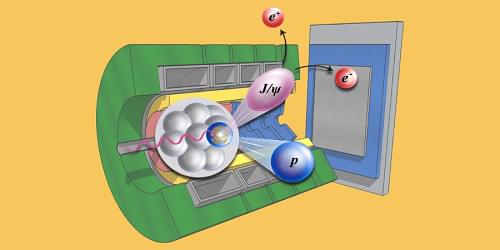

The internal structure of protons bound in nuclei has been probed by studying short-lived particles created when high-energy photons strike nuclei.

Magnets and superconductors go together like oil and water—or so scientists have thought. But a new finding by MIT physicists is challenging this century-old assumption.

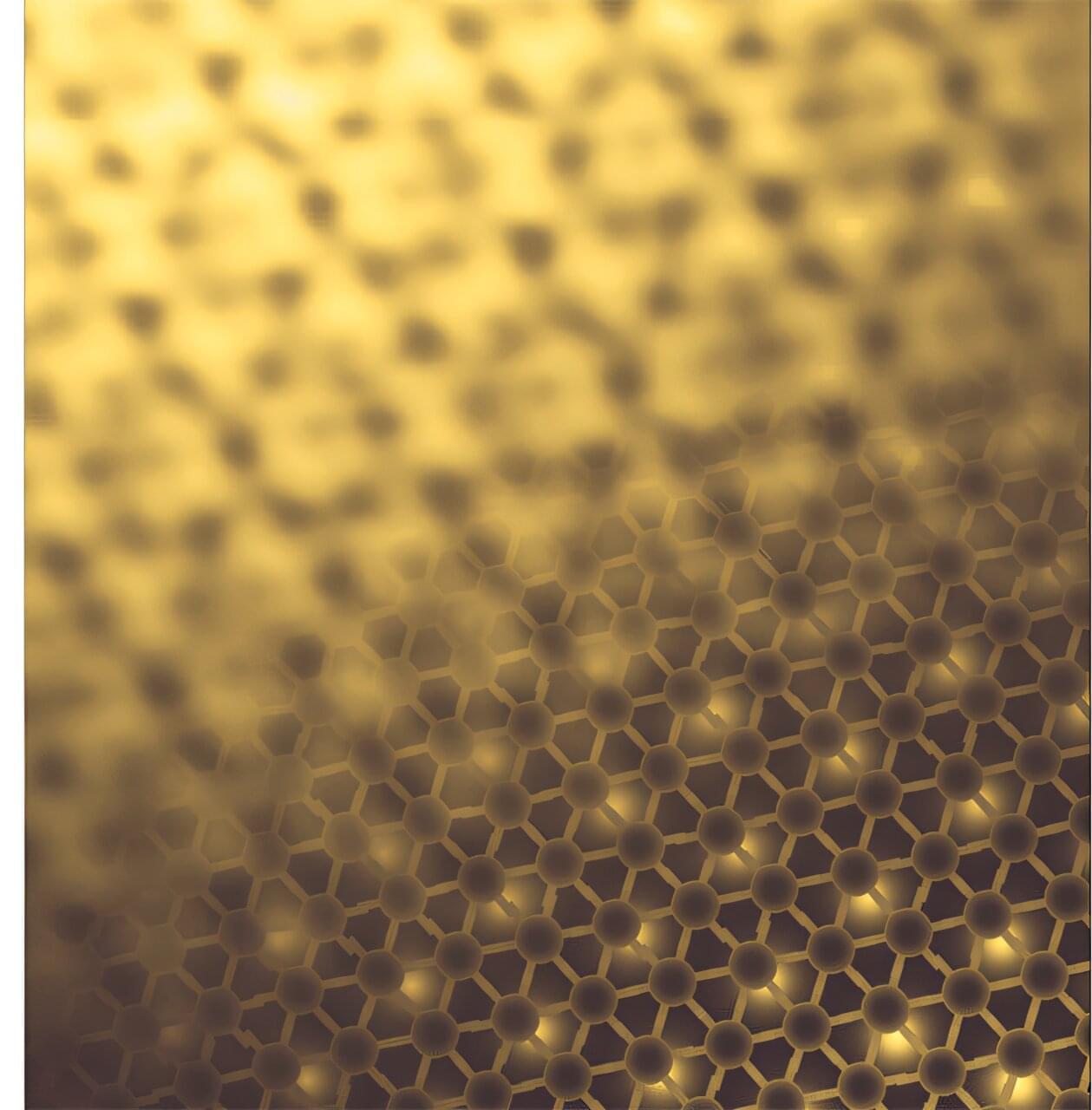

In a paper appearing in the journal Nature, the physicists report that they have discovered a “chiral superconductor”—a material that conducts electricity without resistance, and also, paradoxically, is intrinsically magnetic. What’s more, they observed this exotic superconductivity in a surprisingly ordinary material: graphite, the primary material in pencil lead.

