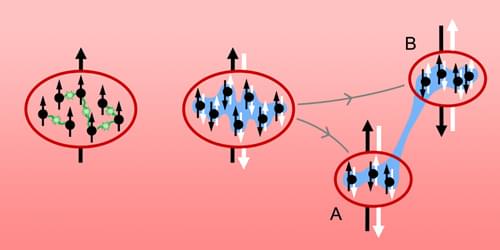

A new demonstration involving hundreds of entangled atoms tests Schrödinger’s interpretation of Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky’s classic thought experiment.

In 1935, Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen (EPR) presented an argument that they claimed implies that quantum mechanics provides an incomplete description of reality [1]. The argument rests on two assumptions. First, if the value of a physical property of a system can be predicted with certainty, without disturbance to the system, then there is an “element of reality” to that property, meaning it has a value even if it isn’t measured. Second, physical processes have effects that act locally rather than instantaneously over a distance. John Bell subsequently proposed a way to experimentally test these “local realism” assumptions [2], and so-called Bell tests have since invalidated them for systems of a few small particles, such as electrons or photons [3].