Stellar nurseries are a hotbed for heists.

These stellar nurseries are densely populated places, where hundreds of thousands of stars often reside in the same volume of space that the Sun inhabits on its own. Violent interactions, in which stars exchange energy, occur frequently, but not for long. After a few million years, the groups of stars dissipate, populating the Milky Way with more stars.

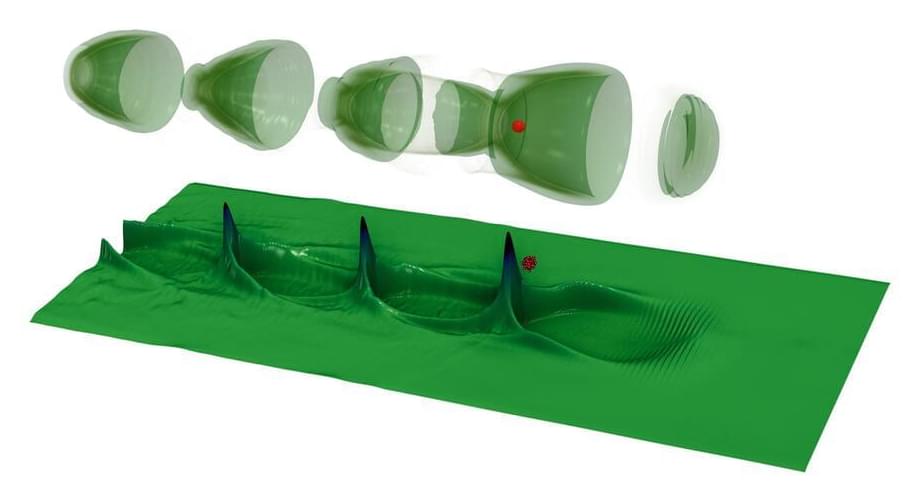

Our new paper, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, shows how massive stars in such stellar nurseries can steal planets away from each other — and what the signs of such theft are.

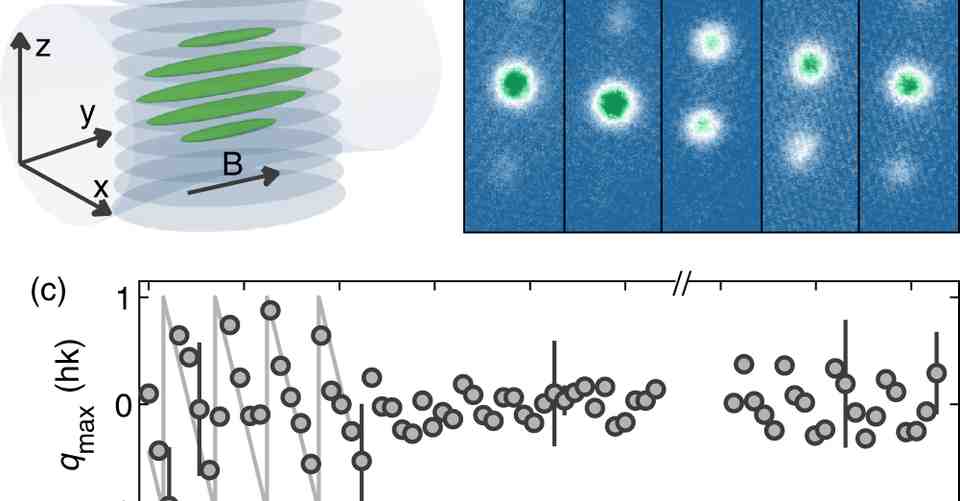

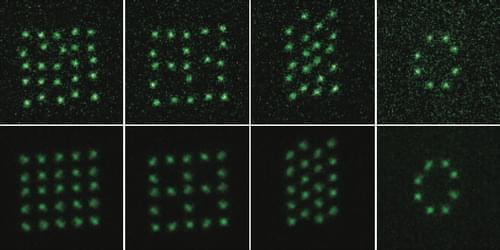

Almost immediately after young stars are born, planetary systems begin to form around them. We have had indirect evidence of this for more than 30 years. Observations of the light from young stars display an unexpected excess of infrared radiation. This was (and still is) explained as originating from small dust particles (100th of a centimeter) orbiting the star in a disc of material. It is from these dust particles that planets are (eventually) formed.