Graphite is made from many layers of graphene—atomically thin, lattice-like sheets of carbon atoms—that are stacked together and can easily flake off when pressure is applied, as when pressing down to write on a piece of paper. A single flake of graphite can contain several million sheets of graphene, which are normally stacked such that every other layer aligns. But every so often, graphite contains tiny pockets where graphene is stacked in a different pattern, resembling a staircase of offset layers.

Manuel Endres, professor of physics at Caltech, specializes in finely controlling single atoms using devices known as optical tweezers. He and his colleagues use the tweezers, made of laser light, to manipulate individual atoms within an array of atoms to study fundamental properties of quantum systems. Their experiments have led to, among other advances, new techniques for erasing errors in simple quantum machines; a new device that could lead to the world’s most precise clocks; and a record-breaking quantum system controlling more than 6,000 individual atoms.

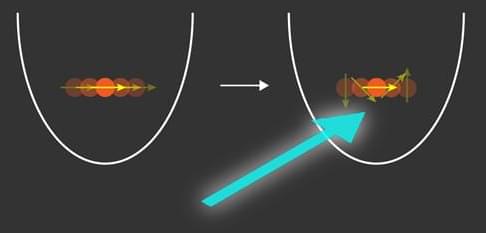

One nagging factor in this line of work has been the normal jiggling motion of atoms, which make the systems harder to control. Now, reporting in the journal Science, the team has flipped the problem on its head and used this atomic motion to encode quantum information.

“We show that atomic motion, which is typically treated as a source of unwanted noise in quantum systems, can be turned into a strength,” says Adam Shaw, a co-lead author on the study along with Pascal Scholl and Ran Finkelstein.

