Harvard’s breakthrough in quantum computing features a new logical quantum processor with 48 logical qubits, enabling large-scale algorithm execution on an error-corrected system. This development, led by Mikhail Lukin, represents a major advance towards practical, fault-tolerant quantum computers.

In quantum computing, a quantum bit or “qubit” is one unit of information, just like a binary bit in classical computing. For more than two decades, physicists and engineers have shown the world that quantum computing is, in principle, possible by manipulating quantum particles – be they atoms, ions or photons – to create physical qubits.

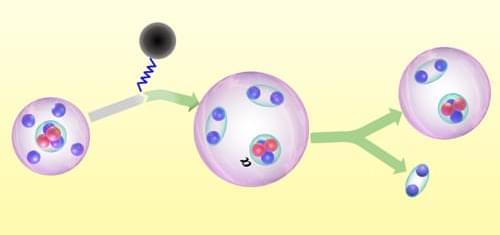

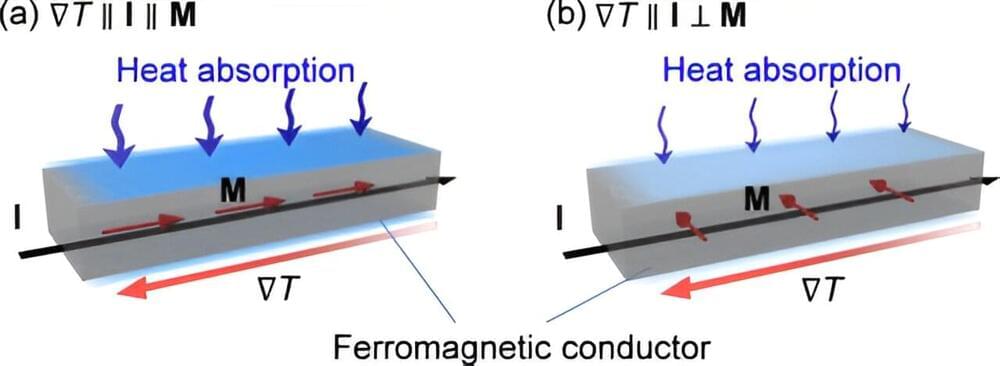

But successfully exploiting the weirdness of quantum mechanics for computation is more complicated than simply amassing a large-enough number of physical qubits, which are inherently unstable and prone to collapse out of their quantum states.