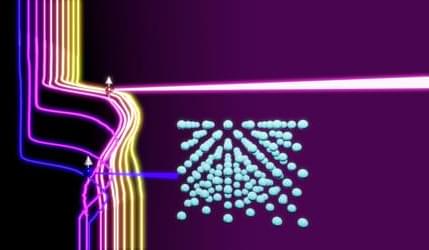

All its mechanical components are now together for the first time.

Good news! The largest digital camera in the world is nearly ready to be mounted on its telescope. At the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, technicians are finishing up the largest digital camera in the world. The camera will be shipped to Chile and mounted on a telescope located in the Andes. The project was started a couple of years ago.

Even though the camera isn’t finished yet, all of its mechanical parts have now, for the first time, been assembled into a visually appealing framework.

Jacqueline ramseyer orrell/slac national accelerator laboratory.

At the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, technicians are finishing up the largest digital camera in the world. The camera will be shipped to Chile and mounted on a telescope located in the Andes. The project was started a couple of years ago.