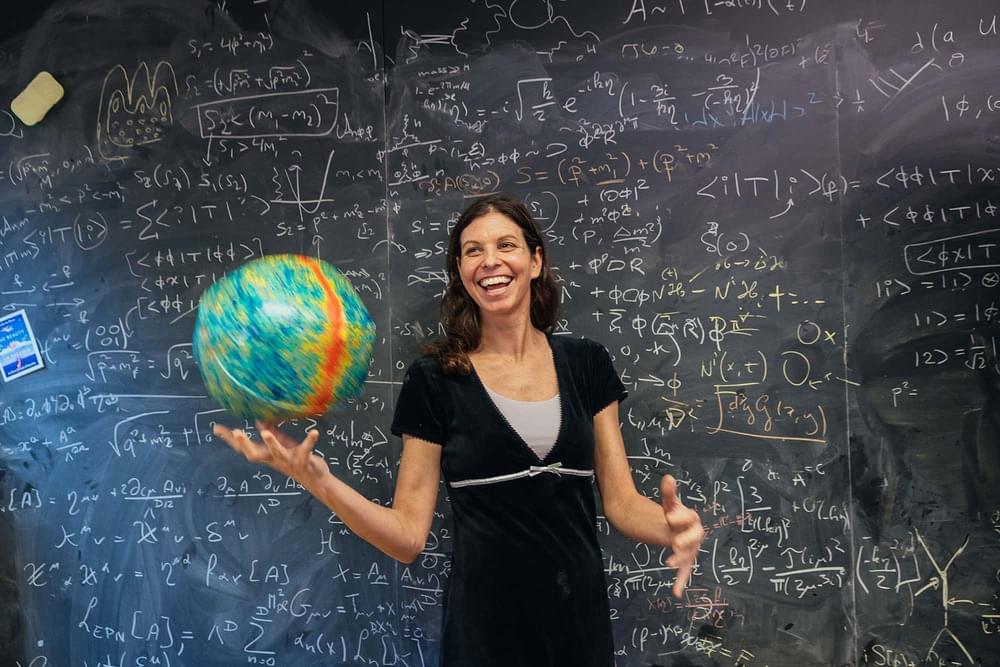

Claudia de Rham thinks that gravitons, hypothetical particles thought to carry gravity, have mass. If she’s right, we can expect to see “rainbows” in ripples in space-time.

Claudia de Rham thinks that gravitons, hypothetical particles thought to carry gravity, have mass. If she’s right, we can expect to see “rainbows” in ripples in space-time.

A very relevant subject for research.

The world appears to contain diverse kinds of objects and systems—planets, tornadoes, trees, ant colonies, and human persons, to name but a few—characterized by distinctive features and behaviors. This casual impression is deepened by the success of the special sciences, with their distinctive taxonomies and laws characterizing astronomical, meteorological, chemical, botanical, biological, and psychological processes, among others. But there’s a twist, for part of the success of the special sciences reflects an effective consensus that the features of the composed entities they treat do not “float free” of features and configurations of their components, but are rather in some way(s) dependent on them.

Consider, for example, a tornado. At any moment, a tornado depends for its existence on dust and debris, and ultimately on whatever micro-entities compose it; and its properties and behaviors likewise depend, one way or another, on the properties and interacting behaviors of its fundamental components. Yet the tornado’s identity does not depend on any specific composing micro-entity or configuration, and its features and behaviors appear to differ in kind from those of its most basic constituents, as is reflected in the fact that one can have a rather good understanding of how tornadoes work while being entirely ignorant of particle physics.