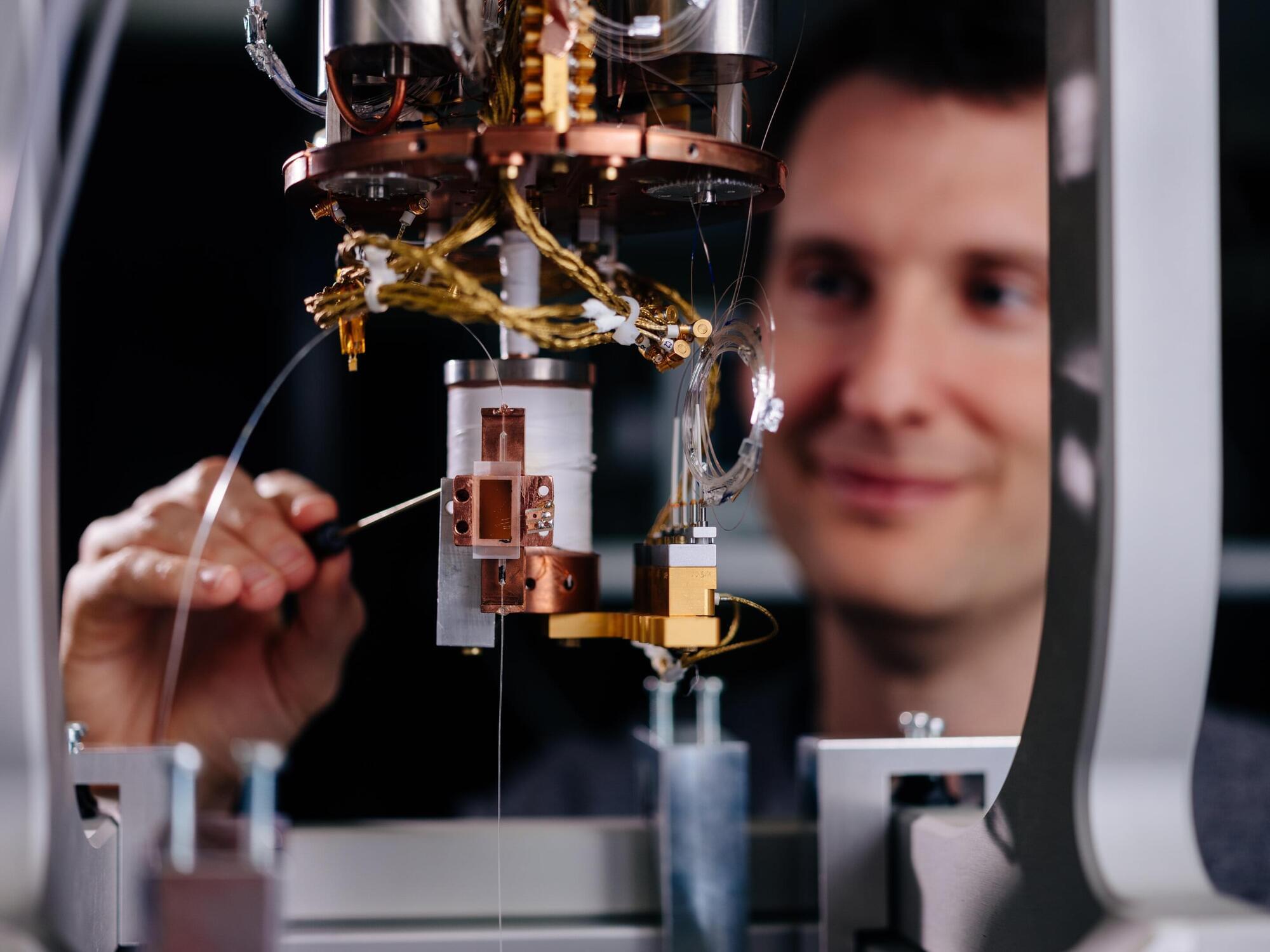

Scientists at Paderborn University have made a further step forward in the field of quantum research: for the first time ever, they have demonstrated a cryogenic circuit (i.e. one that operates in extremely cold conditions) that allows light quanta—also known as photons—to be controlled more quickly than ever before.

Specifically, these scientists have discovered a way of using circuits to actively manipulate light pulses made up of individual photons. This milestone could substantially contribute to developing modern technologies in quantum information science, communication and simulation. The results have now been published in the journal Optica.

Photons, the smallest units of light, are vital for processing quantum information. This often requires measuring a photon’s state in real time and using this information to actively control the luminous flux—a method known as a “feedforward operation.”

