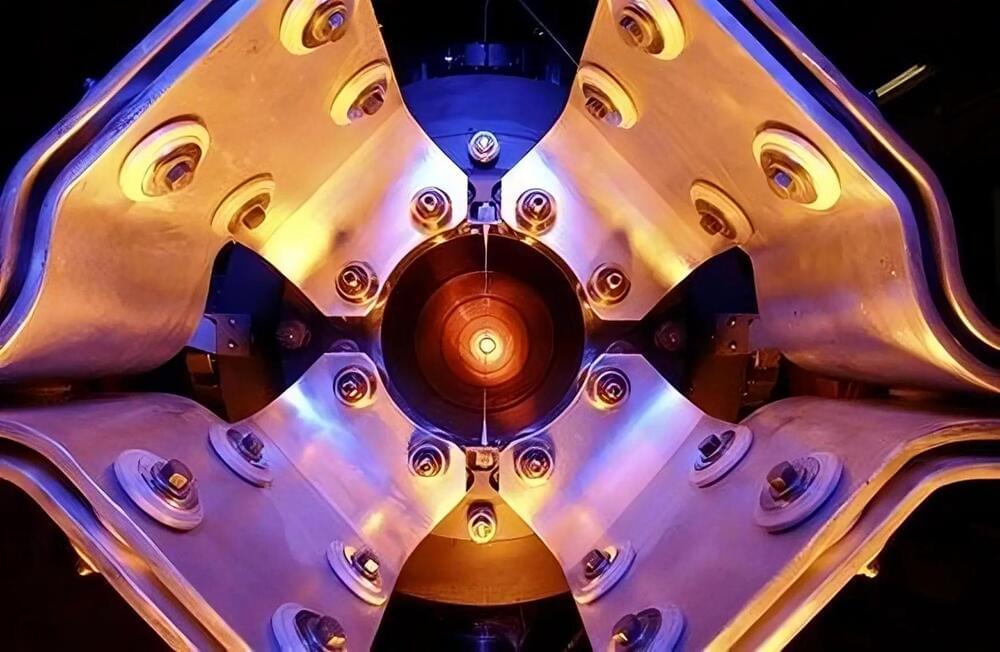

Providing increased resistance to outside interference, topological qubits create a more stable foundation than conventional qubits. This increased stability allows the quantum computer to perform computations that can uncover solutions to some of the world’s toughest problems.

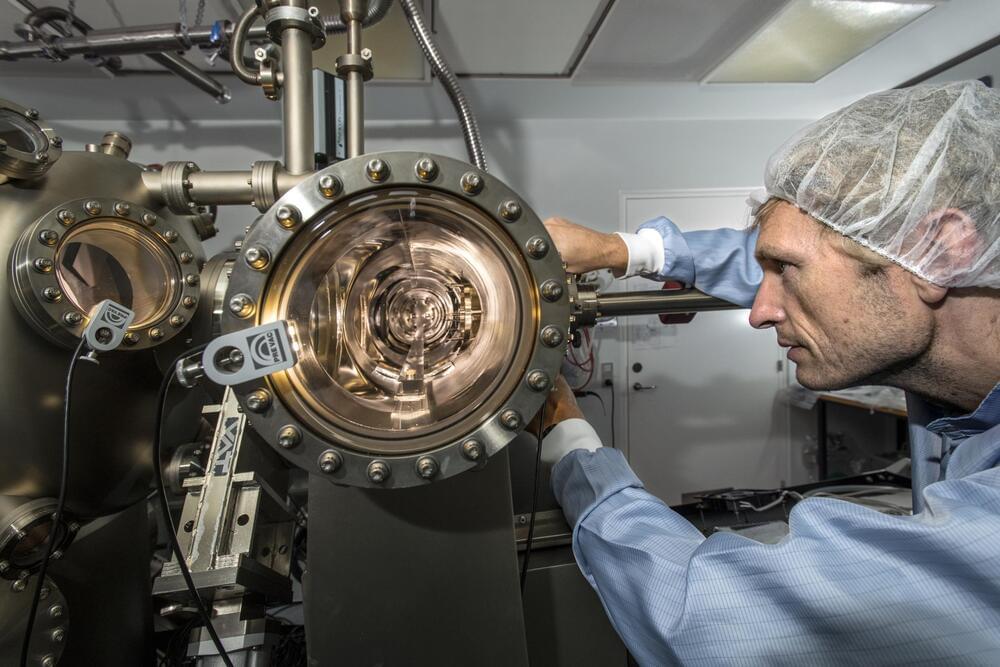

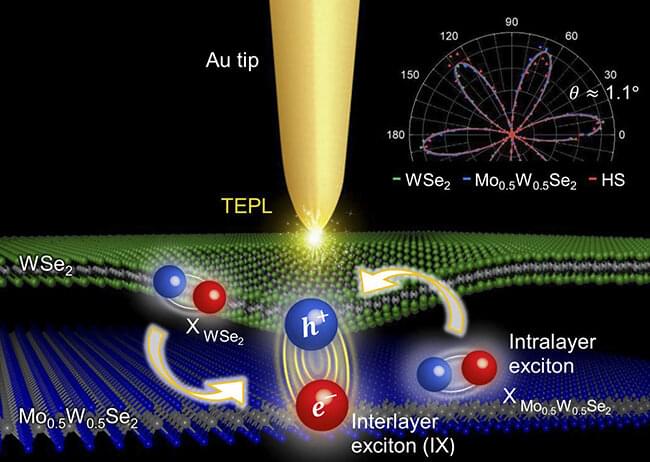

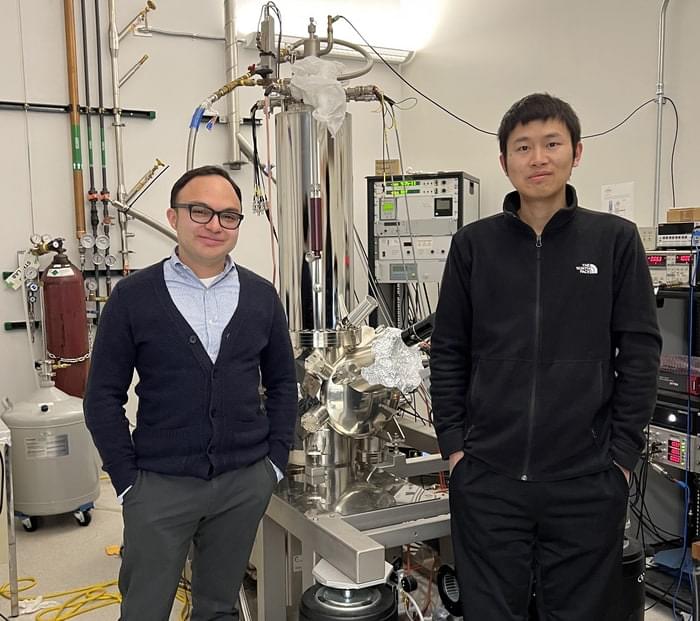

While qubits can be developed in a variety of ways, the topological qubit will be the first of its kind, requiring innovative approaches from design through development. Materials containing the properties needed for this new technology cannot be found in nature—they must be created. Microsoft brought together experts from condensed matter physics, mathematics, and materials science to develop a unique approach producing specialized crystals with the properties needed to make the topological qubit a reality.