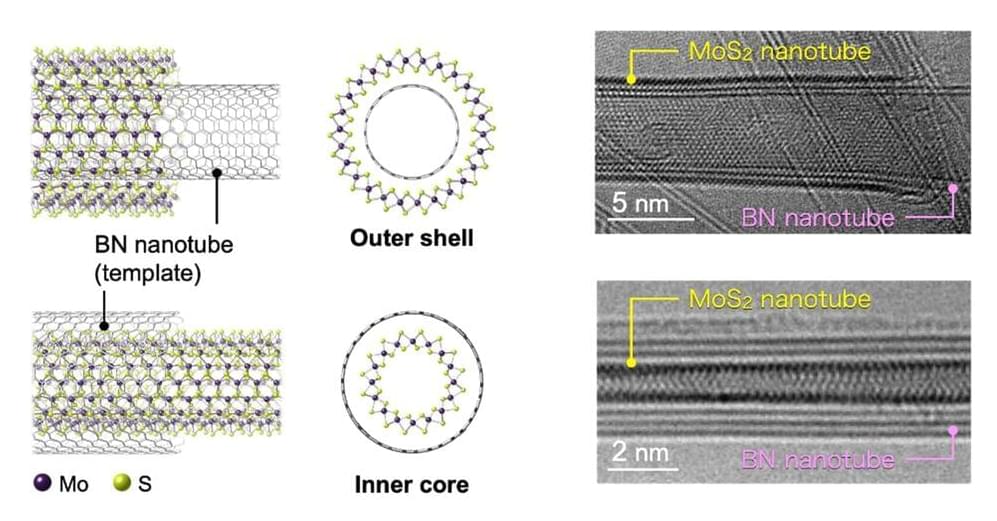

Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have engineered a range of new single-walled transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) nanotubes with different compositions, chirality, and diameters by templating off boron-nitride nanotubes. They also realized ultra-thin nanotubes grown inside the template, and successfully tailored compositions to create a family of new nanotubes. The ability to synthesize a diverse range of structures offers unique insights into their growth mechanism and novel optical properties.

The work is published in the journal Advanced Materials.

The carbon nanotube is a wonder of nanotechnology. Made by rolling up an atomically thin sheet of carbon atoms, it has exceptional mechanical strength and electrical conductivity among a range of other exotic optoelectronic properties, with potential applications in semiconductors beyond the silicon age.