A step towards ultra-precise measurements of antihydrogen.

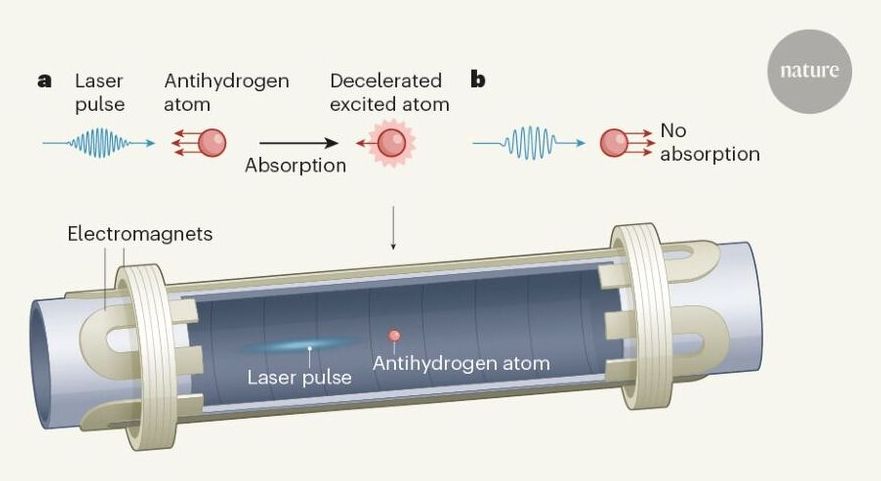

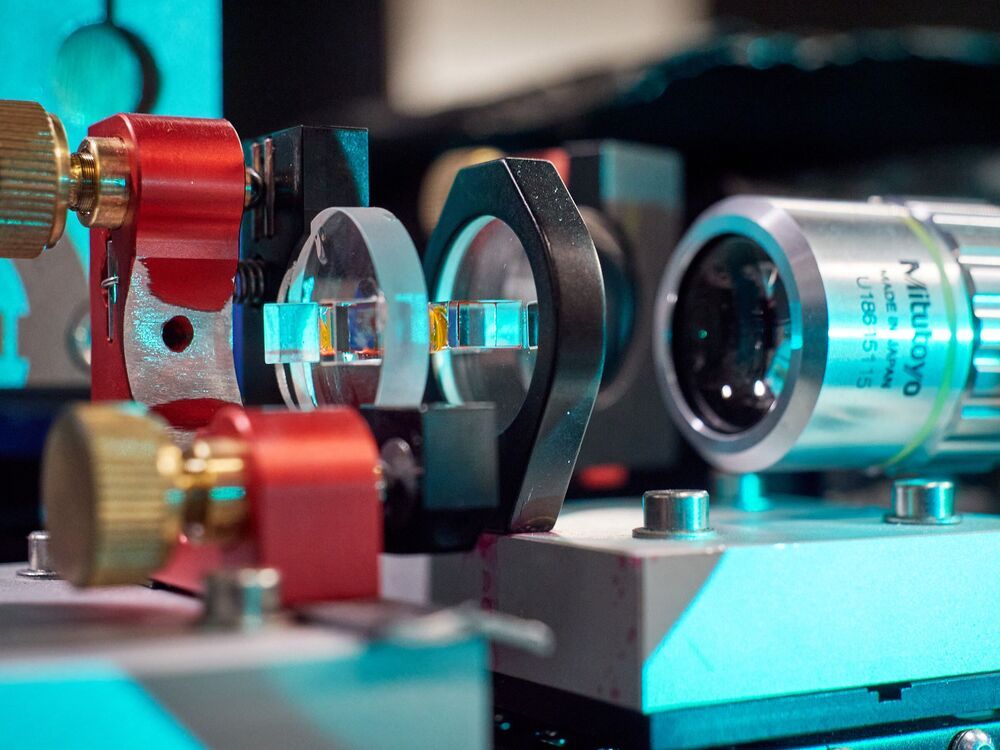

These two constraints are so fundamental that it would be difficult to formulate a consistent understanding of nature without them. Nevertheless, it is worth testing whether they really hold up in ultra-precise measurements carried out using the most modern technologies, because any deviation, however small, would force scientists to radically rethink the basis of our theories of physics. Writing in Nature, Baker et al.1 (members of the ALPHA collaboration) report a major step towards this goal. They have slowed down atoms of antihydrogen — the antimatter counterpart of hydrogen — to unprecedentedly low velocities by bathing them in a beam of ultraviolet laser light. This could allow measurements of the atoms to be made with exceptionally high precision.