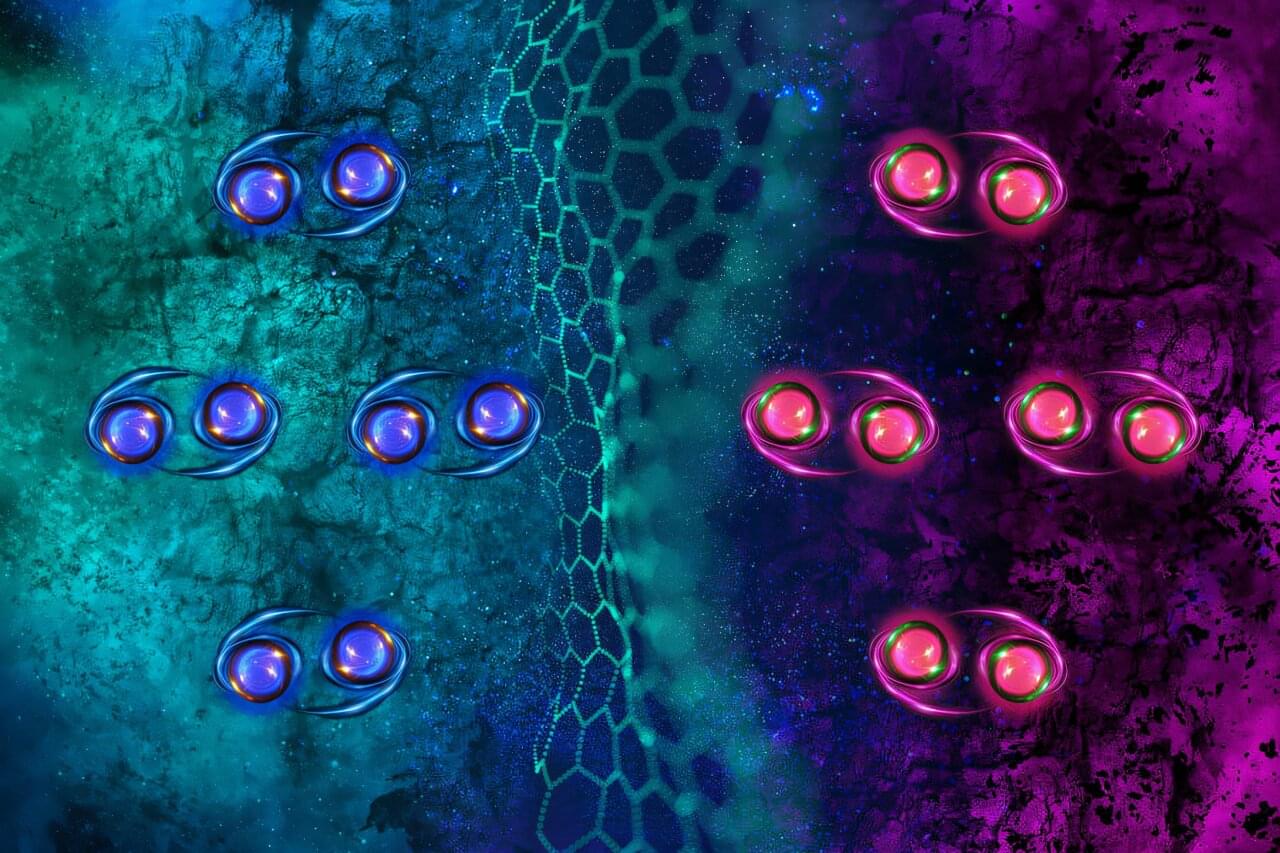

Researchers have made a discovery that could make quantum computing more compact, potentially shrinking essential components 1,000 times while also requiring less equipment. The research is published in Nature Photonics.

A class of quantum computers being developed now relies on light particles, or photons, created in pairs linked or “entangled” in quantum physics parlance. One way to produce these photons is to shine a laser on millimeter-thick crystals and use optical equipment to ensure the photons become linked. A drawback to this approach is that it is too big to integrate into a computer chip.

Now, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) scientists have found a way to address this approach’s problem by producing linked pairs of photons using much thinner materials that are just 1.2 micrometers thick, or about 80 times thinner than a strand of hair. And they did so without needing additional optical gear to maintain the link between the photon pairs, making the overall set-up simpler.

