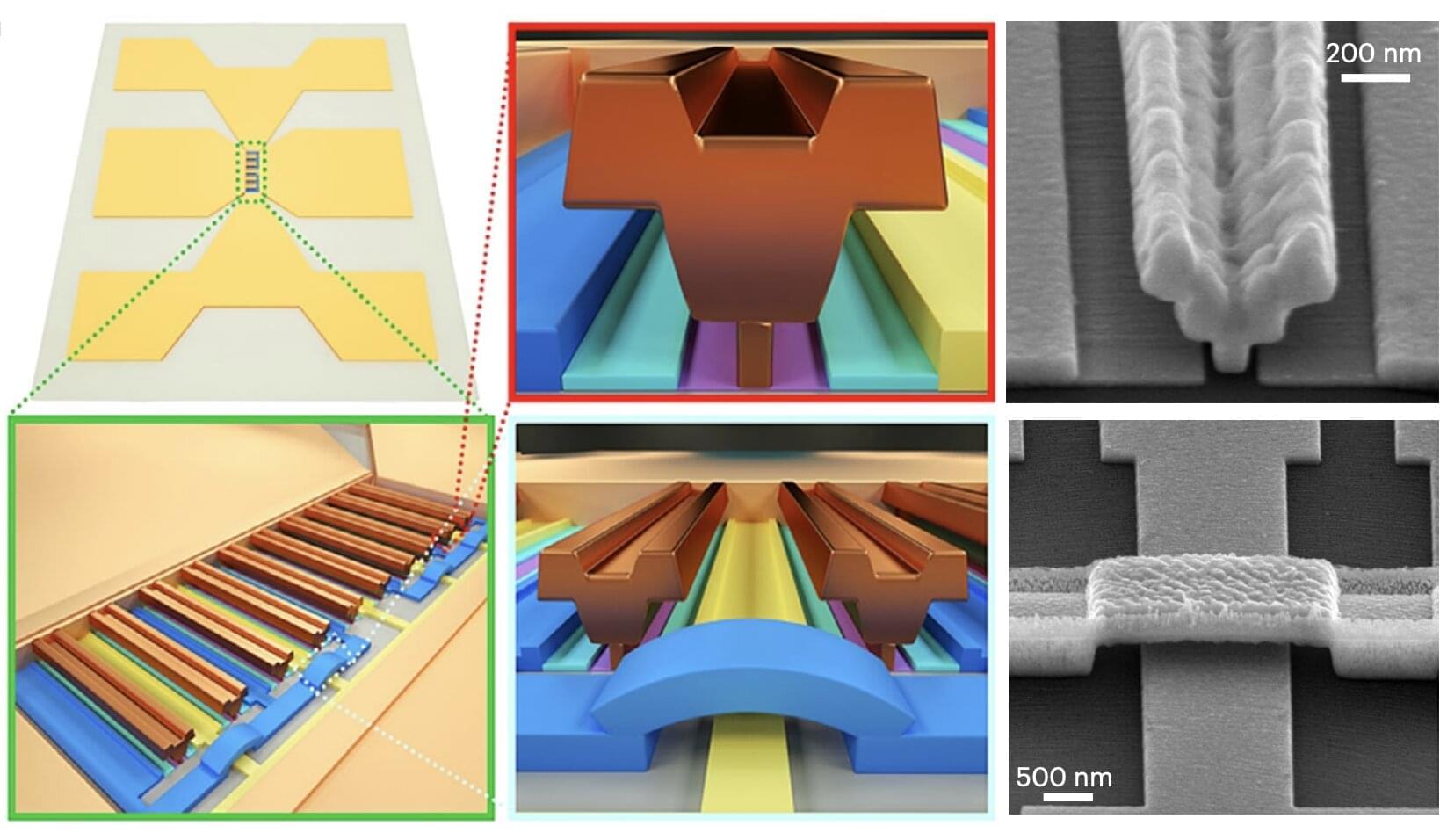

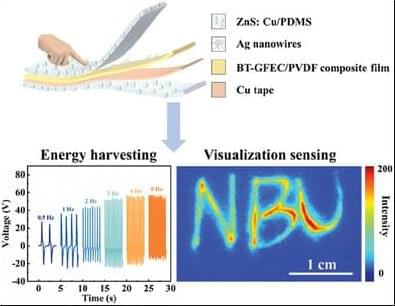

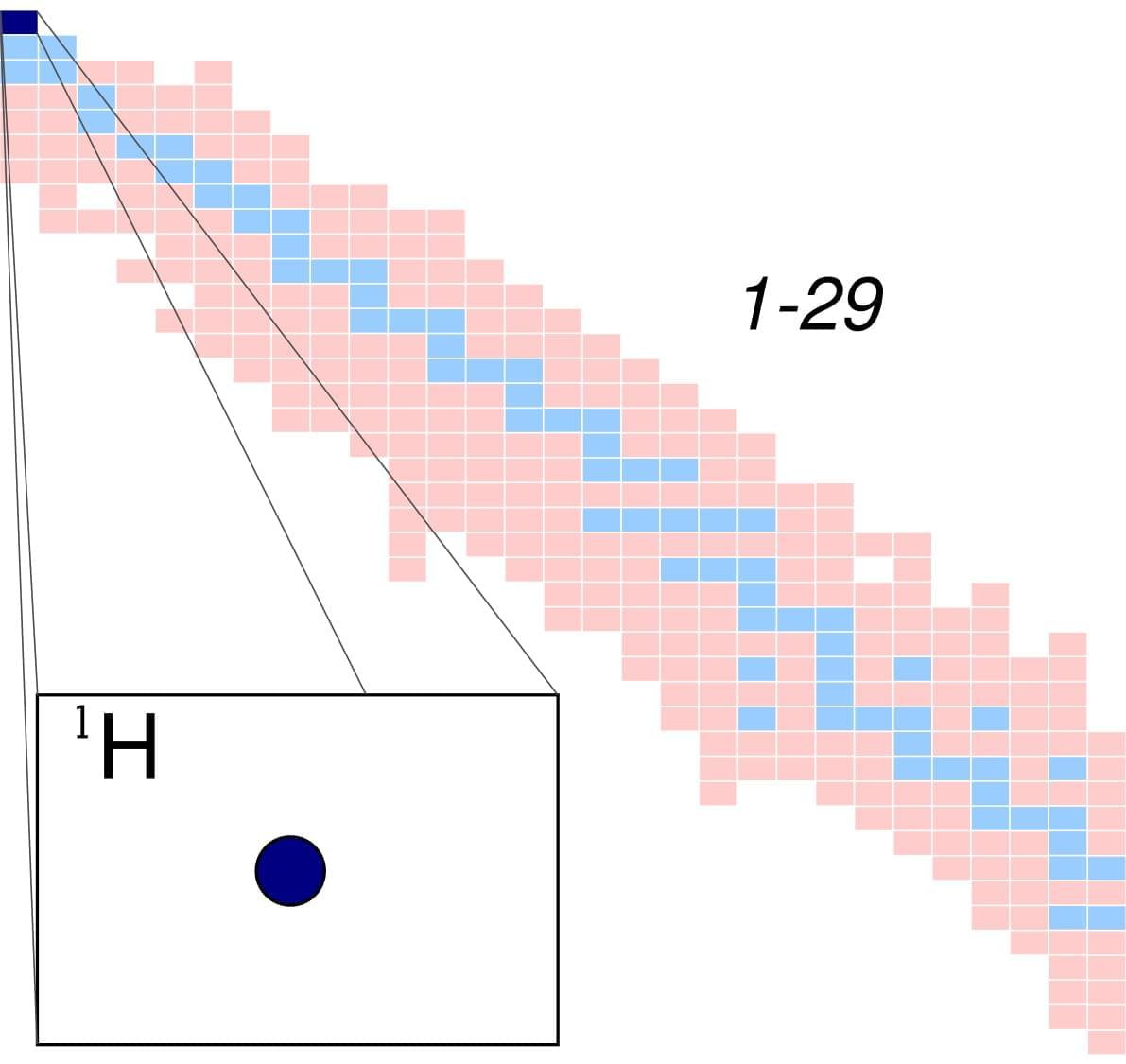

Betavoltaic batteries contain radioactive emitters and semiconductor absorbers. As the emitter material naturally decays, it releases beta particles, or high-speed electrons, which strike the absorber material in the battery, separating electrons from atomic nuclei in the semiconductor absorber. Separation of the resulting electron-hole pairs generates an electric current in the absorber, resulting in electrical power that can be delivered by the battery.