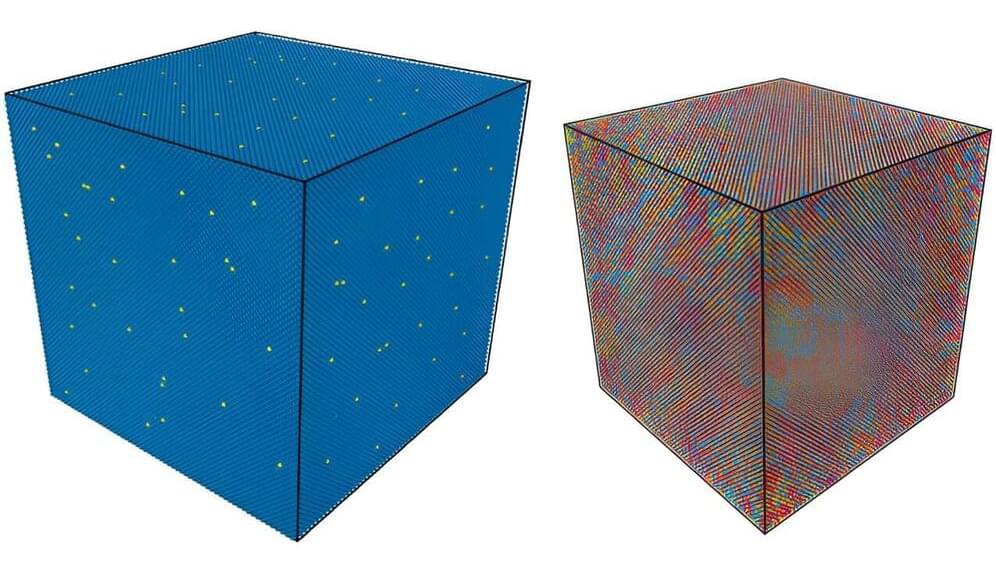

The concept of short-range order (SRO)—the arrangement of atoms over small distances—in metallic alloys has been underexplored in materials science and engineering. But the past decade has seen renewed interest in quantifying it, since decoding SRO is a crucial step toward developing tailored high-performing alloys, such as stronger or heat-resistant materials.

Understanding how atoms arrange themselves is no easy task and must be verified using intensive lab experiments or computer simulations based on imperfect models. These hurdles have made it difficult to fully explore SRO in metallic alloys.

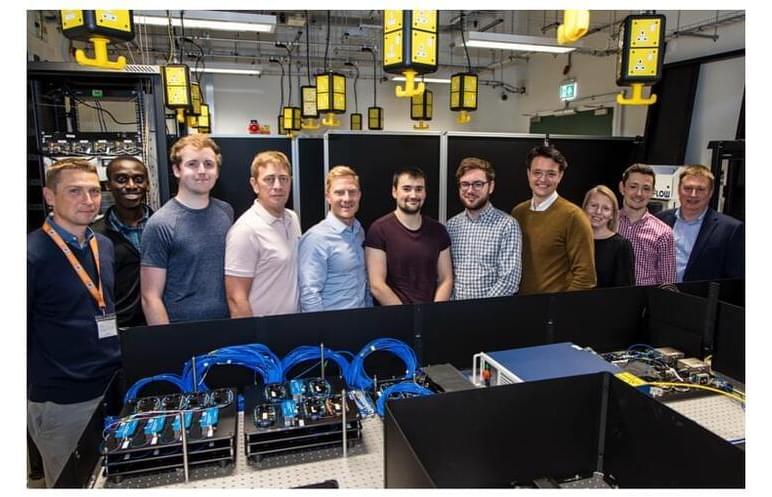

But Killian Sheriff and Yifan Cao, graduate students in MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DMSE), are using machine learning to quantify, atom by atom, the complex chemical arrangements that make up SRO. Under the supervision of Assistant Professor Rodrigo Freitas, and with the help of Assistant Professor Tess Smidt in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, their work was recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.