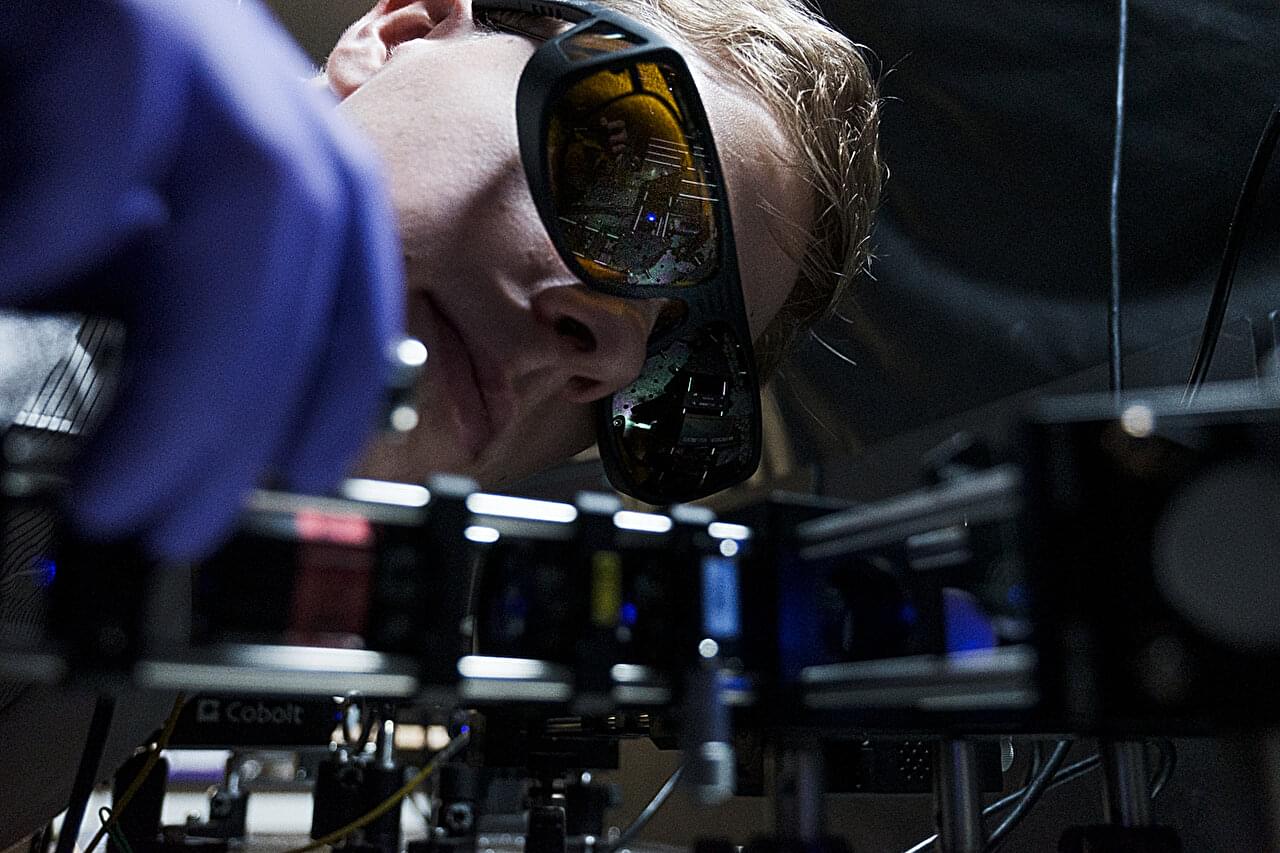

A new laser-based cooling scheme approaches the maximum efficiency that is theoretically achievable.

Much of the progress in 20th-century physics has centered around understanding the interaction between light and matter. The availability of well-controlled light sources—lasers—enabled experimental exploration of controlled light–matter interactions and, specifically, methods to cool atoms close to absolute zero temperatures [1, 2]. Several laser-cooling methods, such as Doppler cooling and resolved sideband cooling, are used routinely to prepare controlled quantum states of atoms. Brennen de Neeve of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich and his colleagues now show just how efficient a laser-cooling process can be [3] (Fig. 1). They demonstrate a laser-cooling method that uses a “spin-dependent force” to transfer motional entropy from the atom into the entropy of its internal degrees of freedom.

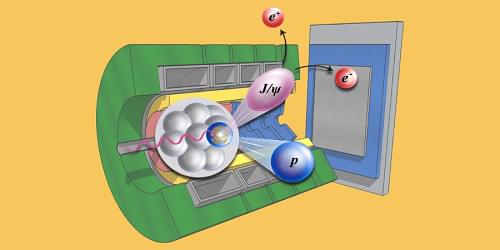

Rutgers University–New Brunswick researchers have discovered a new class of materials—called intercrystals—with unique electronic properties that could power future technologies.

Intercrystals exhibit newly discovered forms of electronic properties that could pave the way for advancements in more efficient electronic components, quantum computing and environmentally friendly materials, the scientists said.

As described in a report in the science journal Nature Materials, the scientists stacked two ultrathin layers of graphene, each a one-atom-thick sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal grid. They twisted them slightly atop a layer of hexagonal boron nitride, a hexagonal crystal made of boron and nitrogen. A subtle misalignment between the layers that formed moiré patterns—patterns similar to those seen when two fine mesh screens are overlaid—significantly altered how electrons moved through the material, they found.

