Heat is the enemy of quantum uncertainty. By arranging light-absorbing molecules in an ordered fashion, physicists in Japan have maintained the critical, yet-to-be-determined state of electron spins for 100 nanoseconds near room temperature.

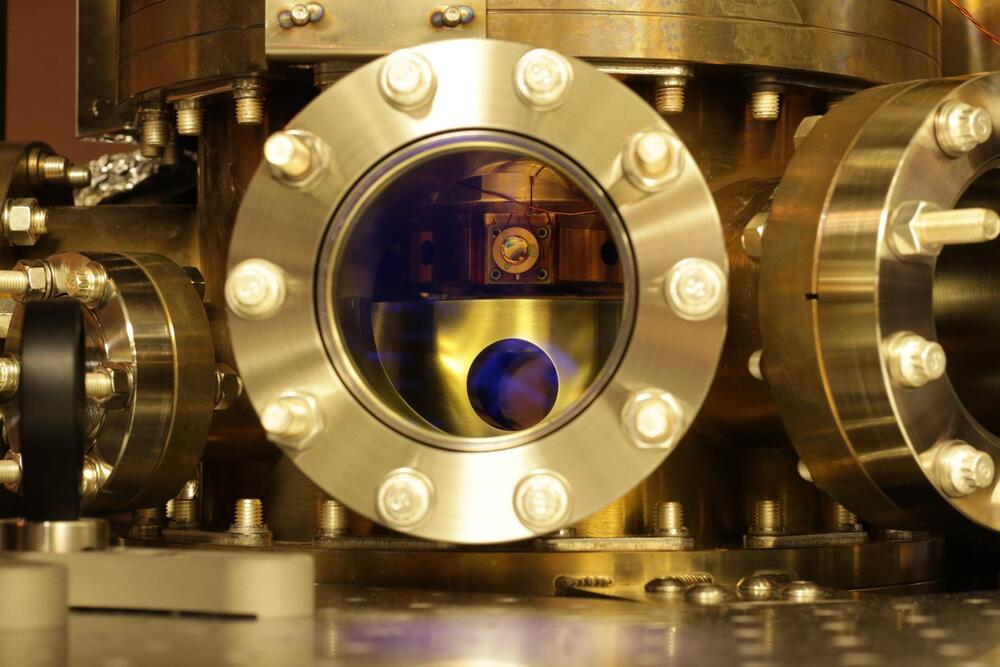

The innovation could have a profound impact on progress in developing quantum technology that doesn’t rely on the bulky and expensive cooling equipment currently needed to keep particles in a so-called ‘coherent’ form.

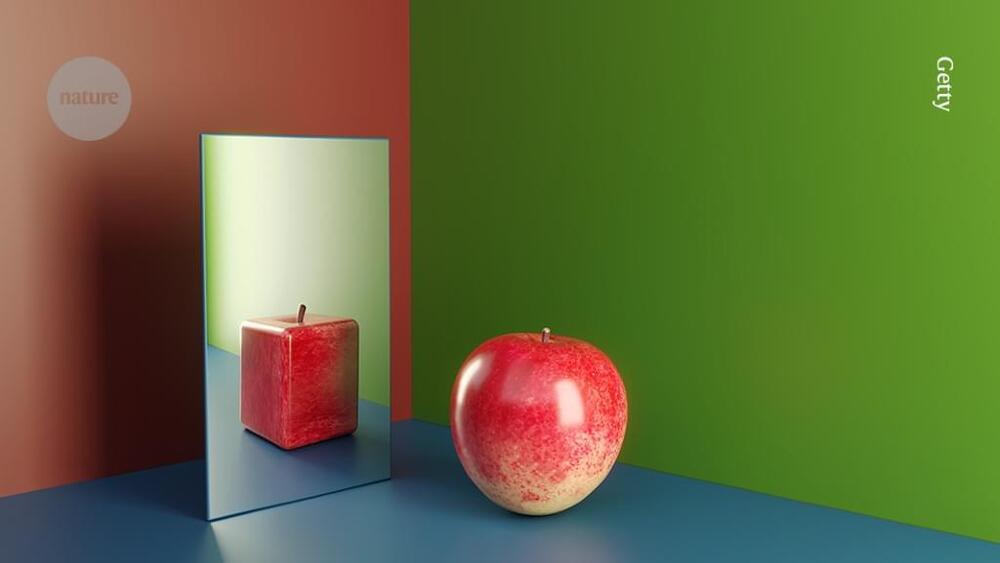

Unlike the way we describe objects in our day-to-day living, which have qualities like color, position, speed, and rotation, quantum descriptions of objects involve something less settled. Until their characteristics are locked in place with a quick look, we have to treat objects as if they are smeared over a wide space, spinning in different directions, yet to adopt a simple measurement.