Scientists have caught fast-moving hydrogen atoms—the keys to countless biological and chemical reactions—in action.

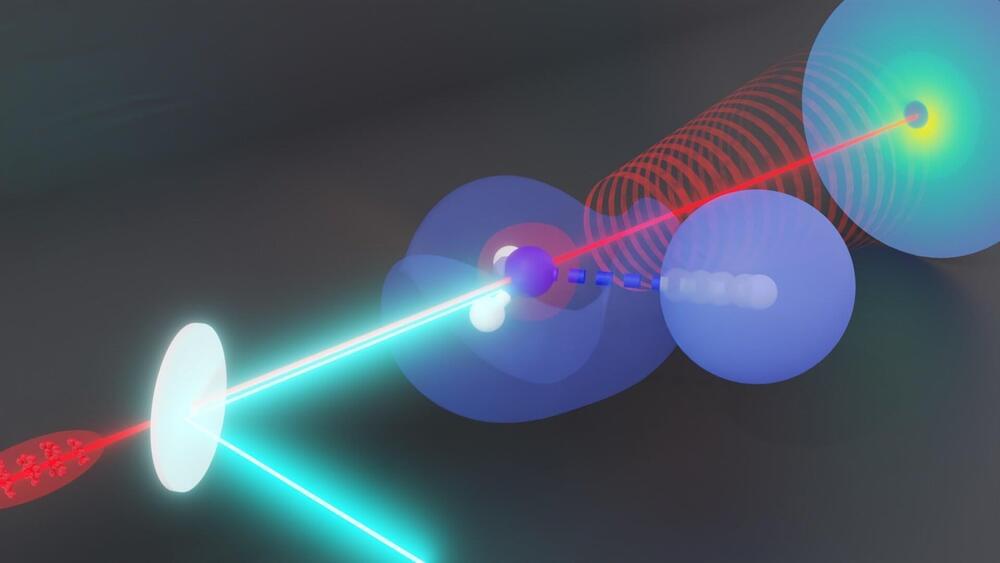

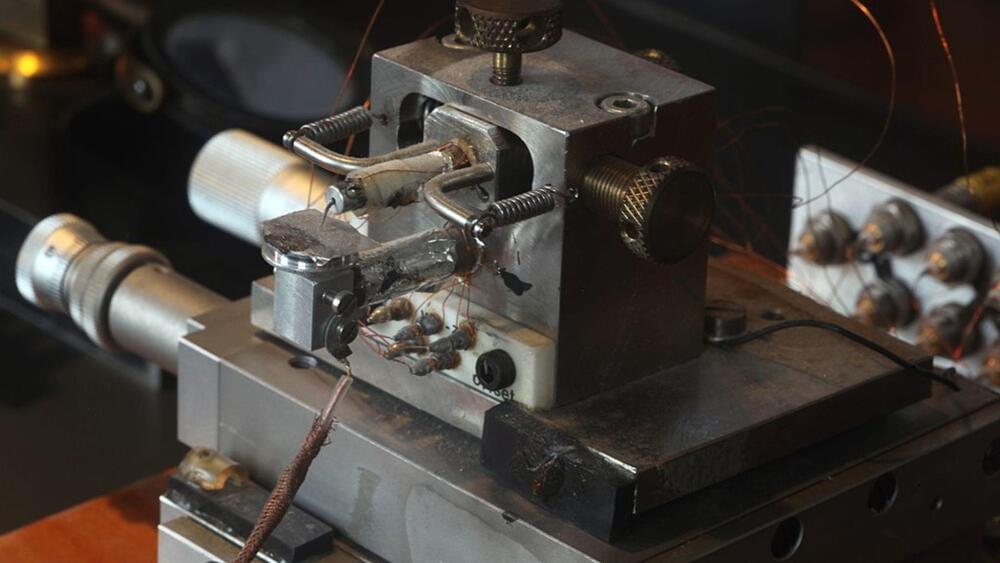

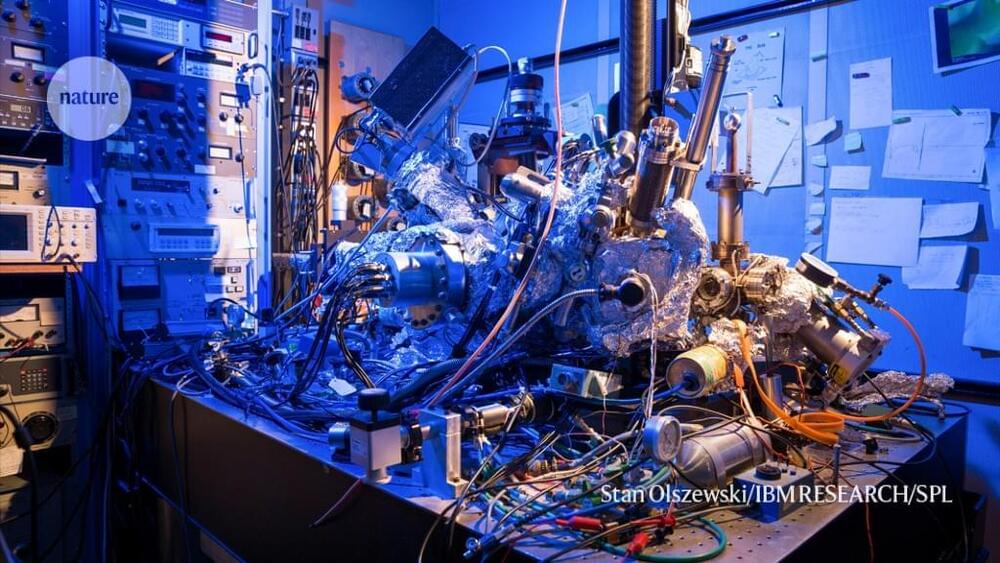

A team led by researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University used ultrafast electron diffraction (UED) to record the motion of hydrogen atoms within ammonia molecules. Others had theorized they could track hydrogen atoms with electron diffraction, but until now nobody had done the experiment successfully.

The results, published in Physical Review Letters, leverage the strengths of high-energy Megaelectronvolt (MeV) electrons for studying hydrogen atoms and proton transfers, in which the singular proton that makes up the nucleus of a hydrogen atom moves from one molecule to another.