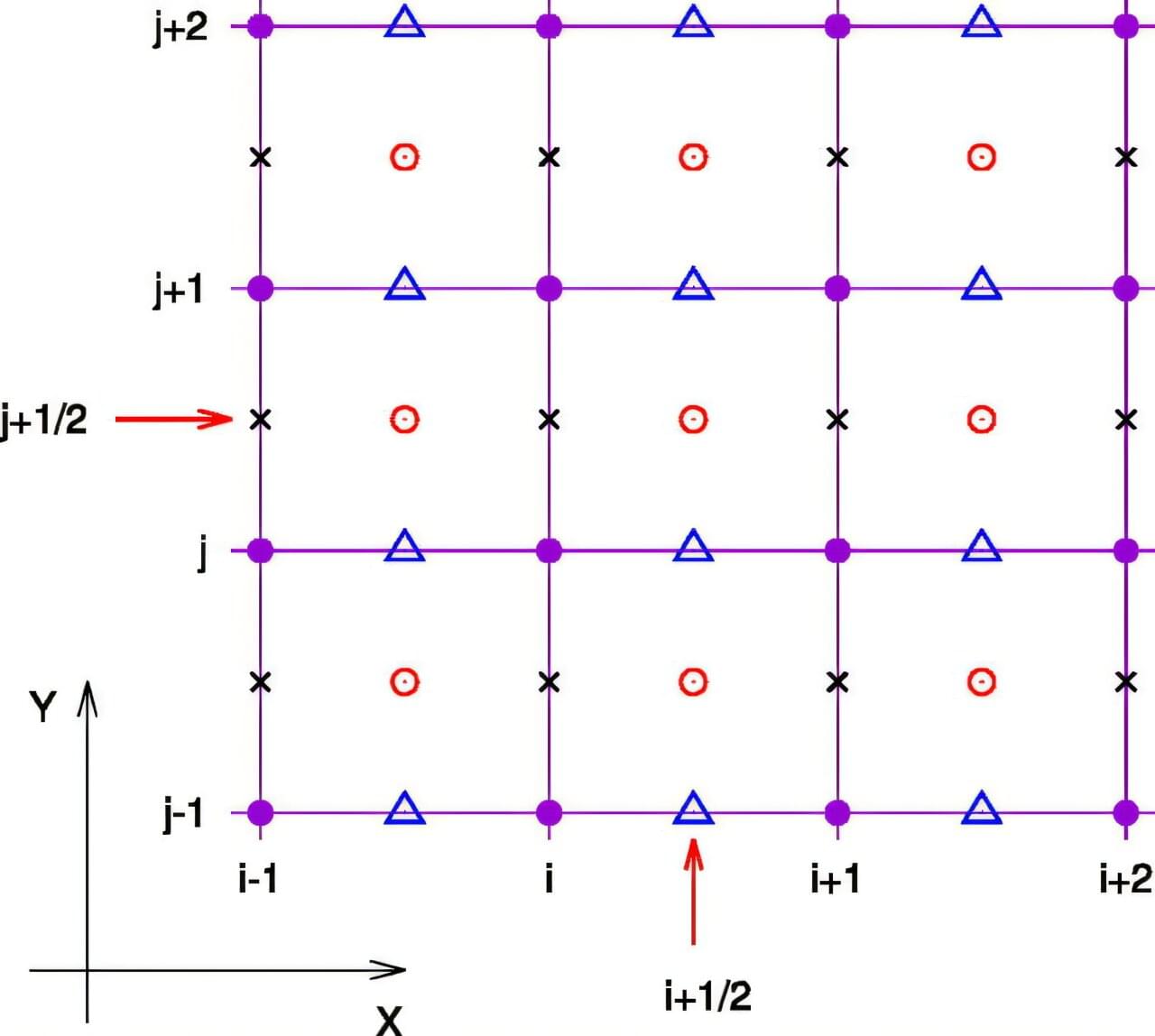

Plasma—the electrically charged fourth state of matter—is at the heart of many important industrial processes, including those used to make computer chips and coat materials.

Simulating those plasmas can be challenging, however, because millions of math operations must be performed for thousands of points in the simulation, many times per second. Even with the world’s fastest supercomputers, scientists have struggled to create a kinetic simulation—which considers individual particles—that is detailed and fast enough to help them improve those manufacturing processes.

Now, a new method offers improved stability and efficiency for kinetic simulations of what’s known as inductively coupled plasmas. The method was implemented in a code developed as part of a private-public partnership between the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and chip equipment maker Applied Materials Inc., which is already using the tool. Researchers from the University of Alberta, PPPL and Los Alamos National Laboratory contributed to the project.