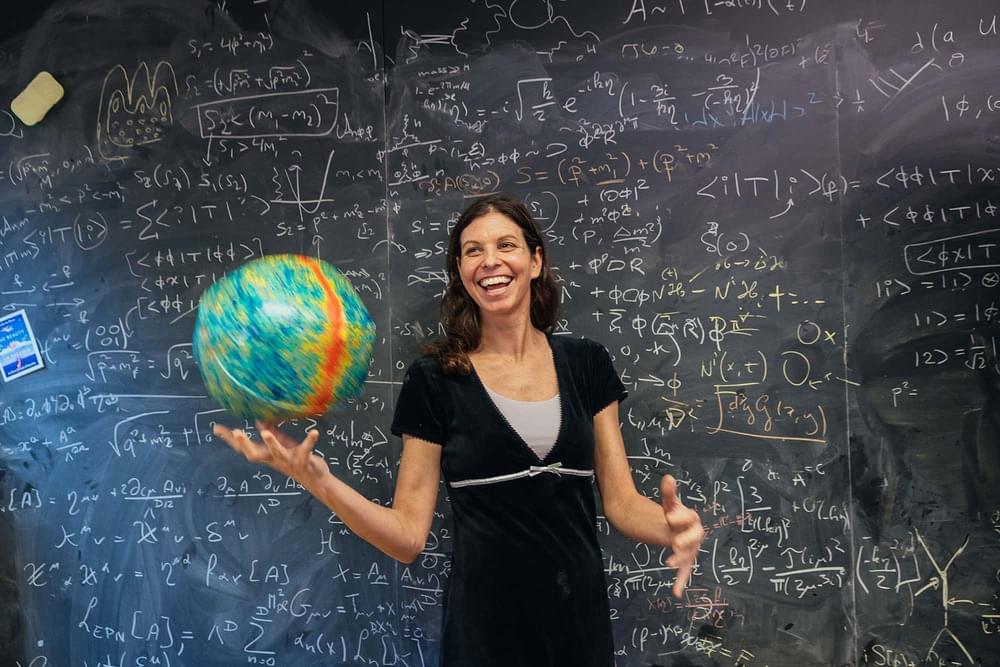

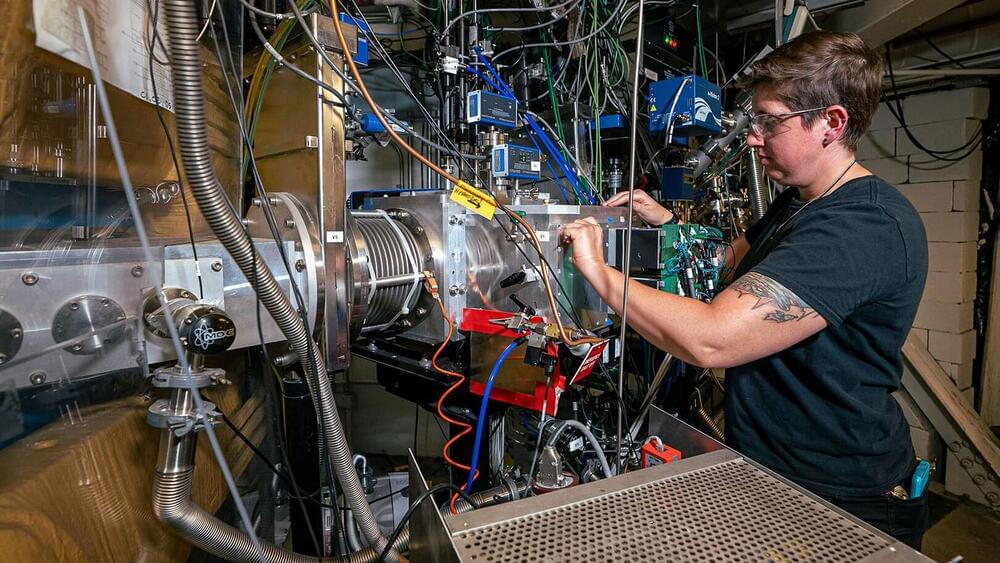

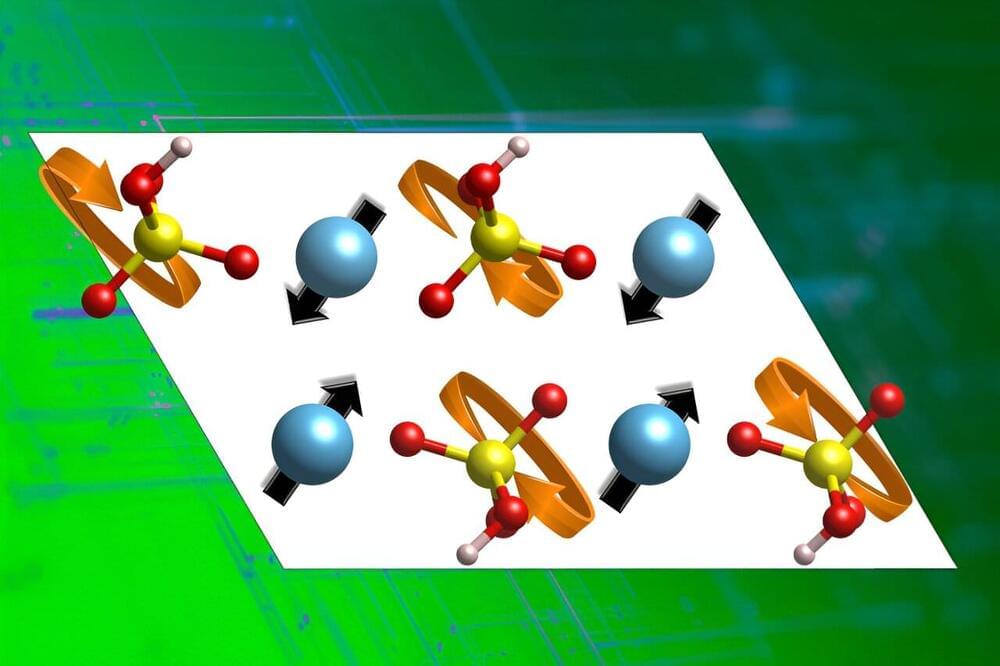

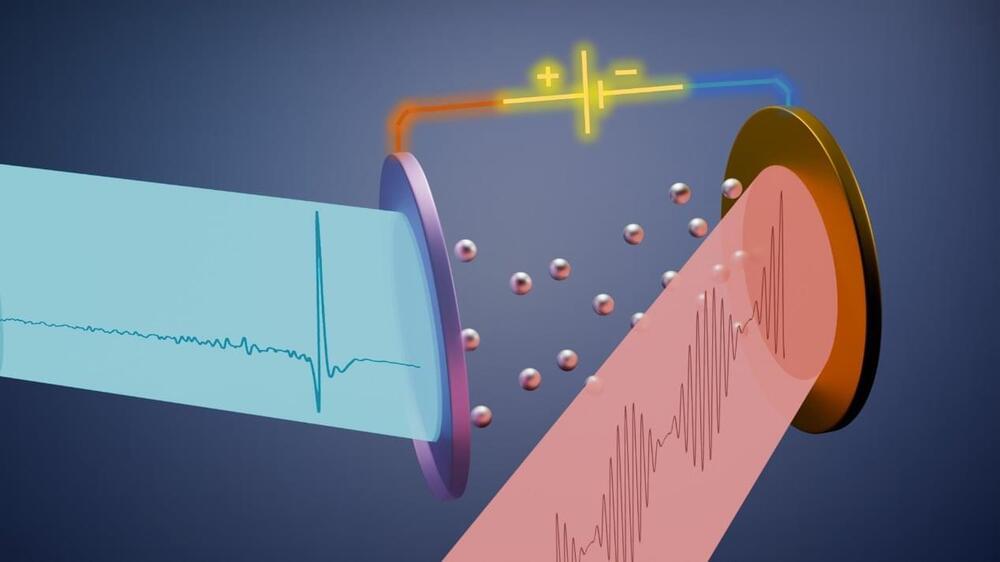

As the name suggests, most electronic devices today work through the movement of electrons. But materials that can efficiently conduct protons—the nucleus of the hydrogen atom—could be key to a number of important technologies for combating global climate change.