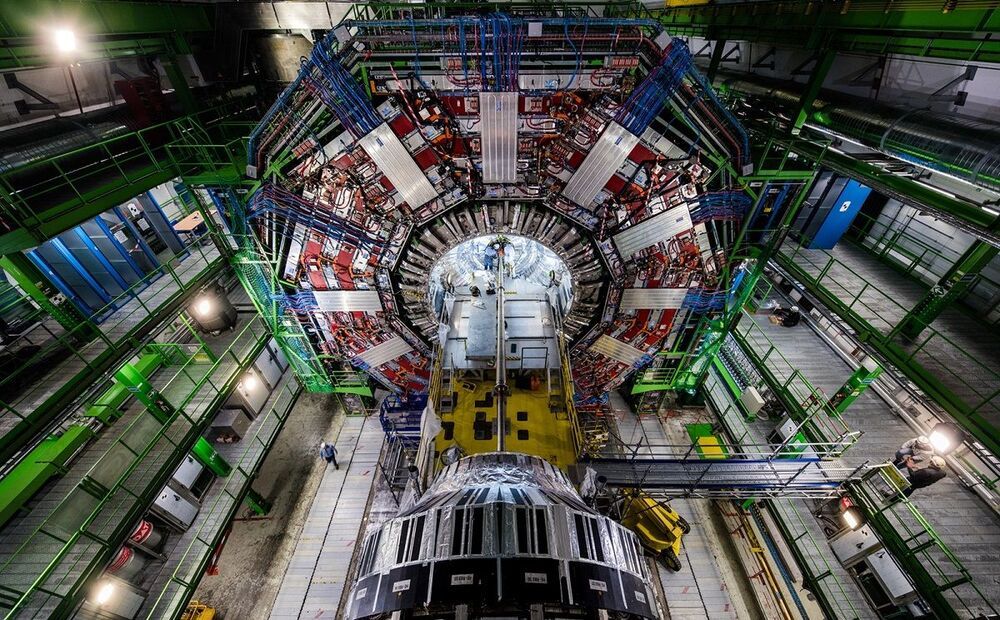

Antihydrogen is the simplest stable atom that consists only of antimatter particles, namely an antiproton and an antielectron (a positron). Measurements of antihydrogen therefore provide an ideal way to test the symmetry between matter and antimatter, but such experiments present formidable obstacles. In 1995, 11 antihydrogen atoms were produced from reactions in a particle accelerator at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, and hurtled down a 10-metre-long vacuum tube at nine-tenths of the speed of light2. Each atom existed for barely a few tens of nanoseconds before being destroyed by striking a particle detector.

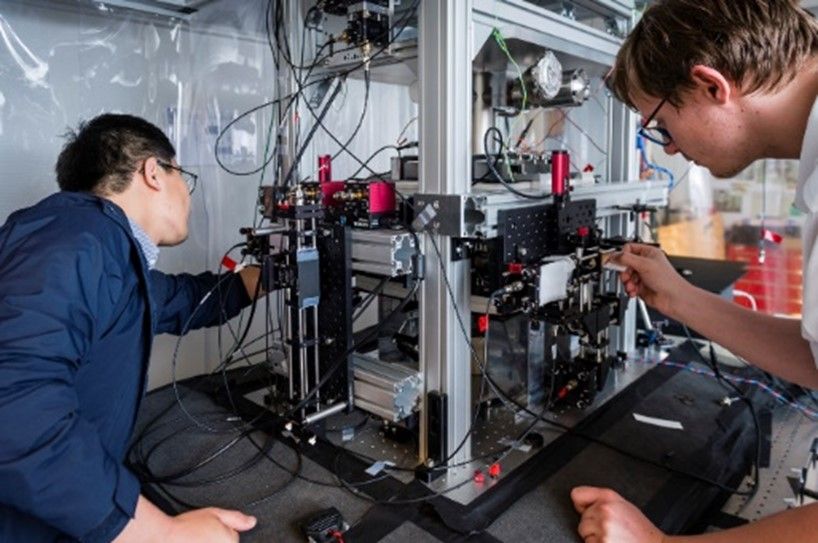

Much of the ensuing research into antihydrogen has involved inventing new ways of producing samples of increasingly slower-moving atoms. This was eventually achieved by confining and mixing clouds of antiprotons and positrons in magnetic fields that acted as ion traps to produce antihydrogen atoms. The atoms were then confined by another complex configuration of magnetic fields that acted as a neutral-atom trap3,4. The ALPHA collaboration at CERN’s Antiproton Decelerator facility can now routinely trap 1000 antihydrogen atoms for many hours in this way. This has allowed an atomic frequency of antihydrogen, which corresponds to the energy of a characteristic atomic transition, to be measured5 with a fractional precision of 2 parts in 1012. No deviation from the corresponding frequency of hydrogen was observed, which is exactly the outcome expected from CPT symmetry.