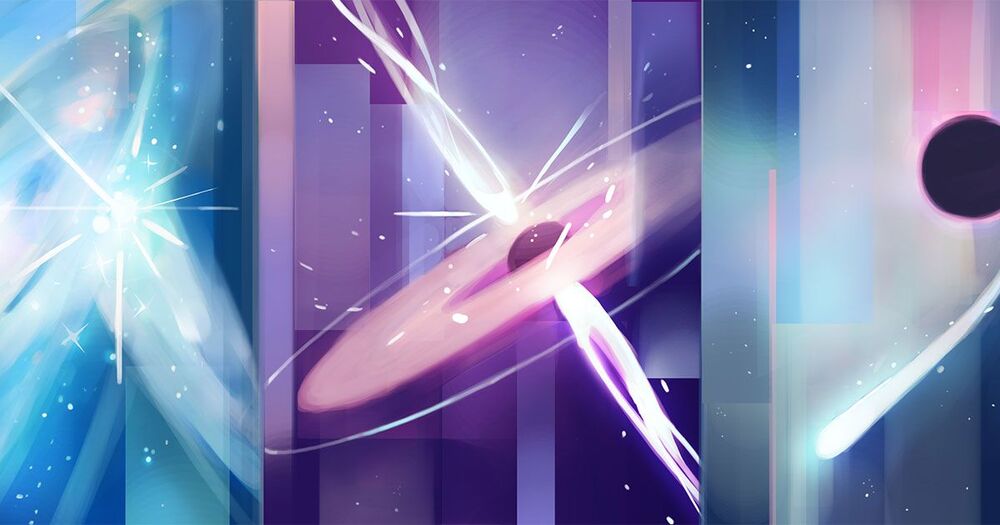

Starburst galaxies, active galactic nuclei and tidal disruption events (from left) have emerged as top candidates for the dominant source of ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays.

In the 1930s, the French physicist Pierre Auger placed Geiger counters along a ridge in the Alps and observed that they would sometimes spontaneously click at the same time, even when they were up to 300 meters apart. He knew that the coincident clicks came from cosmic rays, charged particles from space that bang into air molecules in the sky, triggering particle showers that rain down to the ground. But Auger realized that for cosmic rays to trigger the kind of enormous showers he was seeing, they must carry fantastical amounts of energy — so much that, he wrote in 1939, “it is actually impossible to imagine a single process able to give to a particle such an energy.”

Upon constructing larger arrays of Geiger counters and other kinds of detectors, physicists learned that cosmic rays reach energies at least 100000 times higher than Auger supposed.

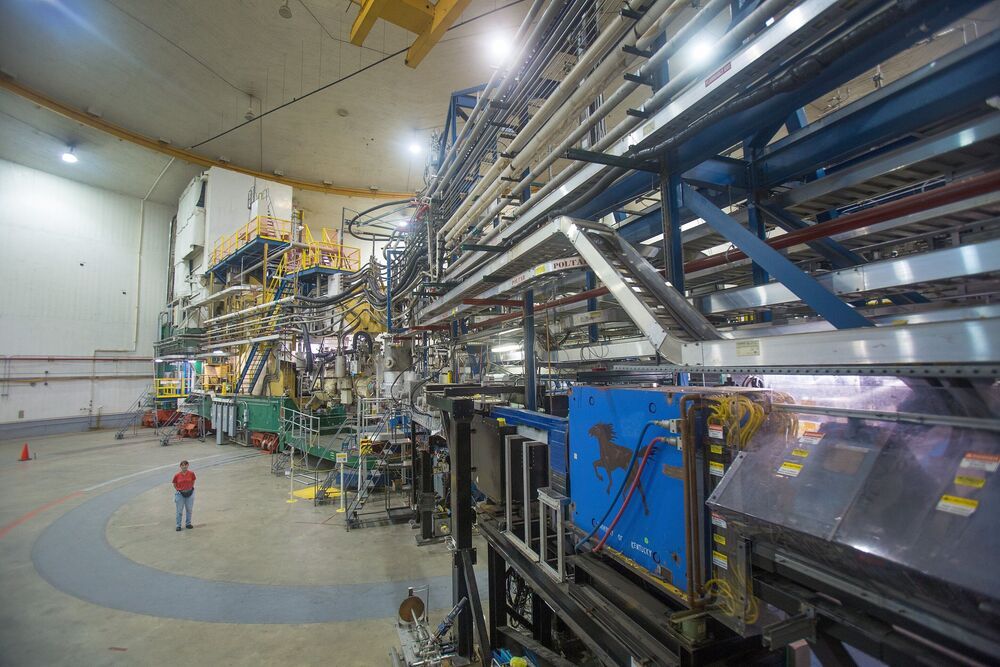

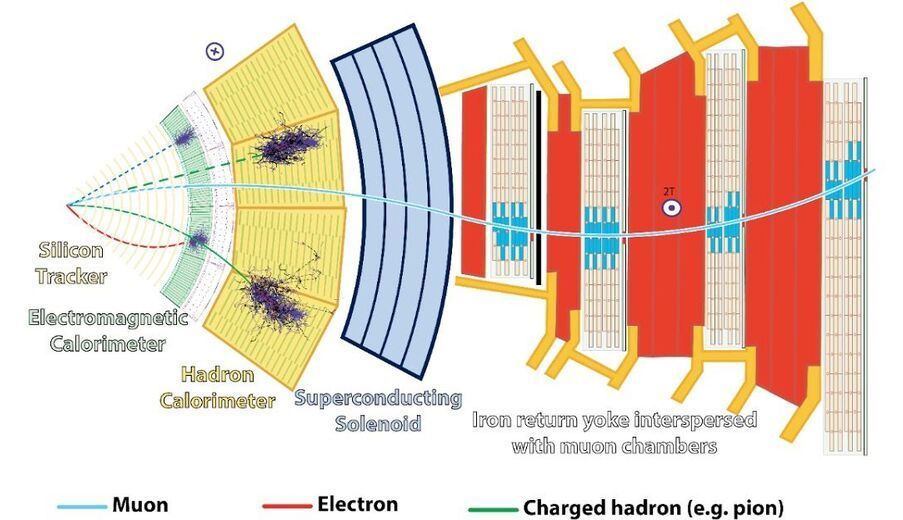

A cosmic ray is just an atomic nucleus — a proton or a cluster of protons and neutrons. Yet the rare ones known as “ultrahigh-energy” cosmic rays have as much energy as professionally served tennis balls. They’re millions of times more energetic than the protons that hurtle around the circular tunnel of the Large Hadron Collider in Europe at 99.9999991% of the speed of light. In fact, the most energetic cosmic ray ever detected, nicknamed the “Oh-My-God particle,” struck the sky in 1991 going something like 99.99999999999999999999951% of the speed of light, giving it roughly the energy of a bowling ball dropped from shoulder height onto a toe. “You would have to build a collider as large as the orbit of the planet Mercury to accelerate protons to the energies we see,” said Ralph Engel, an astrophysicist at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany and the co-leader of the world’s largest cosmic-ray observatory, the Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina.