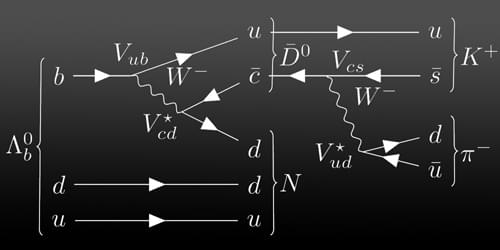

Researchers predict a large “CP” violation for the decay of a baryon that contains a bottom quark, a finding that has implications for how physicists understand the Universe.

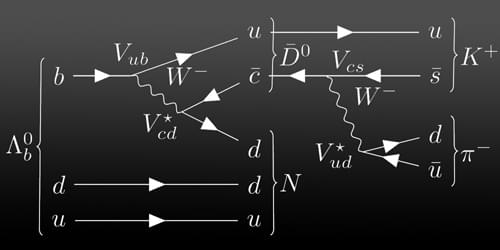

Researchers have developed an atom-diffraction imaging method with micrometer spatial resolution, which may allow new applications in material characterization.

Microscopy with atoms offers new possibilities in the study of surfaces and two-dimensional (2D) materials [1]. Atom beams satisfy the most important requirements for microscopic probing: they can achieve high contrast and surface-specificity while doing little damage to the sample. A subtype of atomic microscopy—atomic-diffraction imaging—obtains measurements in reciprocal, or momentum, space, which is ideal for studying the surfaces of large and uniform crystalline samples. However, scientists developing this technique face challenges in achieving micrometer-scale spatial resolutions that would allow the study of polycrystalline materials, nonuniform 2D materials, and other surfaces without long-range order.

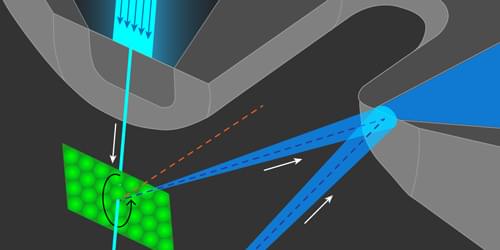

Thought to make up 85% of matter in the universe, dark matter is nonluminous and its nature is not well understood. While normal matter absorbs, reflects, and emits light, dark matter cannot be seen directly, making it harder to detect. A theory called “self-interacting dark matter,” or SIDM, proposes that dark matter particles self-interact through a dark force, strongly colliding with one another close to the center of a galaxy.

In work published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, a research team led by Hai-Bo Yu, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Riverside, reports that SIDM simultaneously can explain two astrophysics puzzles in opposite extremes.

“The first is a high-density dark matter halo in a massive elliptical galaxy,” Yu said. “The halo was detected through observations of strong gravitational lensing, and its density is so high that it is extremely unlikely in the prevailing cold dark matter theory. The second is that dark matter halos of ultra-diffuse galaxies have extremely low densities and they are difficult to explain by the cold dark matter theory.”

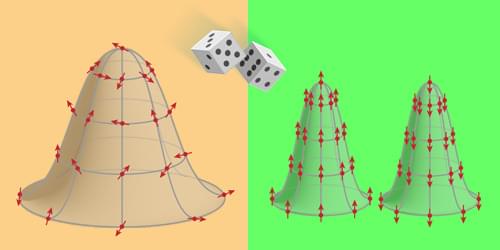

A proposed model unites quantum theory with classical gravity by assuming that states evolve in a probabilistic way, like a game of chance.

Physicists’ best theory of matter is quantum mechanics, which describes the discrete (quantized) behavior of microscopic particles via wave equations. Their best theory of gravity is general relativity, which describes the continuous (classical) motion of massive bodies via space-time curvature. These two highly successful theories appear fundamentally at odds over the nature of space-time: quantum wave equations are defined on a fixed space-time, but general relativity says that space-time is dynamic—curving in response to the distribution of matter. Most attempts to solve this tension have focused on quantizing gravity, with the two leading proposals being string theory and loop quantum gravity. But new theoretical work by Jonathan Oppenheim at University College London proposes an alternative: leave gravity as a classical theory and couple it to quantum theory through a probabilistic mechanism [1].

A massive hole opened up in the Sun’s atmosphere over the weekend, measuring more than 60 times the diameter of the Earth across at its peak.

Coronal holes like this one, imaged by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory, occur when the Sun’s magnetic field suddenly allows a huge stream of the star’s upper atmosphere to pour out in the form of solar wind.

Over a short period of time, these highly energized particles can eventually make their way to us and — if powerful enough — wreak havoc on satellites in the Earth’s orbit. In rare instances, they can even mess with the electrical grid back on the ground.

As someone who never lived in the extreme northern latitudes of Earth, I always found it exciting when I heard auroras might be visible farther south. I would always crane my eyes skyward, hoping I could see those ghostly dancing lights, almost trying to wish them into existence. Alas, I was never that lucky. Though as we approach solar maximum in 2025, we ought not to only get excited about seeing auroras, but perhaps also ask: What could a powerful geomagnetic storm do to our technological infrastructure?

Geomagnetic storms can be triggered by either coronal mass ejections, giant bubbles of plasma erupting from the surface of the sun, or very powerful solar flares. It’s because these events can accelerate particles to extremely fast speeds. And when some of those particles hit the Earth’s magnetic field, this generates what we see as brilliant auroras — however, those particles can also damage satellite equipment and even harm astronauts in orbit.

A truly gigantic magnetic storm has not affected the Earth in well over one hundred years — and since then, technology has changed quite significantly. Satellite communications, air travel and the power grid have been brought into existence, and they all can be impacted by these events. Yet, scientists aren’t quite sure what, exactly, would happen to the integral technological components of society if a major solar storm shrouded Earth with charged particle showers.

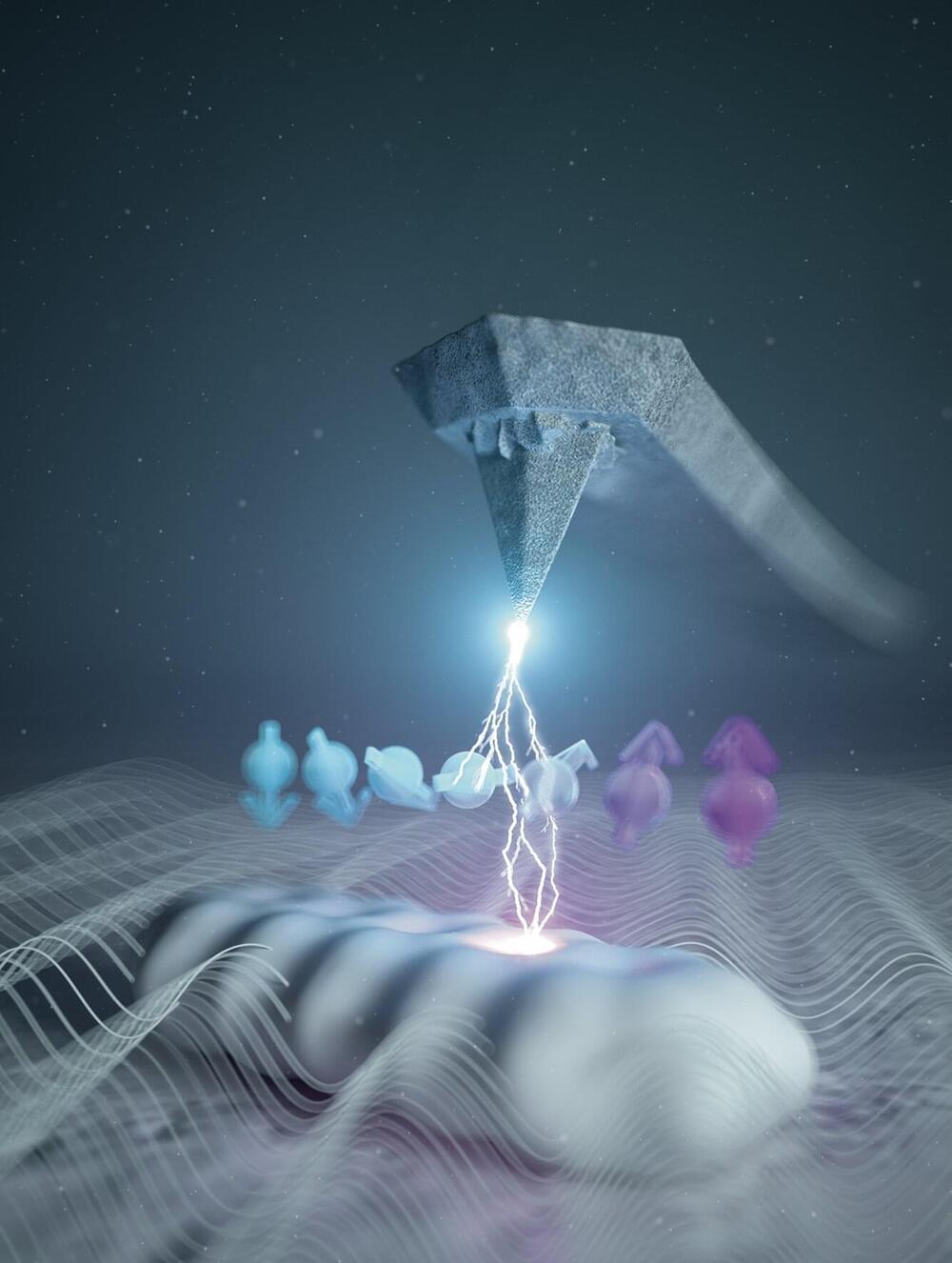

Physicists at the University of Regensburg have found a way to manipulate the quantum state of individual electrons using a microscope with atomic resolution. The results of the study have now been published in the journal Nature.

We, and everything around us, consist of molecules. The molecules are so tiny that even a speck of dust contains countless numbers of them. It is now routinely possible to precisely image such molecules with an atomic force microscope, which works quite differently from an optical microscope: it is based on sensing tiny forces between a tip and the molecule under study.

Using this type of microscope, one can even image the internal structure of a molecule. Although one can watch the molecule this way, this does not imply knowing all its different properties. For instance, it is already very hard to determine which kind of atoms the molecule consists of.

A radical theory that consistently unifies gravity and quantum mechanics while preserving Einstein’s classical concept of spacetime is announced today in two papers published simultaneously by UCL (University College London) physicists.

Modern physics is founded upon two pillars: quantum theory on the one hand, which governs the smallest particles in the universe, and Einstein’s theory of general relativity on the other, which explains gravity through the bending of spacetime. But these two theories are in contradiction with each other and a reconciliation has remained elusive for over a century.

Challenging the status quo: a new theoretical approach.

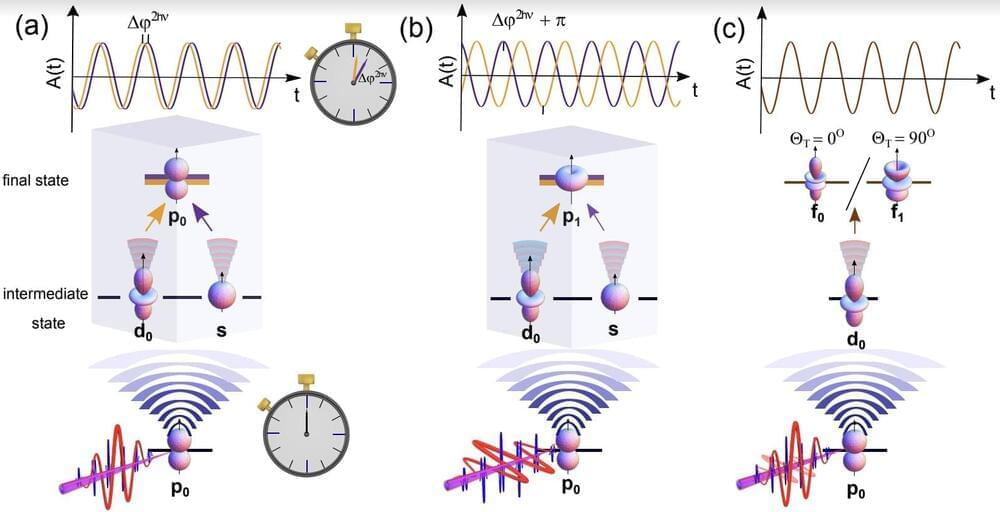

The field of attosecond physics was established with the mission of exploring light–matter interactions at unprecedented time resolutions. Recent advancements in this field have allowed physicists to shed new light on the quantum dynamics of charge carriers in atoms and molecules.

A technique that has proved particularly valuable for conducting research in this field is RABBITT (i.e., the Reconstruction of Attosecond Beating By Interference of Two-photon Transitions). This promising tool was initially used to characterize ultrashort laser pulses, as part of a research effort that won this year’s Nobel Prize, yet it has since also been employed to measure other ultrafast physical phenomena.

Researchers at East China Normal University and Queen’s University Belfast recently built on the RABBITT technique to distinctly measure individual contributions in photoionization. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, introduces a new highly promising method for conducting attosecond physics research.