Most proton-conducting inorganic materials available now require undesirably high temperatures to achieve sufficiently high conductivity. However, lower-temperature alternatives could enable a variety of technologies, such as more efficient and durable fuel cells to produce clean electricity from hydrogen, electrolyzers to make clean fuels such as hydrogen for transportation, solid-state proton batteries, and even new kinds of computing devices based on iono-electronic effects.

In order to advance the development of proton conductors, MIT engineers have identified certain traits of materials that give rise to fast proton conduction. Using those traits quantitatively, the team identified a half-dozen new candidates that show promise as fast proton conductors. Simulations suggest these candidates will perform far better than existing materials, although they still need to be conformed experimentally. In addition to uncovering potential new materials, the research also provides a deeper understanding at the atomic level of how such materials work.

Quantum field theory (QFT) was a crucial step in our understanding of the fundamental nature of the Universe. In its current form, however, it is poorly suited for describing composite particles, made up of multiple interacting elementary particles. Today, QFT for hadrons has been largely replaced with quantum chromodynamics, but this new framework still leaves many gaps in our understanding, particularly surrounding the nature of strong nuclear force and the origins of dark matter and dark energy. Through a new algebraic formulation of QFT, Dr Abdulaziz Alhaidari at the Saudi Center for Theoretical Physics hopes that these issues could finally be addressed.

The emergence of quantum field theory (QFT) was one of the most important developments in modern physics. By combining the theories of special relativity, quantum mechanics, and the interaction of matter via classical field equations, it provides robust explanations for many fundamental phenomena, including interactions between charged particles via the exchange of photons.

Still, QFT in its current form is far from flawless. Among its limitations is its inability to produce a precise description of composite particles such as hadrons, which are made up of multiple interacting elementary particles that are confined (cannot be observed in isolation). Since these particles possess an internal structure, the nature of these interactions becomes far more difficult to define mathematically, stretching the descriptive abilities of QFT beyond its limits.

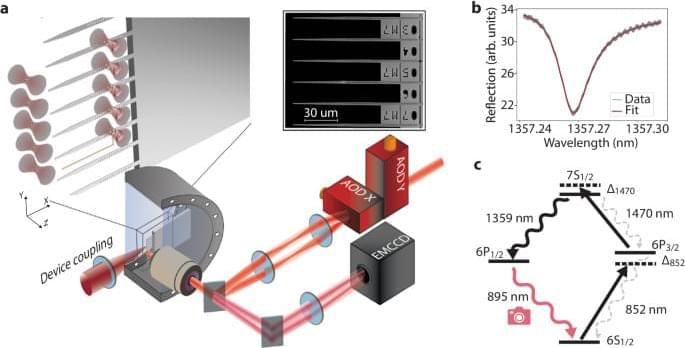

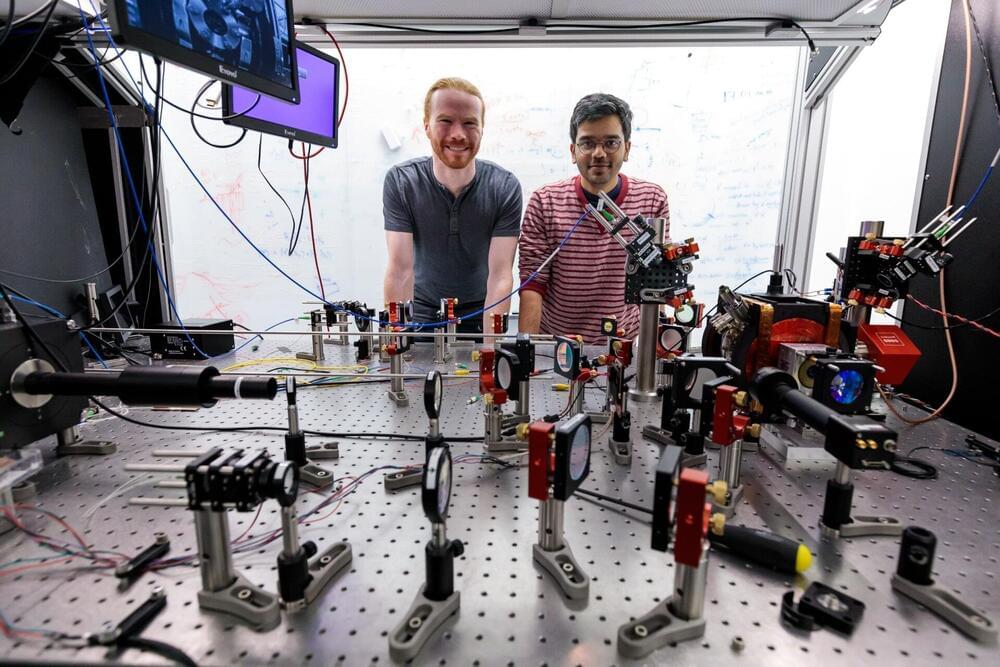

Quantum information systems offer faster, more powerful computing methods than standard computers to help solve many of the world’s toughest problems. Yet fulfilling this ultimate promise will require bigger and more interconnected quantum computers than scientists have yet built. Scaling quantum systems up to larger sizes, and connecting multiple systems, has proved challenging.

Twisting the graphene sheets in a bilayer stack, so that the 2D orientations of the sheets are offset from one another, can drastically affect how the stack reacts to light. Researchers have observed the effect experimentally, but they lack an accurate theory of the behavior. Now Lorenzo Cavicchi at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Italy and collaborators have developed a theory that predicts that light-impinged twisted graphene bilayers could host two kinds of electron oscillations known as plasmons [1]. One of these plasmons, the acoustic plasmon, is tightly confined between the two graphene layers, giving it properties that could allow for its use in studying light–matter interactions.

The electrons in a twisted graphene bilayer are distributed unevenly across the system. This inhomogeneous distribution results from the system’s misaligned carbon atoms. Cavicchi and his colleagues accounted for the electron inhomogeneity in their theory. They also modeled the bilayer as two distinct sheets rather than as a single unit, as was done previously.

The team’s theory predicts the bilayer can host two kinds of plasmon oscillations: the previously known optical plasmon, where all electrons move in the same direction at the same time, and an acoustic plasmon, where the electrons in each sheet move in opposite directions. For a graphene bilayer with a 5° twist angle between the sheets, the researchers predict that the acoustic plasmon should have a velocity of about 840,000 meters per second. That velocity is slow enough that the oscillations are confined within the 0.3-nm gap between the graphene sheets. The researchers say that this tight confinement leads to interactions between the plasmon and incoming light that enhance the intensity of that incoming light. This behavior could be useful for applications in quantum cavities.

New research explores the Cherenkov effect where superluminal speeds generate radiation and discusses new research using this principle to create terahertz radiation for advanced imaging and radar applications.

When charged particles travel through a medium at a speed greater than the phase speed of light in that medium (a phenomenon known as superluminal speed), they emit radiation. The resulting radiation forms a conical pattern. This phenomenon, known as the Cherenkov effect, has numerous fundamental and practical applications. The explanation of this effect earned the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1958.

The oblique incidence of light on the interface between two media is a similar phenomenon; in this case, a wave of secondary radiation sources is formed along the interface, which propagates at a speed exceeding the phase speed of light. The refraction and reflection of light from an interface is the result of the addition of the amplitudes of waves from all sources formed during light incidence.