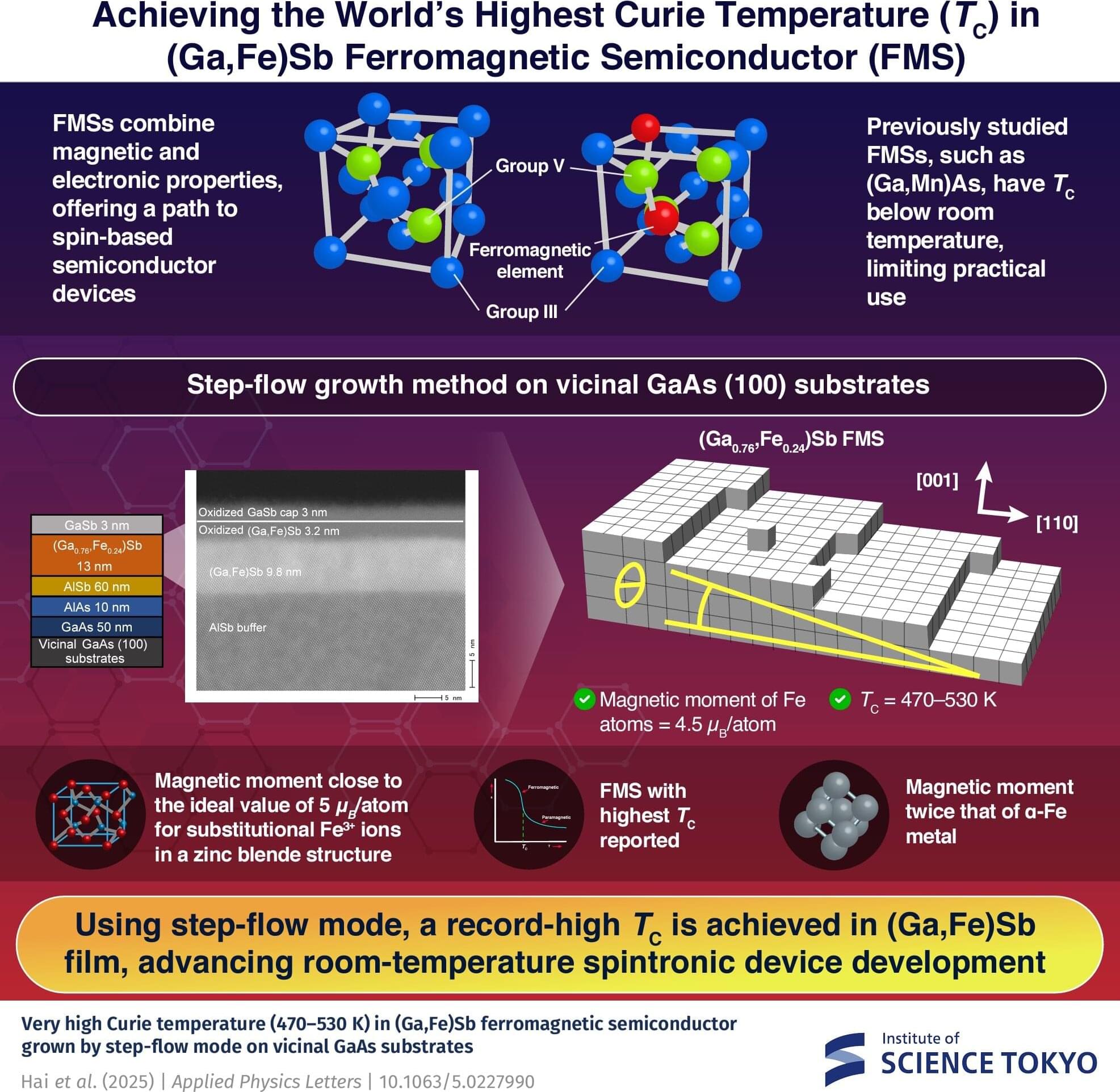

Ferromagnetic semiconductors (FMSs) combine the unique properties of semiconductors and magnetism, making them ideal candidates for developing spintronic devices that integrate both semiconductor and magnetic functionalities. However, one of the key challenges in FMSs has been achieving high Curie temperatures (TC) that enable their stable operation at room temperature.

Though previous studies achieved a TC of 420 K, which is higher than room temperature, it was insufficient for effectively operating the spin functional materials, highlighting the demand for an increase in TC among FMSs. This challenge has been featured among the 125 unsolved questions selected by the journal Science in 2005.

Materials such as (Ga, Mn)As exhibit low TC, limiting their practical use in spintronic devices. While adding Fe to narrow bandgap semiconductors like GaSb seemed promising, incorporating high concentrations of Fe while maintaining crystallinity proved difficult, restricting the attainable TC.